Yael: From Unpacked, this is Jewish History Nerds, the podcast where we nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history. I’m Yael Steiner.

Schwab: And I’m Jonathan Schwab. And today we’re gonna talk about a specific object. It’s not part of a series, it’s not abstract, it’s one clear specific object. And one of the most important things about this one is that it is very, very, very old.

This is older than anything else we’ve ever talked about. I went back and looked not just at this season, but all seasons.

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: And it’s and it’s by a huge margin as well.

Yael: Is it the original tablets of the Ten Commandments? Is it Eve’s Apple?

Schwab: Ooh, all right, well, it’s not as old as Eve’s apple. But funny you should mention tablets because you’re around, you know, the right time and place, this is an artifact from ancient Egypt–

Yael: That’s cool.

Schab: That we date pretty definitively to like a very narrow span of years. So this is like somewhere between, I think it’s 1209 and 1213 BCE, 1200 years older than the next oldest thing we’ve ever talked about.

Yael: Wow, that’s cool.

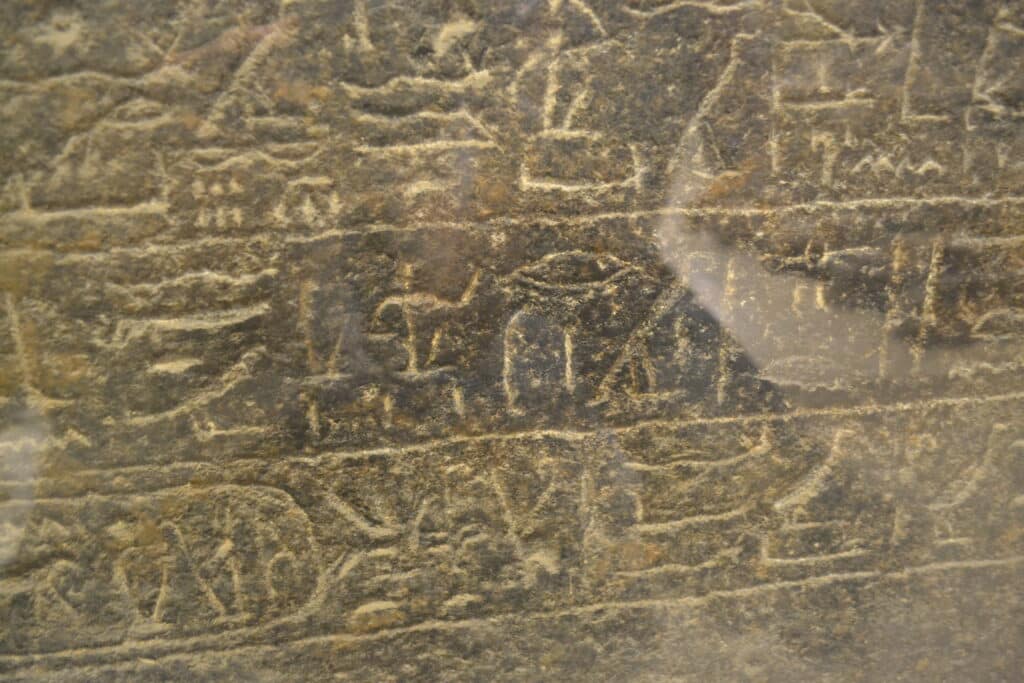

Schwab: Yeah. And in remarkably good condition for something this old, it is the Merneptah Stele.

Yael: Don’t know it. I was about to say, I know Steely Dan,

Schwab: So this is a different this is S-T-E-L-E, which is a word, I think that generally connotes just just some sort of obelisk or monument obelisk.

Yael: Obelisk? I know what that is. That’s like a tall pointy thing. There’s one in Central Park. From Egypt. Probably not.

Schwab: Yeah It’s an ancient Egyptian thing. It’s a huge slab of granite stone onto which is carved hieroglyphics. And Merneptah is the pharaoh from that time. The Egyptians kept really good historical records.

Yael: Jewish enemies tend to do that.

Schwab: So yes, exactly what we’re going to get into. So we know who Merneptah is, we know when he ruled, we know all of these things, and we have this stele, which was discovered in late 1800s, I think it was 1896, by a Egyptologist, who was excavating some site, some temple, and saw this huge slab. Brought in his friend to help him translate it, and they start going line by line translating this thing.

There are lots and lots of ancient Egyptian steles talking about what pharaohs did. And like many of them, this one talked about Merneptah and all the things he built, most importantly his military conquest. He had a very important military campaign against the Libyans and then also a military campaign into the land of Canaan. And this was, I guess this is the equivalent of a head of state giving a press release or in 2025 going on a Twitter or X or social media platform of choice, know, having somebody chisel out a long statement of just all your military victories onto a huge slab of granite that you then put somewhere so people can read.

Yael: When I think of an obelisk, like they’re usually outdoors, like taller than a building like the Washington Monument. Or there’s one, think like in the Place de la Concorde in Paris, like they’re very big to my knowledge. So is this that?

Schwab: Yes. This is big. It’s not that big. This is more, like a big billboard, basically just a huge rectangular shaped rock. It’s about 10 feet tall and three feet wide.

Yael: Okay, cool. And where is this right now?

Schwab: Right now it’s in a museum in Cairo. And again, like I said, in pretty good condition. If life takes you to Cairo, you can see it. And if you can read hieroglyphics, you can read it. But larger than a person, you know, and I think like fairly impressive there in that size. When you think about writing, this isn’t a tablet. It’s not something you can hold in your hand. It’s big, but not a gigantic monument.

And I’m sure you’re wondering, what is possibly written on this thing? Why are we talking so much?

Yael: Well, I’m sure what’s written on it is really interesting. I’m just really curious how we know what it says because you’re saying it’s in hieroglyphics.

Schwab: We can, when I say we, I don’t mean like me specifically, but we can read hieroglyphics because I think we have so many of them and people have studied it for so long that we actually have very high degree in confidence in what we’re usually reading because we know what these symbols mean we have multiple examples or instances of them appearing in different places and we’re able to decipher and make sense of it all so we can we can read hieroglyphics. I printed out the like a translation of this but also an original of like what the hieroglyphics looks like me, printing it out, feeling confident, like, yeah, I’m gonna, you in the course of the two weeks I’m spending preparing for this, I’m gonna teach myself how to read hieroglyphics. It’s a little more complicated than any language I’m familiar with, so I did not get that far in that project.

Yael: Sure. Okay.

Schwab: But among the many things it talks about when talking about Merneptah, getting to, at the very end of it, after a great amount of detail on Merneptah’s victory over the Libyans in that military conquest. It talks about the military conquest in Canaan. And I’ll read, this is one version of a translation, but I’ll read the last couple of lines out.

Yael:

Mm-hmm.

Schwab: “The princes are prostrate saying peace. Not one raises his head among the 9 bows. Desolation is for Tehanu. Hati is pacified. Plundered is the Canaan with every evil. Carried off is Ascaluni, seized upon is Gezer. Yanoam is made nonexistent. Israel is laid waste, its seed is no more.” And then it continues, went to say, “Taharu has become a widow because of Egypt. All lands together are pacified. Everyone who was restless has been bound.” So, yeah.

Yael That’s very intense. It’s… prosaic.

Schwab: Yeah, Merneptah was very successful. And this is also how things were written, of like, obviously completely destroyed all of these enemies. And we’ll probably come back to this, but it’s pretty hyperbolic. you know, they’re like, pretty shortly after this, we’ll see another thing saying again that they, you know, someone fought against Ascaluni and completely destroyed them again.

But the real significance of this. And when this was first discovered in 1896, the Egyptologist who was translating it was looking at the line that I read, Israel is laid waste because the hieroglyphics there, they were trying to figure out, know, okay, we’re familiar with the Ascaluni, we’re familiar with Gezer, which city, which people are we talking about here? And almost immediately, the thought and theory was, okay, we’re pretty sure this says Israel, and that was a huge deal at the time and remains a huge deal today because this is by far the oldest mention of Israel that we have in the historical record. This is a very, very old artifact saying there is a people that we’re calling Israel, that dates, and this artifact is from the year 1200 BCE, other than the Bible, which, you we don’t have a physical Bible that’s 3,000 years old. We know what times the Bible says it’s referring to. We know that we have copies of copies of things, but like, we don’t have a Bible that’s 3,000 years old. So this is an object, 3,200 years old, that is clearly talking about a people named Israel.

The next oldest thing, there are a couple other artifacts from like this, general time period of the Iron Age, which is within a couple of centuries of this, but like the next oldest things that we have that mention Israel that we can confidently date are all like three to 400 years later than this. So this is like really, really, really old talking about Israel.

Yael: Do we have any other archaeological relics that we believe are contemporaneous to this that tell us what else is going on at this time? Maybe that’s outside the scope.

Schwab: yeah, There’s plenty of other Merneptah stuff like we know a surprising amount about Merneptah, even though he was only Pharaoh for 10 years. Stinks. It’s a real once is it Prince Charles or King Charles now? Right is the is. So so, yeah, Mernept Mernept Merneptas father, Ramsey’s the second.

Yael: Like his mother lived to a ripe old age and then he only got to be king for a minute.

Schwab: was Pharaoh for something like 60 odd years or something. And Mernepte finally became Pharaoh starting at the age of 70 something and ruled for like 10 years.

Yael: so really apropos analogy.

Schwab: Yeah, really similar.

Well, obviously, King Charles, he should live and be well, and hopefully his reign will, yeah.

Yael: Until one hundred and twenty.

Schwab: But yeah, like, Merneptah was an old man by the time he finally became Pharaoh and was not, I don’t know, his conquest of the Libyans, I guess, is of some importance, but he’s not a hugely important Pharaoh, and yet we know a fair amount about him. And have his mummy, by the way. We got it, we identified it, we found it. It’s also in a museum in Egypt. And again, just like, I can’t emphasize this enough how long ago this was. Like it’s just like a mind-bogglingly long time.

Yael: Right, if you think about how long ago Jesus was, it’s 1200 years before that. So, what is the significance of this particular stele or this particular relic to us both as humans in 2025 and as Jews?

Schwab: Yeah, well, think the significance as humans, think, is the significance as Jews.

Yael: Not that those two things are mutually exclusive.

Schwab: Like, this is significant because of this mention of Israel. Nobody is focusing on like, okay, wow, he carried off Yanoam. Like, Yanoam, I don’t know that much about Yanoam, but maybe Yanoam was getting carried off all the time.

Yael: You know him? I barely know him.

Schwab: But so this was for a while called, I think, the Israel Stele. And then for understandable reasons, the Egyptian authorities have pushed to say maybe we should call it the Renepta Stele.

Yael: So it’s significant because, yeah, because like this very, very old mention of Israel is a big deal. For all the haters, who don’t really believe that Israel has a long history or that Jews exist or that the story of the Bible, that there was a people named Israel or in a place called Israel, like this is pretty irrefutable evidence that this is not a recent thing. This has been going on a very, very long time. Yeah.

Yael: fascinating.

Schwab: Yeah, it is. It is fascinating. There’s obviously, I think, like a renewed interest, you know, in in 2025 and a lot of discussion, you know, like and you’ll see, you know, on the Internet every once in a while, someone will be like, well, here’s a map of the Middle East from, you know, 1932. And it doesn’t say Israel on it, it says Palestine. You know? So like Israel never existed. Like, OK, well, here’s a description of the area from 1209 BCE and Israel is on it.

Yael: So I’m gonna have to cut you off for one second because it is the second day of spring, which means Pesach is coming, so this is great, this is perfectly timed.

Schwab: Mm hmm. Yes. This is yes. It

is a perfect timing. Yes. It’s a perfect timing thing. It’s a great topic to talk about for Passover, not just because it’s a story about ancient Egypt and the Jews, you know, ancient and Egypt and Israel fought wars and had what to do with each other for for many, many years. But

But there’s an exodus element here. And this is the part where I do want to say disclaimer, we’re departing slightly from strong historical evidence to speculation, this is, hmm, we don’t usually get into it because we don’t usually discuss things that are this old, but reconciling, you know, the archaeological excavations, written records of contemporary things, modern scientific approach to history, reconciling that with the written text of the Bible, especially the earlier parts of it, can get complicated and thorny, finding historical records that indicate the exodus in any way is very, hard. There’s not a lot of that, or really like any.

If we were trying to try to date that, try to figure that out, there’s some indication there’s an influx of population in the hill country of Judah at a certain time from excavations that we can tell. the main candidate for the Pharaoh of the Exodus is Ramses II.

Yael: Well, that’s what I was going to say. I didn’t want to interrupt you when you mentioned that he was Merneptah’s father to say that I thought Ramses II was the Pharaoh of the Exodus from a variety of sources, but from the Prince of Egypt. Obviously.

Schwab: Yeah, but most importantly, yes. Or the Ten Commandments, right? Right?

Yael: I just want to shout out my fam. We watch the Prince of Egypt every single year on the day before Pesach to re-familiarize ourselves with our animated history. And Ramses II played very capably by recent Academy Award loser, Ray Fiennes, who is an amazing Egyptian. Shout out the English Patient, everyone should see it.

Yael: The Prince of Egypt seems to indicate that Ramses II, the quote unquote brother of Moses, raised together in the same home after Moses is rescued by Pharaoh’s daughter, is the one who hardens his heart and he’s the Pharaoh.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

is the Ramsey’s, yeah.

So, yeah. So again, we’re in the realm, more of speculation, but we know that this name Ramses appears in the Bible in the context of the story of Exodus. We know that there’s a city named Ramses. know that Ramses is the name, that there is a Ramses II, that that is this pharaoh, he’s Myrnepta’s father. We also know that Myrnepta moves the capital of Egypt to a city called P. Ramesses or Pi Ramesses.

Yael: Interesting.

So there’s a big connection there just in the name. We also know that Ramesses II ruled for a long time and the Pharaoh of the Exodus story has to be a long time ruler of Egypt. can’t have been Merneptah, he ruled too short. It needs to be somebody who had a long rule and thus the story would make sense in that whole context. And we also, it’s important to note, these aren’t perfect records, so we don’t know what it is that we’re missing or not missing, and the things that survived, like this stele, do not generally record negatives, only positives. So, like, an exodus of slaves or plagues affecting Egypt are not the types of things that would get written down on something like this. Right.

Yael: Right, understood. It’s the victory bias.

Schwab: So, Israel is significant enough that Merneptah’s victory against them warranted being written down on this thing, which means, like it’s not just city, some group of people, but like important enough that it’s of relevance. So if you were writing down a list of like, here are the people I defeated, you want the list to sound impressive, so you’re not gonna mention someone who’s of no relevance. Which, again, slightly in the realm of speculation, perhaps this is significant because that is the people that his father, Ramses II, suffered a defeat at the hands of, or suffered setbacks at the hands of, right? Or were the bad guys in Ramses’ story in some way.

Yael: Right. Right.

interesting.

Schwab: Yeah. It also means, on the level of significant, it means that this can’t have been just some small tribe of people. Israel needs to have been significant enough to warrant being on this list.

Yael: So regardless, regardless of whether not Ramesses II was the guy, Israel was its own unique entity of people at this time and of a level of power that beating them was something of note. So…

Schwab: Yes, exactly.

Yael: So this is a really clear indicator that peoplehood among whatever people you want to call the Israelites existed at 1200 BC, whether or not you want to talk about them having been freed slaves or not, or having come from Egypt or not. In 1200 BCE, there was some conglomeration of people living in the holy land that went by the name Israel, of the Israelites. That’s a good talking point. I do like it.

Schwab: Yeah, exactly. Yes. Yeah. That’s a big deal. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Let’s take a quick break.

Yeah. This is two lines in this whole steely. in these two lines, whatever it is, the 15 total symbols that we’re talking about have been dissected to an incredible degree of people debating over tiny things. So there are three things on the level of like, deep-cut hieroglyphic language questions here. But there’s three things that I want to talk about specifically within these two lines. And some of them connect to what you just said. The first is, how do we know that it says Israel? Like, how do we know that these are the symbols connoting Israel? The second is the determinative. I’m sure you’re familiar that with determinatives in hieroglyphics,

Yael: Absolutely not.

Schwab: Yeah, and the question of the determinative being used here, because it’s an odd one.

Yael: Is that like a legend or like a dictionary that tells you what the symbols mean?

Schwab: Okay, so let’s, we’ll go through those two and we’ll come back to the third point. So the first one, Israel, like how do we know that it’s saying Israel? Because it’s, just to emphasize like how much you need to know to understand what you’re looking at, to me it looks like it’s, I don’t know, two fan shapes in a row and then a line with circles in it above two lines above an oval.

is the second one, and then a one fan shape and a bird, and then an eye maybe? Like that, and that, it is emojis, and some of the emojis mean whole words, and some of the emojis mean sounds. So these are sounds, this is like a is sound, se sound, ri sound, and then like r or l sound, so like it spells out Israel, but again, when it was first seen,

Yael: Okay.

Schwab: It’s emojis. It’s emojis.

Yael: Okay, that’s so interesting.

Schwab: the discoverer and his Egyptology, a German philologist by name of Wilhelm Spielberg, because of course. sorry, it’s Spiegelberg. It’s even more German than I thought. No, no, no.

Yael: Interesting. Wow.

Schwab: So they were looking at this and trying to sound out, they’re like, okay, what does this say? Isra-er? Isra-er? And pretty quickly they were like, okay, we’re pretty sure this says Israel. We’re pretty sure this is sounding out Israel. This has been confirmed, echoed, reaffirmed by a lot of scholars, including some who point to later iteration, like how Israel is talked about in much, much later.

Hieroglyphics like yeah, this is consistent with the way it would be written Even if not exactly there are some like really fringe opinions again I think the part of it is like there are haters who just who just don’t want to see this being the case So there’s like some who are like it doesn’t say it It’s it’s it’s jezreel, but it’s like a really strange spelling of jezreel, which is it which is a different thing That’s not israel. That’s that’s like referring to a different people or a different valley, you know or yeah or like some other thing and

Yael: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Schwab: Those are really largely dismissed because they rely on misspelling or a very strange pronunciation of it. The vast majority of scholars are like, this says Israel. It makes sense that it says Israel.

Yael: So I didn’t realize that there were symbols in hieroglyphics that corresponded to spoken sounds. I just assumed that every picture meant something.

Schwab: Yeah, the best comparison from what I understand is that it’s a little bit similar to, if you’re familiar with ASL, American Sign Language, is that there are signs for words, but there are also signs for letters or sounds. So you can spell out your name, but you could also have a sign for a name of something. So there could be one sign, or you could spell it out.

Yael: Mm-hmm. Got it.

Schwab: So if there isn’t a sign that everybody would recognize for Israel, then you can spell out Israel.

Yael: I think I’ve just been conditioned to think that these pictures are telling a story, not even that they’re a language, that they’re simply an illustration of what happened. And then also Billy Crystal in When Harry Met Sally posits, as one does, that hieroglyphics is just a comic strip about a character named Sphinxy.

Schwab: So I think that is like usually or somewhat I don’t know consistently the case but there is but there is also this This other way of expressing things. But to that idea like so Israel is spelled out in this way, but then to explain What it is that that you know when we spell out it spells out this word to explain what kind of word is this, there’s something called a determinative, which is a symbol following these, like spelling out things saying like, and this is what this type of thing is. And the determinative that is used here is that of a people, which is a throw stick and then a man and a woman above three lines, which like indicates it’s a male and female population, plural, and some sort of group of people.

And really interesting because the determinative that is used for the other places that are mentioned is that of a city state and Israel is not a city state.

Yael: Wow. So interesting.

Schwab: It’s a people and not a city state. And there’s a ton of really interesting scholarly discourse on this of like, what does that mean? Did they not have a fortified city? Were they a little more like nomadic? Were they, you know, like all sorts of different theories on like, what is the significance of the, if you ever meet, I don’t know, like an Egyptologist, you can be like, tell me what’s your take on the question of the determinative for Israel in the Merneptah Stele?

Yael: So this is unique. There are no other peoples–

Schwab: Right, all the other ones, the Gezer, Yanoam, Ascaluni, which is Ashkelon, by the way, those are all the determinative of a city-state. But this one is different.

Yael: Wow. People without a home.

Schwab: Which is very Jewish-y, right? It was just like, Israel, it’s not just about the place. It’s like we are a people, you know, but it’s also totally possible that it’s just an indication, like they didn’t have a fortified city. You know, because the other ones were fortified cities. Yeah, the other ones were fortified cities and maybe they, Israel did not have fortified cities. Maybe they did not yet have fortified cities because they were.

Yael: Interesting. And because there were other fortified cities at this time, allegedly.

Schwab: So newly having come from their slavery and so yeah, can take you in all sorts of really interesting directions. Yeah. Yeah.

Yael: Right. They were refugees. They hadn’t yet settled, which makes sense. Again, I’m totally using, I’m using biblical timeframes and applying them to this secular historical record. But if Ramesses II was the Pharaoh at the time of the Exodus and then the Jewish people were in the desert for 40 years and then only crossed the Jordan into Canaan at the end of that 40 years and Ramesses II was Pharaoh for a really long time, it works that contemporaneously, Merneptah may have been ruling, his short 10-year tenure as Pharaoh could have been around the time when those people, the Israelites under Moses or Joshua or whoever comes next because Joshua and then whoever comes next is contemporaneous to Merneptah. It totally, it works. If you want to make it work, it works.

Schwab: This would be, well, if it’s in, if it’s in Canaan, it’s under Joshua. This didn’t enter the land, but yeah.

Mm-hmm. Yeah. Yeah.

It works. Exactly. Yeah.

Like I think again, I think it lends itself to some imagination, some speculation, but takes you to interesting places.

The last language level thing that I want to talk about, just in this, again, it’s just literally one line or two lines depending on how you count it about Israel, is it says, Israel is laid waste or destroyed, however you want to translate that part. And then the second part of that is its seed is not. And that also, there are two schools of thought of what that means.

Yael: They don’t have land. They can’t plant. That’s one. That’s PG.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Right. yeah. Right. So one of them is, yeah, is like the literal, like we’re talking about their actual grain, you know, or maybe their store of grain was destroyed, which again, if they don’t have a city state, okay, they’ve like stored in some way or they planted something. And like, in addition to destroying the people, they also destroyed their ability to regrow.

Yael: Right, but obviously I’m more inclined towards the second meaning.

Schwab: And the second meaning is, like, their children, their progeny are destroyed. Which again, a lot of this is very hyperbolic but that would imply that what Merneptah is saying here is, there was a people called Israel and I have completely wiped them out. They are no more and there will no more be a people called Israel, but like, there is something so interesting and so very in line with so much of Jewish history that of course the oldest mention of Israel is a record of someone killing them.

We absolutely should not take at face value someone saying on one of these steles that they wiped out the entire people because this is like all over, not just with Israel, but like all over the place all the time. People say, and we completely destroyed these people. And then like 10 years later, we went to battle and completely destroyed these people again. I don’t think you did it right the first time, if that’s the case. And I’ll say also, that’s not just limited to Egyptian artifacts. Like you do occasionally see that like in the book of Joshua like there are times where there’s a city that’s completely destroyed and all of its people killed and then Like a decade or two later a battle against the same city.

Yael: I think you’re pointing out something really important about the historical record. We are using these images and language so precisely in order to figure out what actually happened and simultaneously acknowledging that there is artistic license in language and there’s hyperbole and there’s metaphor and how, you know, on the one hand, we need to trust academia and trust our intellectual instincts about what certain things mean. And at the same time, we have to acknowledge that different people convey ideas differently, not only via language, but via intent.

Schwab: Yeah. exactly. Like, in teaching my kids, I try to teach them to be critical thinkers about everything they see. And like, the way that I usually summarize that is, who benefits? Like, when you read something, okay, if that is the case, who benefits? So, as I usually do in practicing to talk about this, I talked about the Merneptah Stele with my eight and a half year old son, who at the very end of it told me this was not as interesting as some other stuff. All right, thanks, Nadav. So I add, who benefits? The military, his military conquest to seem as complete and as important as possible. So we should not, like you’re saying, take at face value that this means that Israel was completely destroyed, especially because we have, we certainly know this, like we have a lot to go on to indicate that Israel was not 3,300 years ago, 3,200 years ago, completely destroyed.

Yael: Right. And yet we still have to use the Merneptah Stele and other things that it conveys to us in order to advance the historical record. So we have to use it and take it at face value and also take it with a grain of salt. It’s a challenge, but I do like that lesson, the way you frame things for your kids.

Schwab: Thanks. The last connection I want to make, are you familiar with the poem Ozymandias?

Yael: I’m familiar with it in that I know it exists and maybe when you tell me something about it, it might ring a bell, but I can’t quote it to you right now.

Schwab: Sure. So it’s a poem by Percy Bisse Shelley.

Yael: Shelly’s, my mom’s name is Shelly too. Shout out Shelly.

Schwab: This is a poem. I remember encountering it at some point in high school and for whatever reason it stuck in my brain from then. I’ve always really liked it. I won’t read the whole thing, but it’s Ozymandias, which is by the way, the Greek name for Ramses. So it’s about, it’s going back to our favorite Pharaoh.

But the poem is about someone encountering a statue of Ozymandias in the Egyptian desert. And this giant statue is totally shattered and there’s like two vast and trunkless legs. So like just the bottoms of the legs are still there and a broken face lying nearby. And on the pedestal, these words appear.

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings. Look on my works, ye mighty and despair. Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.

It’s this amazing image, I think, of this broken statue in the Egyptian desert. And on it, it says, look how powerful I am and look at all the things that I’ve done. And clearly the original context was supposed to be that there were a lot of buildings all around it, but like all of that is gone now and all that’s left now is this very ironic thing saying like, look how powerful I am and it’s just a broken statue with that written on it. And I cannot help but think about the Merneptah Stele and the same sort of thing. Like Myrneptah, you worked so hard in all of your military conquests.

you in all the places you destroyed. And yet, your legacy now, the thing you are best known for, is mentioning a people who have outlived you by 3,000 years.

Yael: Thank you so much for introducing me to this concept that, sorry family, I will now be talking about a lot at our Seder. Gonna print out a bunch of articles and make everybody really nervous before we start.

Yael: Jewish History Nerds is a production of Unpacked, an OpenDor Media brand. Subscribe wherever you’re listening to this pod, and follow Unpacked on all the regular social media channels – just search for @UnpackedMedia.

Schwab: And if you’re enjoying nerding out with us, please share this and other episodes with your friends and family! And most of all, please be in touch by writing to us at nerds@unpacked.media. That’s nerds@unpacked.media

Yael: Jewish History Nerds is produced by Jenny Falcon and Rivky Stern. Dr. Henry Abramson is our education lead. It’s edited by Rob Pera.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab.

Yael: And I’m Yael Steiner.

Yael and Schwab: Thanks for listening

CREDITS

Yael: Jewish History Nerds is a production of Unpacked, an OpenDor Media brand. Subscribe wherever you’re listening to this pod, and follow Unpacked on all the regular social media channels – just search for @UnpackedMedia.

Schwab: And if you’re enjoying nerding out with us, please share this and other episodes with your friends and family! And most of all, please be in touch by writing to us at nerds@unpacked.media. That’s nerds@unpacked.media

Yael: Jewish History Nerds is produced by Jenny Falcon and Rivky Stern. Dr. Henry Abramson is our education lead. It’s edited by Rob Pera.

I’m Yael Steiner.

Schwab: And I’m Jonathan Schwab. Thanks for listening.