There’s a famous adage: “Comedy is tragedy plus time.” Jewish comedian Jeff Ross takes that maxim literally in his Broadway debut solo show, “Take a Banana for the Ride,” now running at the Nederlander Theatre through Sept. 28. The one-man show weaves together his personal story of unrelenting loss with the humor that has long defined his career.

Best known as the “Roastmaster General,” Ross has spent decades turning celebrity insult comedy into an art form. His Comedy Central roasts became cultural events, and in 2024, he roasted Tom Brady so hard it became Netflix’s most-watched live broadcast. Part of his appeal is that he’s got the charm of a teddy bear with claws that leave a mark.

But “Banana” reveals a different Jeff Ross. Or rather, it peels back the layers to show not solely the version people think they know.

I’ll admit: my expectations were low walking into the theater. It sounded like a gimmick for a stand-up set dressed up with Broadway marketing. Fun, sure. Groundbreaking? Probably not.

But I was wrong. “Take a Banana for the Ride” isn’t just a comedy show. It’s 80 minutes of tightly-crafted transformation that earns its Broadway spectacle. Ross offers a raw meditation on love, loss, and the resilience that comes with surviving more than your share of tsuris. What emerges is deeply moving, surprisingly tender, and yes, very funny.

This is a show with a surprising amount of heart and chutzpah. It’s about family, grief, survival, and loss — including the loss of his hair from alopecia. Years ago, Ross mysteriously lost all of it, save for a thin mustache. He doesn’t shy away from roasting himself as a “blow-up Jeff Bezos.”

“Take a Banana for the Ride” is full of heart, humor, and loss

At its core, “Banana” is a story of triumph over trauma, and of being unapologetically Jewish.

“My real last name is Lipshultz,” Ross says. “That’s an old Hebrew word that means, ‘Hey, you oughta change that.’” (Ross is his middle name.)

Related post: Jewish comedians to watch

Not really a spoiler, but almost everyone Ross talks about in the show is dead, except for his younger sister.

His mother, Marsha, died of leukemia when he was 14. Five years later, his father passed away while Ross attended Boston University. More recently, he lost his three closest comedy friends — Norm Macdonald, and Jewish comedians Bob Saget and Gilbert Gottfried — within months of each other. Their deaths, he says, pushed him to move forward with the show. During the pandemic, he adopted two sickly rescue German shepherds and one of them died too. The other joins him onstage by the finale.

Death almost came for him, too, when he received his cancer diagnosis. Doctors found a stage-three tumor in his colon. Ross needed six months of chemotherapy and had seven inches of his colon removed. “I now have a semi-colon,” he quips. Now, by sheer miracle, he’s on Broadway.

So, yes, this show is very up-to-date with the timeline of his life.

As Ross told Jimmy Kimmel, “If you like ‘Annie,’ you’ll like my show because I play the bald guy and the orphan.”

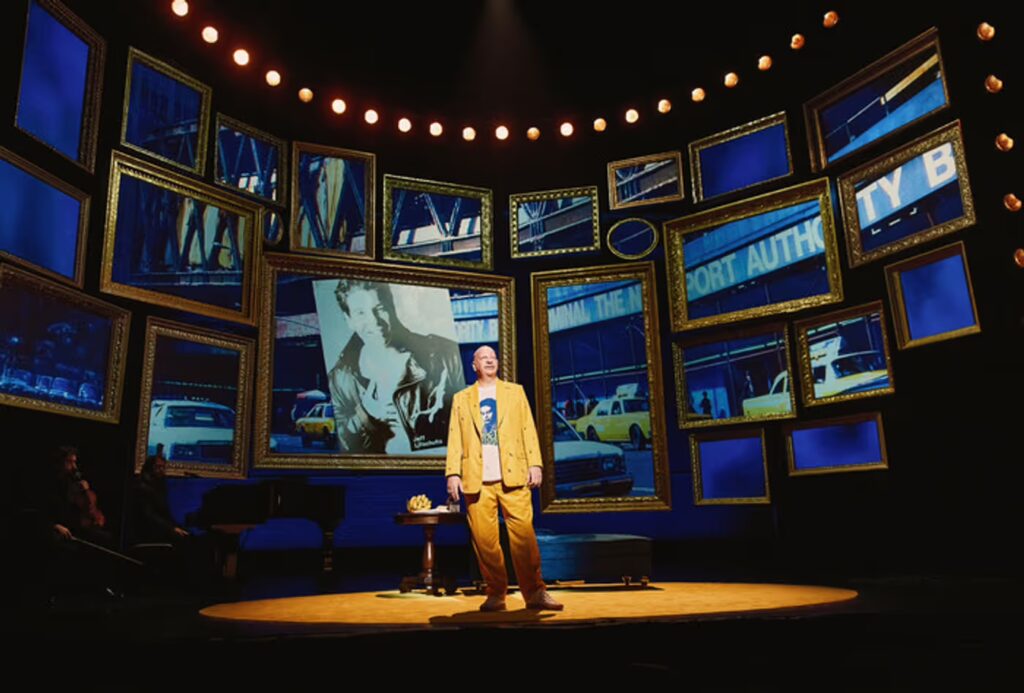

Projecting his past

The production itself is a sensory feast. More than a dozen screens arranged like picture frames project home movies and family photos, transforming the stage into a living scrapbook. Through Ross’s intimate storytelling, you really feel immersed in his personal history and develop an emotional attachment to the family members he remembers.

Early in the show, he recalls his Jewish upbringing in New Jersey, where his family owned a popular catering hall in Newark. He also performs a riotous musical number about all the things Jews invented, including Hollywood, kugel, penicillin, and more. It crescendos with the chorus, “Don’t F— With the Jews,” a genuine showstopper, choreographed with karate kicks, punches, and nunchuck spins. In a later verse, it becomes a full-blown sing-along, with a bouncing ball on the screens, encouraging the crowd to yell back the lyrics.

The karate moves also serve a deeper narrative thread, as Ross shares that he became the youngest black belt in the United States at 10 years old.

His writing and delivery are meticulous, which starts to make sense when you learn he’s been writing “Take a Banana for the Ride” for 30 years.

“I learned early on that comedy wasn’t just in my blood,” he says. “It’s my superpower. And this is my origin story.”

The result is cathartic, making strangers in the audience feel a deep connection to Ross and a little less alone.

Why “Take a Banana for the Ride?”

In the third act, the meaning behind the title takes shape. After college, Ross lived with his grandfather, “ Pop Jack,” while schlepping to open mics in New York City. Jack’s daily send-off was always the same: “Take a banana for the ride.”

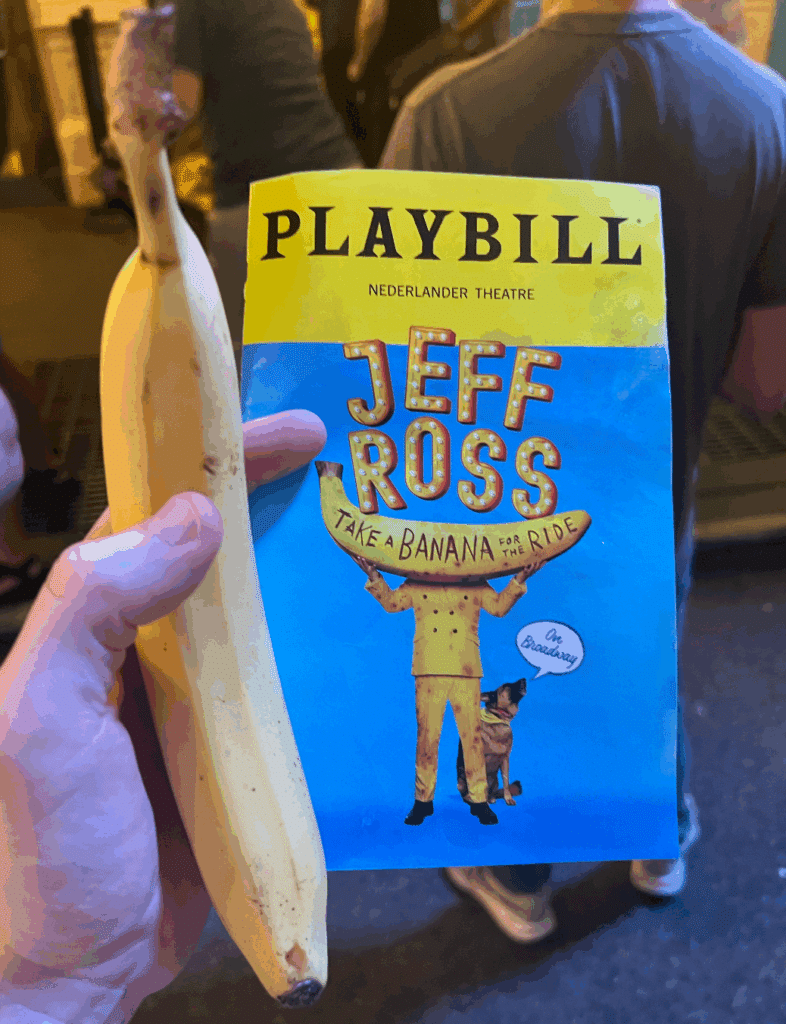

By the finale, Ross comes out into the aisle and invites anyone who has overcome hardship to stand up and share their story. Each person receives a banana for doing that and promptly gets roasted. In that moment, the metaphor lands. “Banana” is a reminder that grief and humor can share the same stage. And that sometimes, when life hands you cancer, dead parents, dead friends, a dead dog, and a world that keeps trying to break you, the best thing to do is exactly what Ross’s grandfather told him: take a banana for the ride. (or whatever the metaphorical equivalent of resilience is for you.)

As Ross notes about bananas, “the more bruised they get, the sweeter they become.”

And yes, I left with a banana after the show.

Originally Published Sep 7, 2025 10:47AM EDT