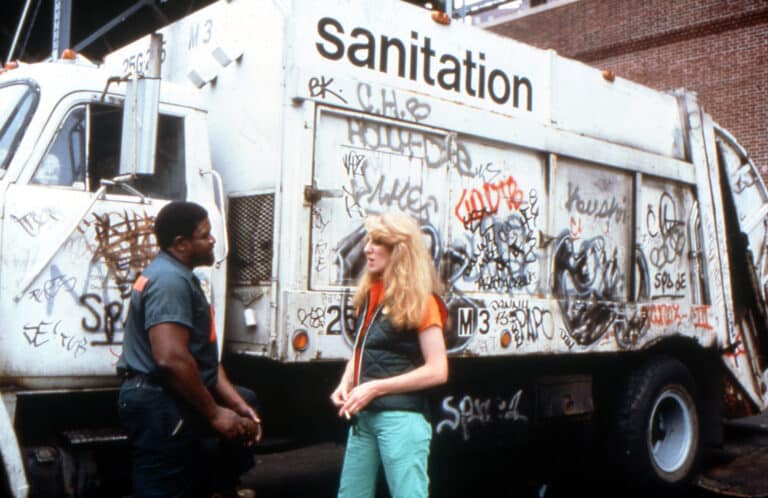

Art has long stood as a platform to help us see the world in a new light. However, for Jewish artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, it became something more: a tool for revolution, making the invisible visible. Through her work, Ukeles has spent decades spotlighting the overlooked and often invisible labor that keeps cities running, particularly the sanitation workers who clean our streets and perform other essential, unrecognized labor.

Despite her profound impact, Ukeles isn’t a household name and much of her work has been done without financial compensation. Her career spans continents and generations, from her performance work “Touch Sanitation” (1979-80), in which she personally shook hands with more than 8,500 New York City sanitation workers, to 2020’s “For → Forever,” a tribute to frontline workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now, Ukeles is finally getting her due in “Maintenance Artist,” Toby Perl Freilich’s new documentary that premiered at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival.

The film offers a moving portrait of art as both literal labor and an artist’s lifelong “labor of love.” It’s a powerful reminder that art can change the world and be deeply representative of the people it serves.

Freilich, the director of films including “Moynihan” and “Inventing Our Life: The Kibbutz Experiment,” spoke to Unpacked about the eight-year process of making “Maintenance Artist,” the emotional balancing act required to tell Ukeles’ story, and the documentary’s connection to Jewish identity and values.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

How did you first meet Mierle? What was it like building a relationship with her, both personally and professionally?

I had heard about the career retrospective of her work at the Queens Museum in 2016-17 and went to see it on the very last day. Mierle was there, and I introduced myself.

Eventually, a mutual friend connected us via email, and we got together for coffee — an encounter that lasted for three hours. I think we were both happily surprised at how easy the discourse felt, and yes, the Jewish connection was part of it.

I told her that I wanted to make a film about her, and she said, “No.” So I asked if I could film her going through her files at the Department of Sanitation in preparation for the acquisition of part of her archive by the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian and she said, “Yes.” That was eight years ago, and the film took off from there.

Your past work deeply explores Jewish themes. At first glance, “Maintenance Artist” might seem like a departure. What specifically drew you to this project?

I was impressed with the imaginative leap of “maintenance art,” by the scale of Mierle’s work, and by her creative range. I was deeply moved that she embraced and celebrated such an essential but underappreciated sector of the workforce.

I was also excited about the richness and scope of the story — it encompassed not just art, but labor, feminism, urban history, and environmental conservation, all set during the social and cultural upheavals of the late 20th century.

In all those respects, it was a story with depth and breadth, and I thought it would make a great film. And, of course, the fact that she was a ”crossover” artist – someone whose work flowed from a deeply Jewish core yet whose message was so universal – really excited me.

What was the directing process like? How did you approach gathering archival footage, interviewing Mierle’s family, and connecting with art historians?

The direction of this film, as is true of many documentary films, was driven by the crude reality of money. I started with one $5000 donation and then raised a couple more $5000 donations. That allowed me to at least start filming some events that were on Mierle’s calendar, like the one at the Whitney Museum where she spoke after they acquired her 1976 piece, “I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day.” It also helped me film some verité footage with her, like sorting through her archives to decide what to send to the Smithsonian.

Mierle was very generous in including me in meetings with the Smithsonian in which we reviewed what she had in her archive in the way of video and audio.

We determined that it was important for me to digitize some of that video material, which eventually served as the core of the archive that we worked with in the editing room. As I was able to raise more money, and as the arc of the film came into greater focus, we gradually digitized more material.

I always planned to interview people who could place her work in a larger art historical frame. Tom Finkelpearl and Larissa Harris had worked with Mierle over many years; Patti Phillips wrote the authoritative and comprehensive book that accompanied the Queens Museum exhibit; Nat Trotman, the Guggenheim’s curator of Performance and Media, had worked with Mierle when the Museum acquired some of her work; and Julia Bryan-Wilson had written a book that I loved called “Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era.”

The decision to interview family members came later, after we had a private screening of the rough cut and a number of people mentioned that the kids were a missing component for them.

What was the most challenging part of telling Mierle’s story?

The biggest challenge for me was finding the dramatic focus for this very, very large, unwieldy story that encompassed feminism, the history of the New York City Sanitation Department, Mierle’s Jewish roots, her pioneering work in “social practice art” and ecofeminism, the development of performance and conceptual art. Writing a logline was hell; I still haven’t written one that I think does justice to the film.

“Maintenance Artist” has a strong environmental and social consciousness — how intentional was that framing, and how do you see it resonating in today’s social climate?

The environmental framing was very much part of Mierle’s focus from the time that she wrote her Manifesto for Maintenance Art in 1969, so it was always going to be part of the framing. As she says in the film, personal, societal, and environmental maintenance issues were intertwined and “you can’t fix one without fixing the other.” My takeaway from Mierle’s environmental work is how harmful and hubris-filled our hyper-consumerism is. What is the planet supposed to do with all this stuff that we use briefly and then throw away?

Mierle briefly touches on her Jewish background in the film, including scenes of her husband wearing a yarmulke in their home in Israel. There’s also a powerful moment when she says her Orthodox upbringing shaped her commitment to improving others’ lives. Would you consider “Maintenance Artist” a Jewish film at its core?

Though Mierle and I are roughly a generation apart, we both grew up in homes that were strictly Orthodox but in which a broad-minded spirit prevailed. By the time I started working on the film, I had been growing more and more saddened by the rightward drift of the Orthodox community, segments of which were even starting to align themselves with the far-right. As the daughter of two Holocaust survivors, I was horrified to see my religious community cozying up to emerging proto-fascist political movements.

So, I thought it was important to expand the Orthodox Jewish narrative (and certainly when it came to art by Jewish visual artists) from the particularism of material symbols of Jewish culture to the core universal values that it embodied. Ukeles, though she embraces Orthodox traditions, was always challenging Orthodoxy to be more inclusive, less patriarchal, more humanistic. In this respect, she and I were very much on the same wavelength.

At the same time, Mierle does not fit neatly into any box or category, and she is passionate about retaining that kind of artistic freedom and flexibility. It’s important to both of us that she is not pigeon-holed as a Jewish artist or tagged with any other kind of essentialist label.

Personally, while working on the film, I found that contemporary art and religious observance rarely mix, which added an element of surprise to the story that I loved.

Mierle’s work reminds us of other Jewish thinkers and artists — from Marc Chagall to Karl Marx, or feminist pioneers like Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem. Where do you see her fitting in that broader legacy of Jewish artistic or feminist thought?

For me, the key thing was that she accomplished all that she did within the framework of being an Orthodox Jew. The greatness achieved by many of the others that you mention was almost always accompanied by a break with a traditional religious past, if that was where they came from. But Mierle did not see a contradiction between being strictly Orthodox and calling upon Orthodoxy to become more sensitive to feminism and other liberal values. And I loved her deeply humanistic interpretation of the Orthodox tradition.

Do you see a growing interest in Jewish identity or history in contemporary art or film? Where do you think this film fits in that movement?

I always knew that, though my motivation for making this film was rooted in something deeply Jewish, that factor would play a very small role in the film itself. Mierle is very wary of being tagged as a Jewish artist, or anything else, for that matter. She wants 100 percent freedom to make any art that she decides to make, without any categories. This film was never about identity in the narrow sense – it was always about values, and universal values.

Was there anything you wanted to include in the film but couldn’t due to time, tone, or other limitations?

I had tracked down a sanitation worker who had participated in Mierle’s “Touch Sanitation Performance” back in 1979-80 and who is in the archival footage we used in the film. I wanted to interview him; however, this was in the final stretch of finishing the film, and suddenly he had a health episode that precluded him from participating. I wish we had gotten to him sooner.

After immersing yourself in Mierle’s work, do you believe art has the power to change the world?

I’ve always believed that change tends to happen slowly and incrementally, one heart and mind at a time. Art has the power to unleash in people the potential for seeing something in a different way or solving a problem with a fresh focus. That’s enough for me.