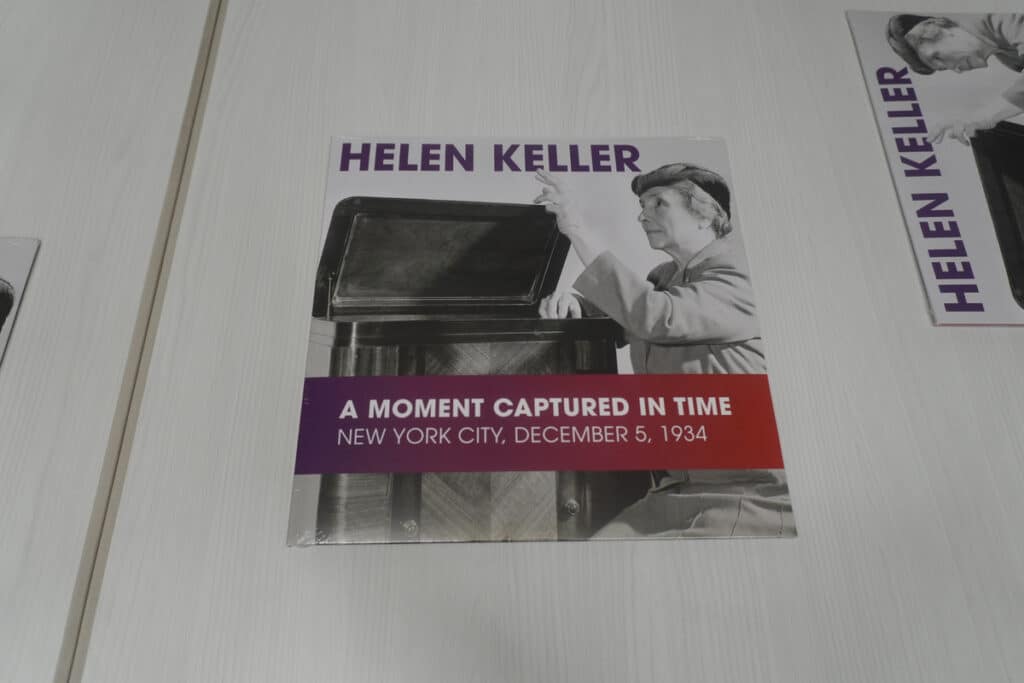

A voice from the past stirred hearts and minds on March 17, as an audio recording of Helen Keller — lost for decades — was played at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan. The recording, dated December 5, 1934, had been sealed in a time capsule and only recently unearthed.

Keller, who lost her sight and hearing at 19 months old after a severe illness, would go on to become one of the most influential authors, lecturers, and disability rights advocates of the 20th century. While her voice in the recording was faint, her message was clear — one of light in the midst of darkness. A staff member repeated her words aloud for the audience, bringing her sentiments to life.

A hidden treasure

Walter Decker, former executive vice president of the American Foundation for the Blind, explained that about 28 years ago, his head of maintenance found the time capsule on a Friday afternoon, but informed him it was wrapped in asbestos. He said Keller’s office had been in the same building they were meeting at the Center for Jewish History on 15 West 16th Street.

“It was very powerful,” Decker told Unpacked after hearing the recording. “I was working in this building 20 years after she died, so I felt a connection, and it wasn’t like someone from the distant past. We all knew of her. People had no idea she was an activist.”

AFP archivist Justin Gardner said he knew the recording was a one-of-a-kind and records show a transcript of a larger speech Keller was slated to give. Instead, she gave a shorter and more personal message. shorter message.

Eric Bridges, President and CEO of the American Foundation for the Blind said he was moved by the recording.

“It brought me to tears,” Bridges told Unpacked. “I had no idea there was any recording of her speaking. It was quite something.”

A letter to Hitler?

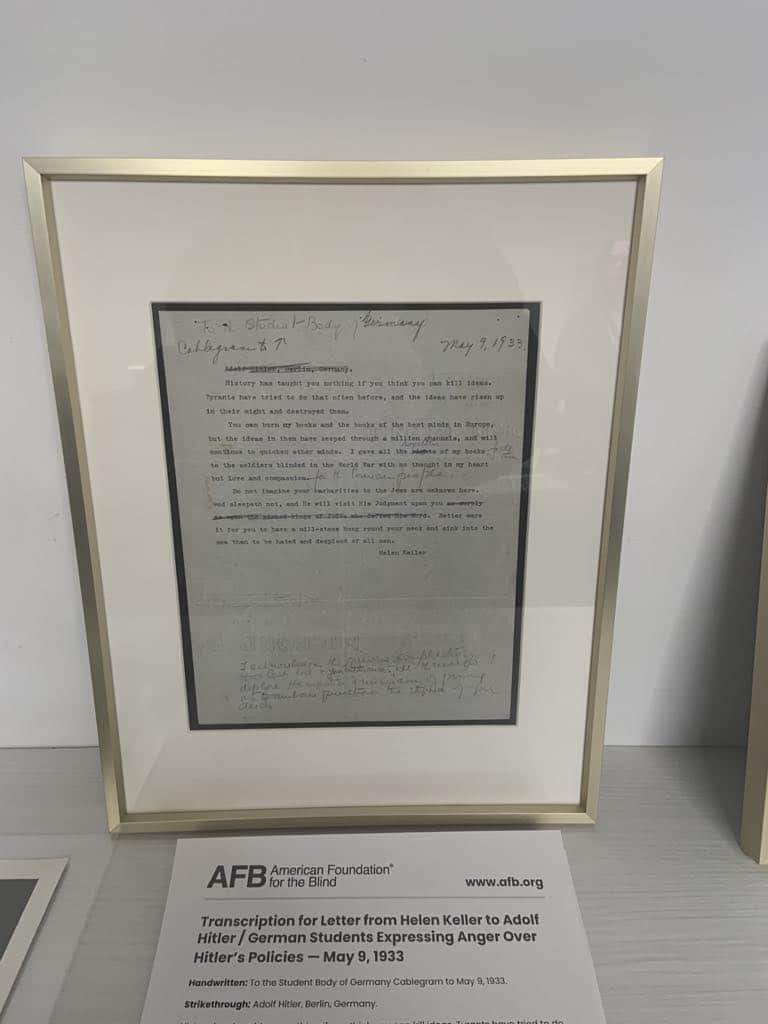

One of the most powerful moments of the event came when Sonya Shiflet, Chief Operating Officer of the AFB, presented a framed facsimile of a draft letter Keller typed on May 9, 1933. Originally addressed to Adolf Hitler, the name “Hitler” was scratched out and replaced with “German students,” indicating it may have been intended as an open letter. It was also published in the New York Times.

Gavriel Rosenfeld, President of the Center for Jewish History, accepted the letter on behalf of the institution. In it, Keller delivered a blistering rebuke of fascism and antisemitism:

“History has taught you nothing if you think you can kill ideas,” the letter from Keller read. “Tyrants have tried to do that often before, and the ideas have risen up in might and destroyed them. You can burn my books and the books of the best minds in Europe, but the ideas in them have seeped through a million channels and will continue to quicken other minds…Do not imagine your barbarities to the Jews are unknown here. God sleepeth, and He will visit his judgment upon you.”

Rosenfeld noted that Keller’s books were among those burned by the Nazis. He emphasized that the regime murdered more than 70,000 people with mental or physical disabilities. “Anyone who didn’t fit their model of Aryan physical supremacy was erased,” he said. “Everyone should have a voice and contribute to humanity.”

Rosenfeld reflected on the emotional impact of hearing Keller’s voice nearly a century later.

“The whole concept of a time capsule collapses time and space in such a profound way,” he told Unpacked. “It’s emotionally resonant because we’re hearing a message meant for us, years, even decades later, without the distractions of modern media. There’s no scrolling or swiping, just the human voice. You go deeper. It hits harder.”

“The whole genre of a time capsule whereby somebody is anticipating what will be thought of what they’re recording in that moment decades, if not longer, in the future, really collapses the distance of both time and space profoundly,” Rosenfeld said. “That was emotionally very resonant.

“On top of that, I was thinking that when we were listening to each of the recordings the recordings, how different it is from how we consume media today, in so far as there are so many distractions and hyperlinks and you see things on your phone and then you linger on them for ten seconds before you flit away to something else, and when you immerse yourself in the human voice and get deeper and deeper into what is being said, I think you take away more value.”

As the Center for Jewish History celebrates its 25th anniversary, Rosenfeld added that its mission remains not only to preserve the past but to activate it: “Our mission has always been to preserve Jewish History but then also to mobilize it to address present day challenges…whether it’s the cracking down on people who have fewer rights than others, or whether it’s things going on in the Middle East or antisemitism, we can’t figure any resolutions out unless we know what’s been tried in the past so historical insight is crucial.”

Helen Keller’s connection to the Jewish people

Keller’s relationship to the Jewish people was not merely symbolic. In 1952, she traveled to Israel, where she met blind and deaf Israelis and visited the homes of Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and then-Labor Minister Golda Meir. The 15-day trip left a lasting impression. Keller remarked that what she witnessed “fill[ed] my heart with faith in Israel’s prospects for future development.”

She also received the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies Award and has a namesake institution in Jerusalem: The Helen Keller School, founded in 1954 to serve visually impaired and learning-disabled children. Although now operated by the Franciscans, the school remains a testament to her enduring legacy in the Jewish state.

Helen Keller’s legacy

Keller was the first deafblind person to earn a college degree, graduating from Radcliffe (the women’s college of Harvard University) in 1904. She toured the country with a vaudeville show between 1920 and 1924, sharing her life story and answering audience questions with the help of her beloved teacher, Anne Sullivan.

Among her many accolades, Keller was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953. She is also remembered for one of the most striking quotes in modern history: “The only thing worse than being blind is having sight but no vision.”

Keller authored “The Story of My Life,” became world-renowned, and remains a beacon of courage, intellect, and compassion. Born on June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama, she passed away on June 1, 1968, in Connecticut.

Disinformation against Keller

Unfortunately, the program also addressed a disturbing trend: misinformation about Keller. A presentation showed podcast clips where speakers falsely claimed Keller was a myth, or that her achievements were exaggerated.

While some might pass it off as comedy or jealousy, experts at the event warned that the erosion of historical truth has real consequences.

Gardner, who oversaw the digitization of the fragile recording, said this time capsule was unlike any other he’d encountered.

“It was really interesting because I can’t think of a time capsule that has such a direct personal message of that real voice from the past,” he told Unpacked. ‘I said something about how we think of a time capsule, and there is an old newspaper and some old coins, but not an emotional and personal voice. It was such a specific message to us, besides the fact that it was in this building. I feel like a small part of something big.”