When thinking about Jewish political leaders in the U.S., names like Justice Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish Supreme Court Justice, and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a trailblazer for women’s rights, often come to mind. Doug Emhoff, the nation’s first Jewish Second Gentleman, has also made history. Yet one pivotal Jewish-American leader is sometimes overlooked — Sen. Joe Lieberman, the first Jewish candidate on a major U.S. presidential ticket.

Once a steadfast Democrat, though often seen as right-leaning, Lieberman eventually carved his own independent path, voting with whichever party’s proposal was more in line with his convictions. He dedicated himself to bridging the growing partisan divide in Washington, but in doing so, he sometimes found the very relationships that had once defined his career slipping away.

The basics

Joseph Isadore Lieberman was born on Feb. 24, 1942, in Stamford, Conn. to Jewish liquor store owner Henry Lieberman and his wife, Marcia. His father’s parents emigrated from Poland, while his mother’s family came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Even as a young man, Lieberman was passionate about civil rights. He attended Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.‘s March on Washington, which inspired him to travel to Jackson, Mississippi, at 21 to support the Civil Rights Movement. As a Yale undergraduate, he covered voter registration efforts and the Freedom Vote for the Yale Daily News, drawing attention to a cause many mainstream outlets ignored. After earning his law degree from Yale in 1967, he practiced law in New Haven.

While in law school, Lieberman met his first wife, Betty Haas, while both were interning at the office of Connecticut Senator Abraham Ribicoff. The couple married in 1965 and had two children, Matt and Rebecca, before divorcing in 1981. Lieberman, an Orthodox Jew, later said their differing levels of religious observance were a key reason for their split, as Haas was a proud Reform Jew.

Though raised in a religious home, Lieberman deepened his commitment to Orthodox Judaism after the passing of his devout grandmother in 1967. He later found religious common ground with his second wife, Hadassah Freilich Tucker, a Modern Orthodox Jew and the daughter of Holocaust survivors. Together, they had a daughter, Hana, and Lieberman also became stepfather to Hadassah’s son, Rabbi Ethan Tucker.

Lieberman entered politics in 1970 when he was elected to the Connecticut Senate. He served for a decade, including three terms as majority leader. After an unsuccessful bid for Congress, he was elected Connecticut’s Attorney General in 1983, where he emphasized consumer protection and environmental enforcement. He argued Estate of Thornton v. Caldor, Inc. before the U.S. Supreme Court, fighting to ensure businesses could not force employees to work on their Sabbath. In his 1986 reelection, he earned more votes than any other Democrat statewide.

Joe Lieberman’s national political career.

In 1988, Lieberman pulled off a stunning political upset, narrowly defeating Republican incumbent Lowell Weicker to win a seat in the U.S. Senate. His victory, aided by a coalition of Democrats, independents, and even conservative Republicans, made him the first Orthodox Jew to serve in the Senate.

Throughout his career, Lieberman built a reputation as a political bridge-builder, a stance that earned both admiration and frustration. He worked across party lines on issues such as welfare reform and environmental protection. He also championed regulations on violent video games, playing a key role in the establishment of the video game rating system in the 1990s.

In 1992, when Arab Americans felt like Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign was ignoring them, they reached out to Lieberman to get the Arkansas senator’s attention. Despite their vast different stances on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Lieberman thought their exclusion was unfair. After a single phone call from Lieberman, Clinton’s campaign opened its doors to Arab American outreach.

Lieberman was not afraid to break with his party. As chair of the Democratic Leadership Council from 1995 to 2001, he frequently challenged Democratic orthodoxy. In 1998, he became the first high-profile Democrat to publicly criticize President Bill Clinton over his affair with Monica Lewinsky, though he ultimately voted against Clinton’s removal from office.

“It was a very hard thing for me to do because I liked him, but I really felt what he did was awful and that unless I felt myself if I didn’t say something, I’d be a hypocrite. I also felt that if somebody who was supportive of him didn’t say something, it would not be good,” Lieberman said in 2014 of his decision to speak out.

2000: Lieberman and Gore

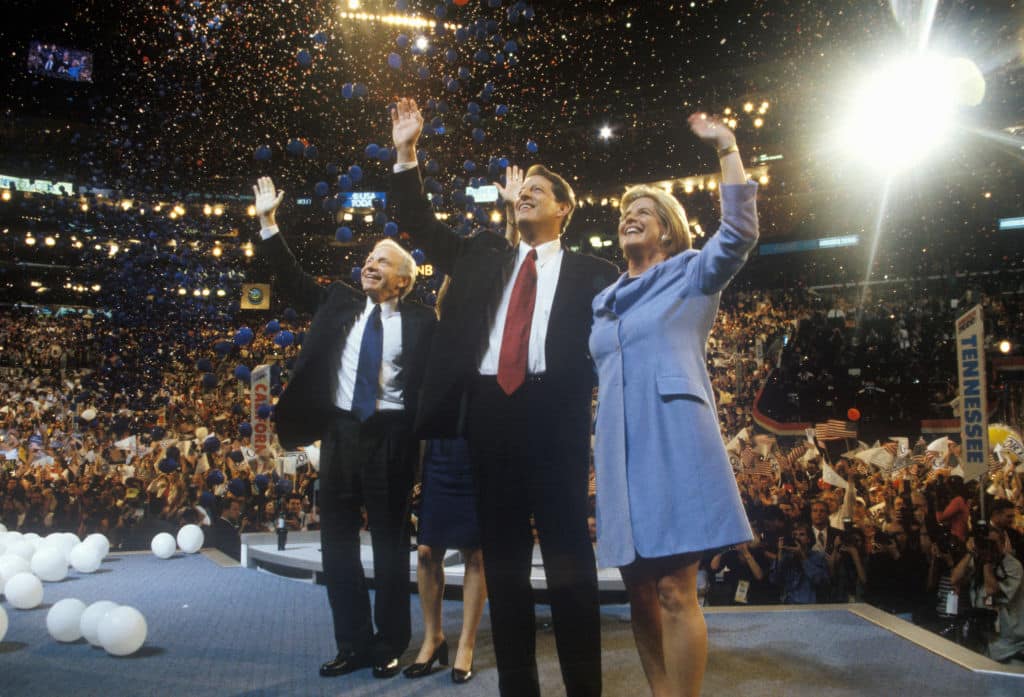

Despite being more conservative than Vice President Al Gore, Lieberman was chosen as his running mate in the 2000 presidential election—a groundbreaking moment for religious inclusivity. Not only was he the first Jewish person on a major-party presidential ticket, but as an Orthodox Jew, his candidacy raised unique questions about how he would navigate Shabbat while serving in high office.

One adviser joked that Lieberman would work “24/6,” and campaign staff worried that his observance of Shabbat might hurt his chances. However, Lieberman explained that Jewish law permitted him to fulfill government duties on the Sabbath, just as a doctor can treat a patient in an emergency.

A spokesperson for Lieberman explained that the senator “refers to himself as observant, as opposed to Orthodox, because he doesn’t follow the strict Orthodox code and doesn’t want to offend the Orthodox, and his wife feels the same way.”

“It was an electric moment,” Ira Forman, the former director of the National Jewish Democratic Council, said of Gore’s selection of Lieberman as his vice president. “It galvanized the feeling that everything is open to you.”

The Gore-Lieberman ticket won the popular vote in the 2000 election by a margin of more than 500,000 votes, but after a weeks-long legal battle was named not the victors of the election. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Bush-Cheney ticket, denying Gore and Lieberman a recount of Florida’s votes, which would have granted them the election in a still-controversial decision.

Lieberman’s return to the Senate

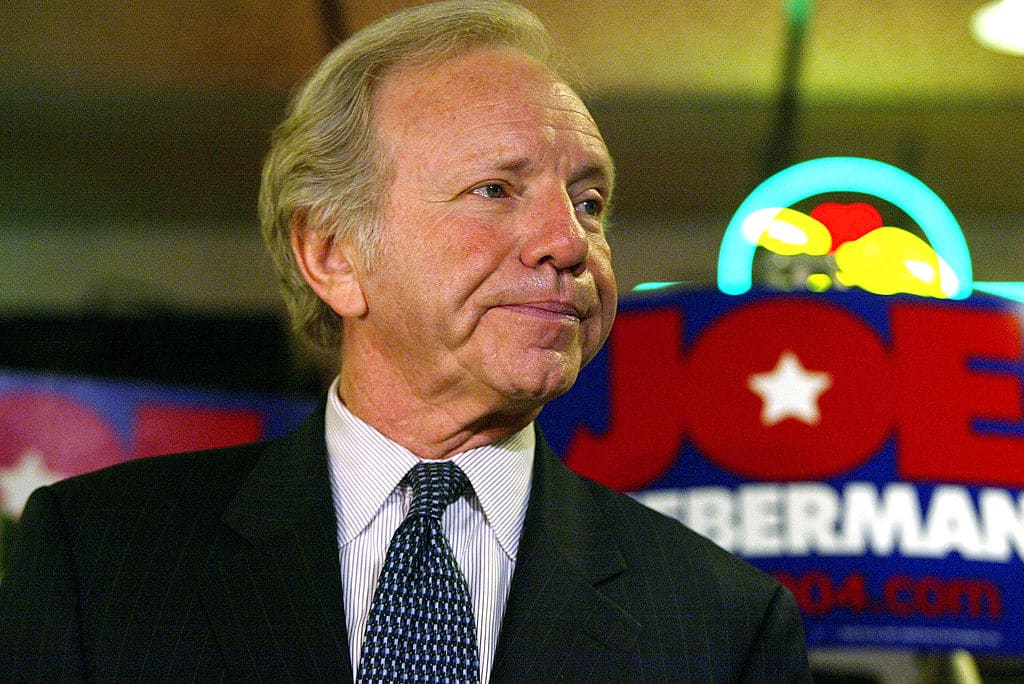

Lieberman set his eyes toward the 2004 Democratic presidential nomination, as many Americans were becoming disillusioned by the war in Iraq, the Connecticut senator made his support for the war a staple of his campaign. His hawkish stances alienated many Democratic voters. The final blow came when Gore endorsed another candidate.

In 2006, his support for the war cost him the Democratic Senate nomination to anti-war candidate Ned Lamont. Undeterred, Lieberman ran as a third-party candidate and won, proving his bipartisan appeal with 50% of the vote.

Lieberman further defied party lines in 2008 by endorsing Republican Sen. John McCain for president over Barack Obama, despite the latter having previously supported him in his Senate run. McCain even considered Lieberman as a running mate, a move that further distanced him from many Democrats. However, Lieberman and Obama later worked together productively.

“He said to me, ‘Look, I thank you, but I understand that one of the reasons I have the opportunity I have now is because of what you’ve done in the past.’ I didn’t know whether he meant that I had been in the Civil Rights Movement or that I had run as the first Jewish American running for national office. So in that sense, I broke a barrier, and maybe he felt that opened the doors wider for him,” Lieberman recalled of an interaction with the first Black president.

Lieberman was also a leading advocate for LGBTQ+ rights, sponsoring the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal Act of 2010. He famously remained in the Senate to vote on the bill despite it being Shabbat, and when a Republican donor threatened to pull financial support over his advocacy, Lieberman stood firm.

In his final years in the Senate, he helped create the Department of Homeland Security, played a key role in the response to the H1N1 influenza outbreak, supported women’s reproductive rights, and was the crucial 60th vote needed to pass the Affordable Care Act.

Lieberman’s Jewish legacy

When Lieberman revealed he would not seek reelection in 2012, he reflected with deep emotion on his journey — how the grandson of Jewish immigrants had risen to a place where he was once within reach of the vice presidency.

“I can’t help but also think about my four grandparents and the journey they traveled more than a century ago,” he said. “Even they could not have dreamed that their grandson would end up a United States senator and, incidentally, a barrier-breaking candidate for vice president.”

He became widely known for his deep commitment to Jewish observance in public life. Throughout his career, he would walk four miles from his Georgetown home to the Capitol on Shabbat to cast crucial votes, including one to block a Republican filibuster. He chronicled these experiences in his 2011 book, “The Gift of Rest: Rediscovering the Beauty of the Sabbath.”

“While he wore his Jewish practice with deep humility, he did so proudly and publicly, and he always believed that his faith connected him to others more than it separated him out,” his stepson Rabbi Ethan Tucker wrote in an obituary for the senator.

He is remembered as a supporter of the relationship between the U.S. and Israel, and for being one of the most high-profile Jews in the nation. He even co-sponsored the Jerusalem Embassy Act of 1995, which urged Clinton to move the U.S. embassy in Israel to Jerusalem.

In 2021, he praised the Biden White House’s ongoing support for the Jewish State, praising “the quiet and effective diplomacy of President Biden, who was not drawn in by the left of the Democratic Party to essentially take a stand against Israel.” That same year, he joined the Muslin-Jewish Advisory Council, which was formed to address the spike in anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish hate in the U.S.

Following his career in public service, Lieberman began educating the next generation of Jewish leaders, serving as the Lieberman Chair of Public Policy and Public Service at Yeshiva University, and teaching an undergraduate class in political science.

Until his death, Lieberman continued to be an advocate for bipartisan unity, helping found No Labels, a non-profit that urges Democrats and Republicans to work together to find legislative solutions.

Joe Lieberman passed away on March 27, 2024, at age 82, from injuries sustained in a fall. His legacy endures as a trailblazer for Jewish Americans in politics and a steadfast advocate for bipartisan leadership.