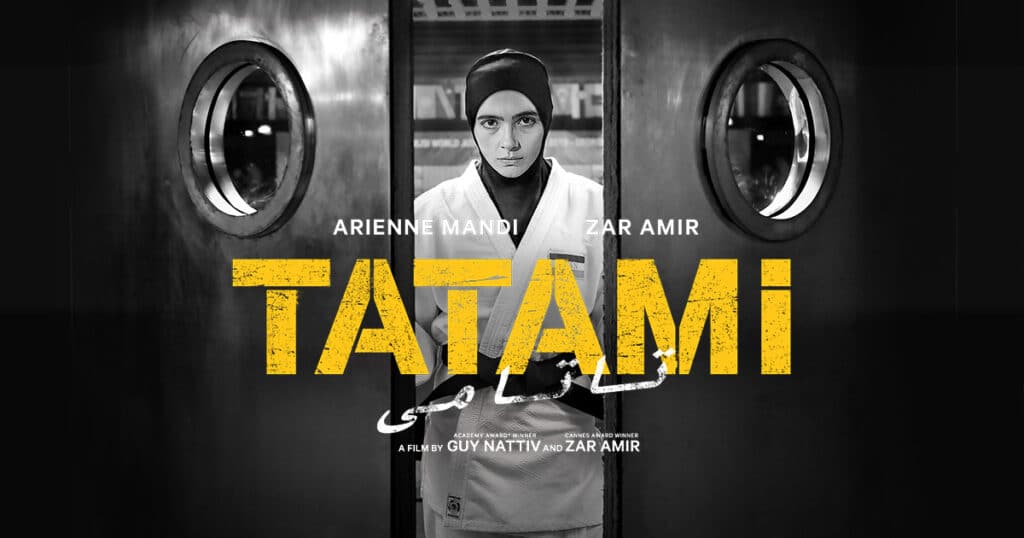

What were the chances that the New York premiere of “Tatami” — a tense drama about an Iranian judoka forced to choose between her Olympic dreams and her country’s ban on competing against Israelis — would fall on June 13, the very day open war broke out between Israel and Iran?

In an ideal world, sports would transcend politics. But in reality, the two are often deeply intertwined. “Tatami” is a gripping, expertly crafted film that explores this intersection with nuance and emotional intensity. Thanks to a few bold, unexpected creative choices, it doesn’t just tell a powerful story — it elevates it from compelling to unforgettable.

Conflict of country vs. athlete

Arienne Mandi delivers a powerful performance as Leila Hosseini, Iran’s best hope at the World Judo Championships, held in Georgia. A rising star in the sport, Leila dominates on the mat, expertly taking down international opponents with skill and precision. But just as her path to the finals seems clear, politics intrudes.

After a string of victories, her coach, Maryam Ghanbari (played with quiet intensity by co-director and actress Zahra Amir Ebrahimi), pulls her aside with chilling instructions: Leila must fake an injury and withdraw. The reason? There’s a possibility she’ll be matched against an Israeli judoka in the upcoming rounds — and Iran, which does not recognize Israel, forbids its athletes from competing against “the Zionist entity.”

A legend or a lie?

Leila, furious, confronts Maryam. The tension crackles between the two women, who share a complex bond shaped by trust, ambition, and state control. Maryam was once a competitor herself, but her career ended abruptly due to an alleged injury. Now, Leila begins to question that story: Did Maryam truly get hurt, or did she, too, sacrifice her career for political obedience? Was her downfall a tragic accident — or a warning masked as mentorship?

As their argument escalates, the lines blur between duty and self-preservation, legacy and betrayal. The question remains: is Maryam protecting Leila, or repeating the same cycle of silencing and surrender?

“Tatami” tackles female rage and the need for empowerment

One of the film’s most haunting moments comes when Leila, in a fit of desperation, slams her head into a mirror. Blood drips down her face as she stares into her fractured reflection. Is she inflicting injury to create a believable reason to withdraw from competition? Or is this a visceral metaphor: that in a society where women are expected to train, to excel, and to represent their country, they are simultaneously denied autonomy, forced to shatter their own identities with a single political command?

In this scene, Leila screams, but no sound escapes. The silence is deafening. It echoes the reality of countless individuals silenced by authoritarian regimes, their pain and resistance rendered invisible to the outside world. While rooted in the specific context of Iran, the moment transcends borders. It speaks to anyone trapped in an oppressive system — whether political, cultural, or personal — where one’s voice, body, and dreams are not their own.

Focus on women in sports

“Tatami” arrives at a moment of heightened attention toward women in sports. The WNBA, long underappreciated, is finally enjoying a surge in visibility thanks to breakout stars like Caitlin Clark. Yet even with growing viewership, the conversation around gender inequity — especially in pay and media coverage — remains a national talking point. Within this landscape, “Tatami” feels especially timely.

Sports films centered on women are still relatively rare. While shows like Netflix’s “Cobra Kai” have featured standout performances by Mary Mouser, Peyton List, and Oona O’Brien (playing fierce, high-kicking teen fighters), and Hilary Swank once headlined “The Next Karate Kid in 1994,” female-driven stories in combat sports remain the exception. Even “Tehran,” the Apple TV+ spy thriller starring Niv Sultan as an Israeli Mossad agent, trades in adrenaline and action, but not in the context of sanctioned sport.

Judo, the centerpiece of “Tatami,” may be unfamiliar to many viewers, including me. As someone more versed in boxing and UFC, I came into this film knowing little about terms like “Uchi Mata,” a powerful inner thigh throw that Leila executes flawlessly in the early rounds. But even without prior knowledge, the film communicates the physicality, strategy, and emotional stakes of the sport with clarity and force.

As Leila’s victories mount, so does the pressure. The tension between her and Coach Maryam explodes as Leila begins to suspect that the plan to fake an injury wasn’t a last-minute decision but something orchestrated from the start. Their bond, built on years of training and shared national pride, teeters on collapse. At one point, the two nearly come to physical blows, their argument charged with betrayal, frustration, and a devastating realization: in a system like theirs, even success can be weaponized.

Fight scenes

The judo sequences in “Tatami” are executed with striking precision: visceral, tense, and cinematic without losing the authenticity of the sport. But just as gripping are the internal battles Leila fights: the psychological tug-of-war between duty and desire, fear and defiance. Her confrontations with Coach Maryam are especially potent, charged with layered emotion and decades of unspoken expectations.

One flashback offers a revealing glimpse into Leila’s personal life. She argues with her husband, Naser (played by Ash Goldeh), after he becomes visibly agitated during a phone call with a government official. The call, disturbingly routine in context, demands that he provide written permission for his wife to leave Iran and compete in Georgia. While the scene underscores the bureaucratic control exerted over women in Iran, it falls a bit flat in execution, lacking the nuance that might have made Naser’s reaction more believable. Given the reality of life under Iran’s restrictive laws, it seems unlikely that this requirement would come as a surprise to either of them, especially him.

Black and white

Some filmmakers rely on black-and-white cinematography as a stylistic crutch when substance is lacking, but “Tatami” is not one of those films. The choice here is deliberate and impactful. Israeli director Guy Nattiv, who previously used stark monochrome effectively in his film “Golda,” applies it again with precision and purpose. Known for his Oscar-winning short “Skin,” a searing look at white supremacy in the United States, Nattiv brings his signature intensity to “Tatami,” co-directing first-time filmmaker Zahra Amir Ebrahimi.

Together, the pair make history: “Tatami” is the first feature co-directed by an Israeli and an Iranian. The collaboration alone is powerful, but the result is even more so — a taut, visually arresting film that draws strength from its contrasts, both literal and metaphorical.

“Tatami” brings top-notch acting to the forefront

Arienne Mandi delivers a career-defining performance as Leila, embodying strength that is both physical and emotional. She’s a fighter — not just on the mat, but in the face of systemic oppression — and Mandi captures that duality with remarkable restraint. She doesn’t need bulging muscles or melodrama to convey power. Instead, she radiates quiet intensity, letting her silences speak volumes. In some scenes, she goes straight for the jugular; in others, she simmers with tightly contained rage or grief. The film’s sparse dialogue works in its favor: sharp, purposeful, and refreshingly un-preachy.

Leila never positions herself as a martyr or a symbol. She’s not trying to change the system; she just wants the right to compete on her own terms. Her stance is simple yet revolutionary: she wants to keep fighting until an opponent beats her, not surrender because politics tell her to. In a smaller but pivotal role, Jamie Ray Newman brings a grounded presence as Stacey Travis, an observant World Judo Association official who notices the tension between Leila and Maryam and starts asking questions. Her character is a reminder that, sometimes, all it takes to spark change is someone willing to pay attention.

Some viewers may be surprised at the limited screen time given to Shani Lavi, Leila’s potential Israeli opponent, portrayed by Lir Katz. In another kind of sports drama, Shani might have served as a central foil or even a symbolic “rival.” But “Tatami” wisely resists that temptation. The film isn’t about a clash between two athletes from opposing nations, but about one woman’s battle against an oppressive regime, the system that controls her, and the coach who enforces it. The opponents she faces on the mat are almost secondary. The real fight is internal and existential.

Fictional film, real-world roots

Though “Tatami” is a work of fiction, its inspiration is drawn directly from real-world events. Iran has long forbidden its athletes from competing against Israelis, forcing them to withdraw from matches or fake injuries. One of the most notable examples was Saeid Mollaei, a top-ranked judoka who, in 2019, was pressured to throw his semi-final match against Belgium’s Matthias Casse to avoid potentially facing Israeli champion Sagi Muki in the final. Disillusioned, Mollaei defected and sought asylum in Germany. His defiance made headlines and made him a target.

As a result of this and similar incidents, the International Judo Federation banned Iran from competition in 2019, though the ban was lifted in 2023. Similar controversies have emerged in other countries: at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, Algerian judoka Fethi Nourine withdrew from a match to avoid facing Israel’s Tohar Butbul. “Tatami,” unsurprisingly, has reportedly been banned in Iran.

Could “Tatami” win an Oscar?

The film’s title, “Tatami,” refers to the woven mat that judoka train and compete on, but the symbolism runs deeper. These mats absorb blows, support fighters, and yet they’re also the surface on which athletes are stepped on, pushed down, and sometimes sacrificed for national agendas. The metaphor couldn’t be more apt.

“Tatami” is easily one of the standout films of 2025 so far. Arienne Mandi should be firmly in the conversation for Best Actress, while Nattiv and Ebrahimi deserve serious consideration for Best Director. Amir also merits attention for her nuanced supporting role. The film’s message about bodily autonomy, national loyalty, and the right to simply exist as an athlete is both timely and timeless.

Even if you don’t typically gravitate toward sports films or political dramas, “Tatami” transcends both genres. It’s not just about judo. It’s about the courage to stand your ground, even when the ground itself feels like it’s been pulled out from under you.