Yael: From Unpacked, this is Jewish History Nerds, the podcast where we nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history. I’m Yael Steiner.

Schwab: And I’m Jonathan Schwab. And Yael, we’re well into our fourth season, focusing on objects and symbols. Today, you’re going to be telling me a story, and I’m really excited to hear what you have.

Yael: Sometimes when I’m preparing for these episodes, I realize what a gigantic nerd I actually am and how absolutely perfect this gig is for me and how grateful I am for it because I just had such a good time reading the sources for this week’s episode. And I always do, I think, but something about this week’s journey and the artifacts that we’re going to be talking about just really jumped off the page and I’m really excited to share it with you.

Schwab: Wow, great. I’m so curious to hear what captivated your attention.

Yael: Unlike what I normally do, which is take a really, really long time to get to what the topic actually is, I’m gonna jump in right now. We’re going to be talking about two very, very, very tiny silver scrolls, silver amulets.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: that were discovered in 1979 in Ketef Hinnom in southwest Jerusalem, right outside the Old City, that are known to us presently to be the oldest evidence of Biblical scripture.

Schwab: Cool. I feel like this fits in nicely with some of the things we’ve been talking about this season.

Yael: Yes, so when we talked about the the magic bowls, that was the oldest evidence of Talmudic and Babylonian writing that we have. And this is actually the oldest evidence of canonical Biblical writing. The text that we’re going to be talking about is from Numbers, from Bamidbar and is fairly well known. It is the text of Birkat Kohanim, the priestly blessing, which you may or probably are familiar with. Are you a priest by any chance?

Schwab: I am not, no, I’m not of the priestly persuasion, I’ve heard it recited and our family does have the custom to bless our children using these verses every Friday night, which I did not grow up with in my family, but we started doing with our own kids. And now…

Yael: of the Priestley cast.

Schwab: because they’re very into it and I guess feel it’s unfair they also insist upon putting their hands on our heads and also doing the same thing. everybody, yeah, everybody gets blessed all around.

Yael: That’s adorable. That’s really sweet.Schwab: so now, I don’t know, this thing that I do every week, I’d love to learn more about the history of it. So it sounds like this is a very, very old evidence of these verses.

Yael: Yes, we are going back to the sixth and seventh century BCE, though I will say one thing that I discovered while doing the research here is that archaeologists do not agree with each other. So the scholarly consensus or mostly consensus is that these are from the first temple period, though there are others who have tried to

Schwab: so very old. Yeah. Mm-hmm.

Yael: say they’re from the Hellenistic period, which is a few, several centuries later. Either way, they predate the Dead Sea Scrolls, which…

Schwab: I was gonna say, when we think of the oldest text of the Bible, it’s the Dead Sea Scrolls

Yael: So, yeah, so these are approximately five, six, 700 years older than the Dead Sea Scrolls, which is pretty, pretty insane.

Schwab:

Which is a lot, y

Mm-hmm. Before we continue with the story, I do want to say that I appreciate that you brought up the blessing of your children and apparently their blessing of you on Friday night with this priestly benediction that comes from the sixth chapter of Numbers of Bamidbar, because Gabriel Barcai, who is the archaeologist who headed up the dig that led to the discovery of these scrolls in Southwest Jerusalem says that they are actually the first words of Hebrew that he remembers because they come back to him from Friday nights when his father would bless him as a child, which I thought was really poignant and beautiful. So like they’re not just random verses. I think the most famous Bible verse is probably Shema Yisrael, but then like this is, I don’t know, not too far behind.

For those of you who maybe are not familiar with the Hebrew words, but maybe have attended synagogue or seen clips of services, you might be familiar with the part of services where certain people go up in front of the Ark and then spread their fingers out like Mr. Spock from Star Trek, bless the congregation. They kind of go like this. For those of you who can see me on video, I’m spreading out my hands into two groups of two fingers and then my thumb. Leonard Nimoy, the actor who played Mr. Spock on Star Trek, yes. No, yeah.

Schwab: got it from this, right? Like it’s not incidental. He’s Jewish. And I’ve heard this story of like maybe he, maybe his family are also priests or like he, they were looking for some sort of thing. And he’s like, I know this, this like Jewish symbol thing that people do.

Yael: you know, it goes along with that catchphrase from Star Trek, live long and prosper, which, you know, could very well be a quick summary of what the priestly benediction actually is.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. That’s so funny. I had never thought of that before. But right, it is a form of blessing. Like it’s a form of greeting and blessing.

Yael: It’s a catch-all blessing, the live long and prosper of blessings in that God is promising to protect you and to have his countenance upon you, his shechinah, in Hebrew, and that that is basically him saying, whatever it is you want for yourself, that is what I am going to bring to you. It is not a blessing for rain. It’s not a blessing for a harvest. It’s not a blessing for a child.

But this is not about Star Trek. This is about the discovery of these two silver amulets in Ketef Hinnom on the southwest corner of Jerusalem. Just to situate us, for those of you who are familiar with Jerusalem, this is at the edge of

a road called Zarech Beit Lechem, which means literally the path to Bethlehem. It’s outside the Old City. It is down a hill from both the Old City and the center downtown of Jerusalem, Ben Yehuda, what’s called, like the Ben Yehuda area now. And it’s adjacent to the grounds of a Scottish church and also adjacent to what is now the Menachem Begin Heritage Center.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Okay. That’s helpful. TAnd that is where, that is the shoulder of Hinnom.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yes.

Yael: Ketef shoulder, because that is actually a description of the topological, the topography of Jerusalem, because the way that the ridge is shaped is sort of like a shoulder. And Hinnom is actually an area that’s mentioned in the Bible several times.

And it is also a reference, I don’t know if you’re familiar with the term Gehinnom. That is, ge is valley, that is the valley of Hinnom which was eventually squashed together for the word Gehinom or Gehenom, which is…

Schwab: Yes. Which is hell. Or H-E-L-L as my children would insist.

Yael: Yes. H-E double hockey sticks. So that is the site. The site that we are talking about was…

Schwab: So we dug, we found these silver amulets in hell, I’m hearing.

Yael: One of the most interesting things I heard while researching this podcast was from a Christian scholar named Dr. John Monson, who actually as an adolescent participated on the dig where these scrolls were found. And he was the child of missionaries who grew up in Jerusalem and he was a member of this Scottish church. And he said that, you know, there would be days when the members of the church would say, let’s go down into hell for our picnic because they would just go down into the valley and I don’t know if he meant literally that someone in English was saying let’s go down into hell or someone was saying let’s go down to gehenom, but it seemed to be something that the church members found very funny which I also kind of found charming.

Schwab: Yeah. Yeah, I feel like there’s probably so much to talk about of the significance of these and the age and dating them, but why were they digging there in the first place?

Yael: So, great question. So I don’t know if you recall, but in the episode about the magic bowls, I mentioned something called a Historiola. Historiola was when the text of the bowl would open with an anecdote about something that had happened in the past in order to lure the demon into the bowl and to scare it.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Now I remember this, yeah. Ooh. Mm-hmm.

Yael: So that’s what we’re gonna do here. I’m gonna lure you in with a bit of Historiola, and capture your attention. And I’m going to take you back to the 60s and 70s in Israel when archaeology was blossoming and a young archaeologist named Gabriel or Gabi Barkay. I’ve heard it mostly pronounced as Barkay, but Dr. John Monson, who claims in the lecture that I listened to, to have an avuncular relationship. He said that said that Barkay was like a an uncle to him. He pronounced it Bar-ka-ee

Schwab: And he’s an expert. Mm-hmm.

Yael: He has a PhD from Harvard, so let’s just go with that, So Barkay, was born in the ghetto in Budapest in 1944. He actually credits his life to Stalin. He says many people owe their death to Stalin. I owe my life to Stalin because right around the time he was born, shortly after the Red Army came in and liberated Budapest, I also have to say my grandparents owe their lives to Stalin. So he’s not the only one, but it is.

Schwab (34:11)

Whoa.

Mm-hmm.

Yael (34:24)

It is a weird position to be in. So he moves to Israel at the age of six and grows up in Jerusalem, I believe in the Rehavia area, and spent much time as a child walking around what was then a very open, not built up city. And the way he puts it, he sort of would muck around in open areas and find cool things and became really interested in archaeology and nagged his father for some books about archaeology. You know, was on this path from a very young age.

While he was doing his studies for his PhD, he realized that the studies of the old city of Jerusalem, particularly the city of David area,there was a lot of academic work being done about that area. Schwab: But if this is before 1967, was all of that even accessible?

Yael: So I believe it was right after 67. Monson, who grew up in Jerusalem, says that because he grew up there in the wake of the 67 war, he actually describes it a little bit like a Pax Romana of like this really idyllic time to be in Jerusalem, discovering new things. The way he describes it also was that there was just this melting pot of different people from different ethnicities and things seemed to be going quite well.

Schwab: Cool, yeah.

Yael: And I believe his father was a professor of some kind and that’s how he developed this deep relationship with Barkay. And so Barkay decided he didn’t want to step on anyone’s toes and he didn’t want anyone stepping on his toes. So instead of focusing his work on the city of David and inside the old city itself, he was going to do what he called extramural work.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Which meant outside the walls of Jerusalem. I personally had never before thought about what the word intramural means, but it means inside the walls, which makes sense. I love learning something new. That’s how nerdy I am. So he decides

Schwab: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense, right? A mural literally, right? Means wall. So he was like, okay, the excavations and archeological research on the temple is so overdone, everyone’s doing that. I’m gonna go dig in a spot where nobody’s digging.

Yael: Yeah, he called it para-urban and extramural.You know, but there must have been activity, you know, human living activity, cultural activity. And, you know, where did they bury the people? They must have buried the people on the outskirts of the city. And often burial sites are very informative to us about a society. Because as we know, it’s not only people that are buried, especially in ancient times, people were buried with a lot of their things.

Schwab: Right. Yeah. Mm-hmm. Boy. Now I’m a little worried about where these silver amulets came from.

Yael: Yes, they were found in a burial chamber. So Barkay undertakes an excavation in this area of Ketef Hinnom, Southwest Jerusalem. And, it’s going quite well. They find a lot of really interesting things, but he doesn’t have a lot of monetary support.

And what he does have is the support of pre-adolescent and adolescent boys from a local archaeology club. One of the teenage boys who helps him is Dr. John Monson, who was there when all of this happened. But Monson is not the lynchpin in this story. The lynchpin in this story is a young boy named Nathan, who I believe was 13 years old in 1979 and was driving Barkay crazy.

Barkay said that Nathan was always pulling on his shirt and I don’t know if he was asking him to explain things or asking for help or whatever it was, but you can picture the scenario.

Schwab: Yeah, like I’m imagining, right, just like a whole bunch of, I don’t know, adolescent boys doing some of the most important archaeological digging work that’s been done.

Yael: So we’ll get there. So Nathan’s driving Barkay crazy, and what Barkay decides to do is to send him into one of these burial chambers. They had these areas on the periphery of the rooms where there were like head indentations or pillows that sort of mirrored what people slept on in, in those times that they also used to lay out the dead bodies. And what they understood was that the bodies would be placed in these chambers with the heads on these little carved out pillowy things. The flesh would decay and then they would take the bones and they would bury the bones in a lower level of the chamber to make room for the new flesh that has to decay in the upper level.

Schwab: Now I understand why this place is referred to as hell. Like I’m just imagining there’s like a giant pit of bones.

Anyway.

Schwab: Barkay sends him into a burial chamber and says he wants him to sweep it out and clean it out. It had already been excavated. He wants him to sweep it so that it’s in pristine condition for photography. And he says, I want it so clean that you can lick it. I heard Barkay say this in an interview, so I’m not making it up.

So Nathan goes in there, he cleans it up. He does apparently a very good job, but as 13 year old boys are wont to do, he started playing around a bit when he got bored and he took a hammer and started banging on the floor, which is, you know, not something unanticipated when you have 12 and 13 year old boys mucking around in archaeological site. So I understand that he didn’t have financial backing, and that he was doing the best he could, but you know, this was all very foreseeable. What was not foreseeable was that when he broke the floor, the entire thing would cave in and a lower chamber would be discovered full of treasure.

Schwab: Whoa. And is Nathan okay? Okay, good.

Yael: Nathan, he’s okay. Nathan’s okay. He comes out of the chamber holding two jugs, chasing after Barkay, again pulling on his shirt. And Barkay is thinking, I’m going to suffocate this child. Those were the words that he used.

Schwab: Yeah, he’s like, I sent him to the burial chamber and he came out.

Yael: And then he turns around and he sees these, he’s holding these two jugs that are from the first temple periodthey all run over and they find this room filled with jewelry, ceramics, all sorts of crazy things. Ultimately, I believe they find the bones of 90 something people.

So Nathan in his mischief ends up doing us all a great service, a very happy accident. And when they realize that there is a tremendous amount of significance to what is found the 12 and 13 year olds are replaced by professional archeologists from universities.

Schwab: All of a sudden, there’s a lot of monetary backing. Yeah.

Yael: And they actually, keep it very quiet. They keep it very hush hush. I believe I read somewhere that the people working on it were not allowed to tell their spouses or their families what they were working on, because they felt if word had got out, there would be, you know, the equivalent of a gold rush or modern day grave robbers who would not only disturb the site for historical and academic purposes, but just steal things. So he said, they worked 24 hours a day. They were provided with electricity from St. Andrew’s Church, that Scottish church that we mentioned earlier. And at one point while they were doing this excavation, a woman named Judith Hadley, a professor at Villanova, who was a student at that point in time and in fact was a student of Dr. John Monson’s father.

Schwab: Hmm, this is the first time I’m hearing about this John Monson character.

Yael: You know how it is. I find a guy and I latch on. And it takes a while before I give it up. So Dr. John Monson So this woman, Judith Hadley, finds a very tiny, very, very tiny little thing that is purple, maybe this around the size of the filter of a cigarette. I don’t know what that translates to in vapes, so if you don’t know what a cigarette looks like, it’s very small and really small. she brings

Schwab: Yeah, really small, right? Like that’s where we’re talking about. I don’t know, for those non-smokers out there, the cap of a pen. Is that about the right?

Yael: Yeah, I don’t know. There are two amulets that we’re going to be talking about. We haven’t even gotten to them yet. The larger one is two centimeters long, rolled up. It’s a scroll that’s rolled up one centimeter in diameter. That’s rolled. So it’s a few centimeters larger than that unrolled, but still very, very tiny. The smaller one is half the size. So one centimeter long and a half a centimeter in diameter. So we’re talking about something really, really small.

Schwab: Yeah. Hmm. Two very small objects, yeah.

Yael: Which a lot of people may not have given a further look to, but this woman, Judith Hadley, did, and she brought it to Barkay, and he recognized it as corroded silver. And he had this hunch that there must be something written on the inside. There was significance to this. It wasn’t just a piece of crumpled silver.

Schwab: Because it’s like a scroll shape in silver. It’s the type of thing where someone would write something and then put it in a nice case.

Yael: The problem is this thing is tiny and this thing is old. And it prevents a real problem for archaeologists and excavators to study it and to look at it. And how do we

Scroll it, unroll it.

Schwab: Right, if you open it up, it’s gonna decompose immediately, sort of thing.

Yael: Exactly. So it was first sent to a university in Leeds in the UK. They refused to work with it. Then it was sent to a university in Germany. They refused to work with it. I think everyone was just afraid that they were going to be the ones to destroy it.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Right, if we open it and it falls apart…

Yael: Nobody wanted that responsibility. So ultimately it ends up back at the Israel Museum and it takes, I think, almost three years. Preservationists at the Israel Museum develop a method to try to unroll it. They dip it in an acid solution, or two, there are two of these amulets. One was found on site by Judith Hadley and another was found eventually through the sifting of all the other materials over time. They dip it in an acid solution and they coat it in some sort of acrylic polymer. And ultimately, millimeter by millimeter by millimeter over the course of months, they are able to unroll it.

Schwab: Wow. I’m just imagining that, like someone’s coming to work every day and like just slightly un-scrolling a little bit. Wow. Yeah.

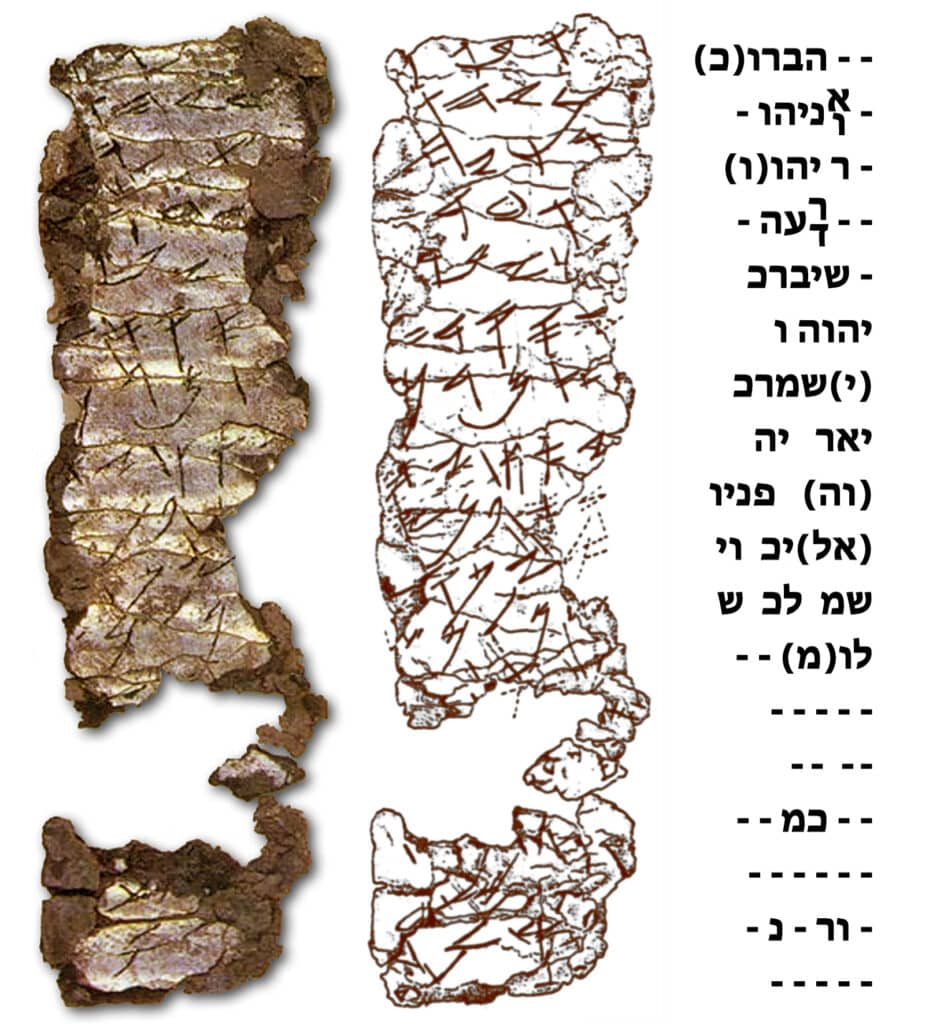

Yael: Kind of but before they did that actually they went through a bunch of trial and error processes including heating the silver which they thought would soften it and allow them to unroll the amulet and unfortunately they actually lost some material or some of the wording because of that so it just goes to show you that this isn’t this is really not simple and you can have the best intentions and try really hard and still not be able to preserve these things 100%. So they get unrolled and they see there’s basically like this chicken scratch on them. And if you think about again, how tiny these things are, just a few centimeters long,there’s at least nine lines of text written in those few centimeters, just how tiny that text is. And it looks like a chicken scratch, and it’s really hard to decipher. But one thing that jumps out at Barkay right away is the name of God, the Y-K-V-K name of God, as we would say in Judaism, the four letter appellation name of God that is considered.

Schwab: The Tetragrammaton, I believe, is the very fancy English word.

Yael: Yes. Good. It’s not just hexagram that you’re teaching me. It’s Tetragrammaton. Yes, the Tetragrammaton. Yes.

Schwab: Ha ha. Because this is written in, I assume, a very old version of Hebrew, but one that we can read.

Yael: In ancient Semitic language, we believe it to be an ancient Hebrew, though even at that time there was more than one type of ancient Hebrew. There was a northern ancient Hebrew and a southern ancient Hebrew. There was Aramaic, there was Akkadian, there was Phoenician, there was Ugaritic.

Schwab: I was gonna say Ugaritic. I remember from taking intro Bible, that’s the.

Yael: You want to know who else remembers Ugaritic?

Schwab: Dr. John Monson.

Yael: Dr. John Monson. He mentions something about how the Ugarites, the people who speak Ugaritic, they actually wrote things in cuneiform on clay. And that’s why even though their city was destroyed, we still have artifacts of what they wrote because everything that was written on papyrus was destroyed, but everything that was written on clay survived, which again goes back to the ancient, the magic bowls we talked about where we don’t know how significant the bowls were. We see that there were a lot of them, but that’s what survived. There could have been 10 times as much written on papyrus and we would never know.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. But like, this is not incidentally survived because this, this was buried as a valuable object, right? Like we, this isn’t, this wasn’t found in a house. We know this was kept on purpose. We know that it was significant.

Yael: Yes, we certainly believe that it was in a burial chamber and intentionally in a burial chamber and not necessarily something that had been in a home that ultimately ended up there. Though again, that’s an argument among the archaeologists, particularly the ones who believe that this is from the Hellenistic period several hundred years later.

Schwab: Barkay sees the name of God and then decipher the rest?

Yael: He sees the name of God and he gets excited. He’s like, okay, there could be scripture here.

Yael: We’ll be right back.

BREAK

It takes a very long time to decipher everything else that’s in there. There was a woman named Ada Yardeni who was working on this project who noticed that there were three Tetragrammatons in each of the scrolls.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And in the way that they were placed on different lines and she consulted with a devout Jew, the person was described in the sources a devout Jew,who said that the only place in Jewish scripture that the Tetragrammaton appears in three consecutive lines like that is the priestly blessing. And then using several other techniques, including something I believe that they refer to as template writing or template reading, where they took the shapes of various letters that they were able to read on different lines and then overlaid them on other lines to see where they fit or how various etchings could have been part of those original letters. And they were able, and also this was obviously joined by very high-level photography and the use of microscopes. And they were able to ultimately reconstruct the priestly blessing among some other texts on both of these amulets, which is really amazing.

Schwab: Wow. And the two amulets are similar but unrelated to each other?

Yael: They both contain the priestly blessing, but their other text is not identical. What we believe is they were found in the same archaeological site and were both believed to have been in that one burial room, but they weren’t found right adjacent to each other. And also, I think because of the way that the ceiling collapsed courtesy of young Nathan, a lot of things were displaced and they had to go through a lot of dust and dirt to get to each of these various artifacts.

So really exciting, really hugely exciting stuff for the Jewish world, for the world of archeology, for the world of ancient languages. not to bring Indiana Jones back into it, but in one of the lectures I listened to, this was described as an Indiana Jones movie, also because one of the places that they referenced, not the place where this was discovered,they were in a place called the Cave of Horrors, which was not Gehenom, not Hell, but the Cave of Horrors. And they said this was better than the Holy Grail.

Schwab: That’s a great name. Yeah.

Yael: So it’s super just world shattering, literally, stuff for academia.

Schwab: Yeah. Yeah. I guess one of my questions, why is this not more famous? I have not heard of this before today. Why is this something that doesn’t, I don’t know, carry the same weight, isn’t talked about, especially if it’s significantly older than the Dead Sea Scrolls? Why are we not all familiar with the?

Yael: I think that it is very famous. I’m not disparaging you by saying that because I didn’t know what they were either. These amulets are in the Israel Museum. It’s very possible that both of us have seen them in person before and just never realized exactly. They are very famous.

Schwab: I’m just uninformed. Mm-hmm.

Yael: Maybe if we were before this point, people more interested in biblical archaeology or the excavation of Jerusalem, we would know more about them.

Schwab: And now they’ll be famous for the lay listeners, for the Jewish history nerds.

One thing that I do want to note, just because this is supposed to be about the material object itself and less about Nathan and his mischief and Barkay and especially Dr. John Monson, I do want to talk a little bit about the technology that was used to decipher these scrolls. You know, this discovery was made in 1979, which is very recent and that’s one of the things I find really fascinating about this topic.

We are talking about the oldest known epigraphic evidence of the Old Testament and we’re also talking about something that was just discovered in 1979 and I know some listeners might not believe this but that is very recently. I checked 1979 was the year that Rocky 2 came out.

So this is more recent than Rocky. Like Rocky is old compared to the discovery of these amulets.And for those of you who don’t know what Rocky is, he’s the old guy from Creed. So this is something simultaneously so new and so old, which I find really, really cool. So there was great technology already in 1979. There was obviously very good photography, but it doesn’t compare to what we have now or what’s developed over the ages it took about a decade from the initial discovery to the time that everything was unrolled and then deciphered for the first academic paper about this to be released into the world. And over that time, they had used a variety of photographic techniques and they were able to see the letters very, very clearly, especially under microscopes. But the photography once printed was really not that helpful because they just couldn’t get a great shot, whether it was because of the lighting or the material and the glare.

So what would happen is everyone would go up to the microscope and be able to see it. And then they would never agree on what it actually was because everybody’s, everybody’s perception of what they were seeing. It’s like, I’m going to, I’m going to draw what I see. And everybody’s description or drawing was different because they couldn’t get a really good reproduction.

So it took some time. After the initial publication by Barkay, more interest developed in this discovery. And he eventually teamed up with a group from the University of Southern California, where they have something called the Western Semitic Project. And I guess they have a lot of funding and a lot of resources, and they brought a team to inspect the artifacts. And they had one guy who they called their secret weapon who introduced them to a technique called light painting, which is where you focus light on one particular aspect of the artifact. And you then take a picture with long lens exposure, which is something that they do to photograph comets and other things in space that move very quickly. And through his technological prowess, they were able to get much better photography that led to much more consensus on what people actually could see. One of the things that they had to do was eventually tilt the scrolls, and that eliminated glare, I believe. So they got this fancy camera and they tilted the camera. And when the artifacts in the camera were tilted the same way, they were able to get consensus that these are actually images of what this is.

Schwab: What I’m hearing is like, thank God this was found in, you know, nineteen seventy nine, because if it was found a hundred years earlier, someone would have just opened it up and would have decomposed and we would have had no idea ever what was in there. But like.

Yael: Exactly. Or, you know, they might have tried their best and then it would have gone into a museum and then kind of the hub, the hubbub and the hype would have died down and who knows? Yeah, would they have gotten the money exactly? And that leads into the question that I kind of want to wrap up with, which is this is obviously a very expensive, very intense, very arduous process. And especially

Schwab: Right, like, yeah, like 10,000 other artifacts would be like, silver amulets found in Jerusalem, some sort of scroll inside, yeah.

Yael: Maybe in an age when the funding for higher education in the world might be dropping hypothetically. What is the value of this? What is the value of funding endeavors like this? what’s the value to you as a lay person, as someone who works in academia, as a Jew? What is the value that you see here?

Schwab: I’m definitely very much in this mindset from from doing this podcast and from some of the things that we’ve been doing this season, looking at some of these like really old, like thinking back to, you know, to our episode on the Merneptah Stele and like there’s something I don’t know, very, very much part of Jewish culture, which is like the I don’t know that that there is so much history that we are in ancient people.

And I, I don’t know, I really like this story because the Merneptah Stele sort of me in the mindset, like all we’re gleaning from that is like, okay, there was an Israel and there still is an Israel and like, we identify as the same people, right? Like, but what does that mean other than we’re still here using the same name? But this is very different, because like, this is a verse in the Bible that is like I was saying at the beginning, like, of my weekly practice and the idea that felt like we have proof that this is two and a half millennia of Jews placing importance on these verses that I don’t know hard for me to say I would put a price on that but that’s pretty valuable. I think that’s pretty important in contextualizing my present identity and practice.

CREDITS

Yael: Jewish History Nerds is a production of Unpacked, an open-door media brand. Subscribe wherever you’re listening to this podcast and follow Unpacked on all the regular social media channels. Just search for @Unpacked Media.

Schwab: And if you’re enjoying nerding out with us, please share this and other episodes with your friends and family. And most of all, be in touch with us by writing to us at nerds@unpacked.media. That’s nerds at unpacked.media.

Yael: Jewish History Nerds is produced by Jenny Falcon and Rivki Stern. Dr. Henry Abramson is our education lead. It’s edited by Rob Pera. I’m Yael Steiner.

Schwab: And I’m Jonathan Schwab. Thanks for listening.