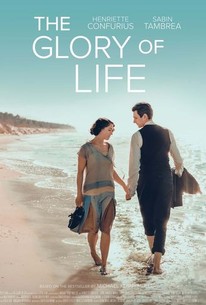

Walking into a screening of “The Glory of Life” at the New York Jewish Film Festival, I wasn’t sure what to expect. To be honest, I forgot what the movie was about, which made it difficult to engage with at first. As the story unfolded, I gradually realized “The Glory of Life” told the story of Jewish writer Franz Kafka (Sabin Tambrea) and his relationship with Jewish actress Dora Diamant (Henriette Confurius) during the final year of his life. In fact, it wasn’t until I heard a character refer to him as “Franz” that I recognized the film’s subject.

Inside Franz Kafka’s world

The story begins in 1923 when Franz, who is undergoing treatment for tuberculosis, visits his nieces and nephews at a nearby summer camp. A keen observer and storyteller, he watches Dora dancing on the beach with a friend, performing a dance he’s never seen before. The two quickly grow close, meeting after Shabbat, and Franz finds every opportunity to see her while she works at the summer camp nearby. But their budding romance is cut short when he is forced to return home with his family and Dora goes to live in Berlin at the Jewish community center with hers. Eventually, they are reunited when Franz moves to an apartment in Berlin, but living on his own for the first time proves to be a challenge with his fragile health.

The film’s audience is a bit unclear; those who are true fans of Kafka and his work may appreciate it as a biopic. However, the focus is not on “Kafka the writer” so much as it is on Franz the man — his struggles, his love, and his vulnerabilities. Rather, it’s an intimate portrait of Franz before he was known as Franz Kafka, and unless you care deeply about his history, this film may hold lesser significance.

Yet by emphasizing Franz as a person rather than an iconic writer, the film also allows Dora’s perspective to shine. Notably, Franz’s father, Hermann, is never seen, heard only by Franz and his sister in phone calls. However, his presence in his son’s life is very clear as Franz struggles to move away. When he shares his famous “Letter to his Father” with Dora, the depth of that fraught relationship becomes painfully clear, hinting at the themes that would later permeate his writing. Even in his physical absence, Hermann keeps his oppressive hold over Franz, and like Dora, the audience wishes he could fully get away from his grip. In contrast, Dora’s presence and care give Franz freedom. From visiting botanical gardens to teaching him about Judaism and Hebrew, her love seems to counteract his father’s shadow.

A story told through the senses

“The Glory of Life” succeeds in its sensory storytelling, capturing both the physical joys in Franz’s life. Dora’s scent becomes his primary connection to her, and even when he struggles to speak, he still breathes her in despite its difficulty. The film’s sound design plays with silence, a motif that mirrors Franz’s own reflections on writing — he believes he writes best in quiet.

Moments of solitude in his apartment are punctuated by the distant hum of street life, placing the audience in his shoes. In an awkward dinner scene with Dora and his sister Elli (Daniela Golpashin), the silence is made more uncomfortable with the clutter of forks on plates. Meanwhile, in voiceovers, Franz’s words take center stage, reminding us of the joy he found in putting pen to paper.

While obviously not intended by the filmmakers, the cold in the movie theater connected me to Franz attempting to stay warm in his bleak apartment. His room, cramped and dimly lit, feels disconnected from the outside world, and even his interactions are monitored by a nosy neighbor who disapproves of Dora’s visits. In contrast, the beach stands in to represent the warmth, the freedom, and the possibility that Franz and Dora feel when they first meet there.

One of the film’s most striking moments comes when Dora, searching for Franz in a Prague hospital, opens a door to find herself on the same beach, running across the sand in search of him. The golden sunlight gleams off the hospital beds, blending past and present in a moment that signals the loss of freedom. And yet, in a poignant scene set in the present day that starts the film, Dora finds the ribbon Franz once tied to a bench where they had shared a date. It’s a quiet reminder that their love still exists in that space, even in his absence.

The film falls short in its pacing. Like Franz’s tender condition, his relationship with Dora is similar and their love is tender, without a fight. This works in making the movie feel different, but it also didn’t make me feel enticed to watch. In fact, I found it to be a snoozefest at some points, struggling to stay awake as I knew their love would be short.

Still, the film is worth watching. Tambrea and Confurius deliver excellent performances, embodying the quiet devotion and tenderness of Franz and Dora’s relationship. “The Glory of Life” is, above all, a meditation on love and loss — one that resonates deeply in a world still grappling with illness and grief. It reminds us of the power of love, both in sickness and in health, and how, like Kafka’s words, the people we cherish continue to live on in our hearts and in the places they once inhabited.