On a chilly night in Toronto on November 1, 1946, the New York Knickerbockers tipped off against the Toronto Huskies in the very first game of what would become the NBA. Just minutes into the game, a Jewish guard from Brooklyn, Ossie Schectman, drove to the basket and laid the ball in. That shot — scored by the son of Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants — is remembered as the first basket in NBA history.

Long before basketball became a global, billion-dollar spectacle, it was something much humbler: a rough, fast, indoor game played in cramped urban gyms, settlement houses, and YMHAs. And for a few crucial decades, it wasn’t just a popular game among Jews — it was known as “the Jewish game.”

Historian Peter Levine wrote in “Ellis Island to Ebbets Field: Sport and the American Jewish Experience,” that “Jews have stereotypically been considered people of the book rather than people of the jump shot, right cross, or home run. Yet for many East European Jewish immigrants, and especially their children, participation in American sport during the first half of the twentieth century became an important part of their pursuit of the American dream and a pathway to assimilation.”

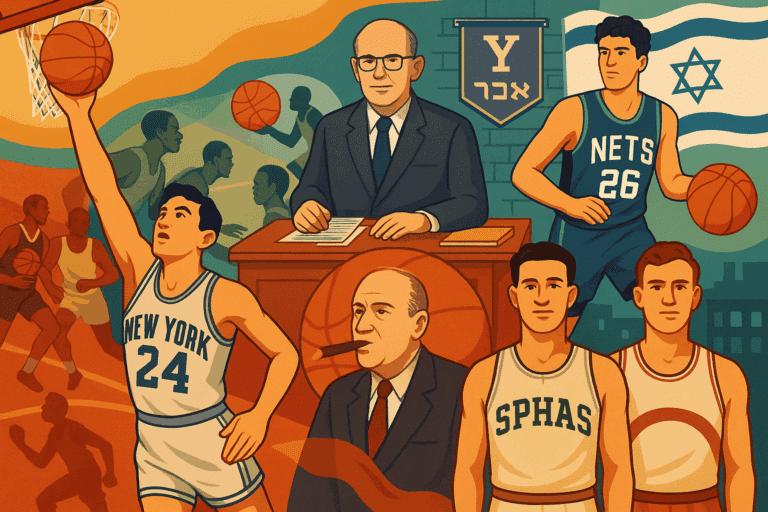

This is the story of how basketball helped Jewish immigrants become American, how Jewish players and executives helped shape the early pro game, and why that legacy still echoes every time a Jewish player steps onto an NBA court.

Basketball: A new game for a new kind of American

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe poured into American cities. They crowded into places like New York’s Lower East Side, Chicago’s West Side, Boston’s North End, and South Philadelphia. Apartments were packed, money was tight, and safe, affordable recreation was hard to find.

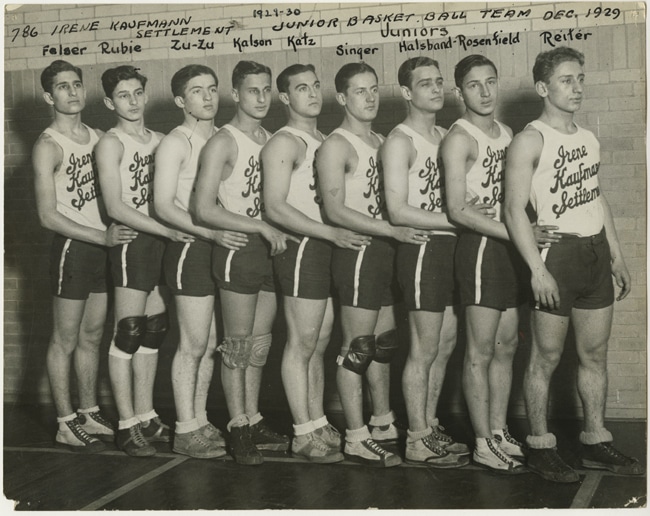

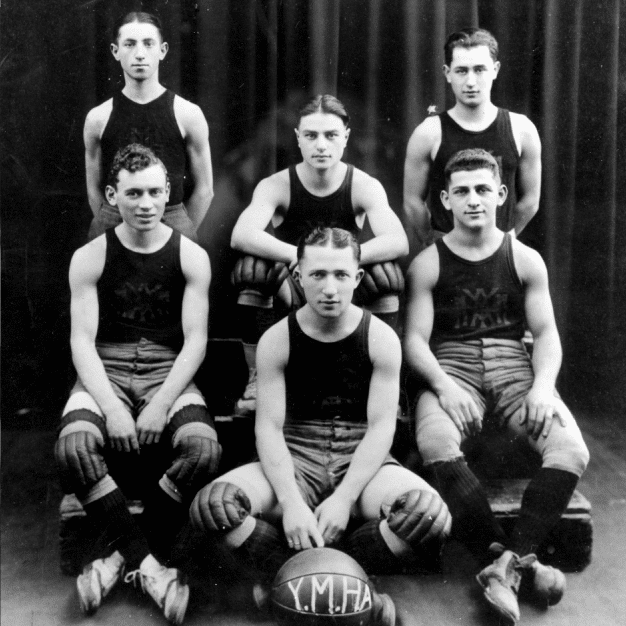

Around the same time, in 1891, Dr. James Naismith invented basketball at a YMCA in Springfield, Massachusetts, as an indoor winter sport that required little more than a ball, a couple of hoops, and a gym. The game spread quickly through YMCAs, settlement houses, and later YMHAs, the very institutions at the center of Jewish immigrant life.

Social reformers liked basketball because it kept kids off the streets and taught discipline and teamwork. For Jewish immigrants, it offered something more.

Basketball was cheap, and no equipment beyond sneakers and a ball was needed. It could be played indoors close to home, and it was meritocratic: you didn’t need height or lineage, just skill, hustle, and brains.

In crowded neighborhoods where Jews were often shut out of elite country clubs and college teams, basketball felt like a level playing field.

As historian Ari Sclar has argued in his work on Jews and American sports, this new athletic culture “provided Jews with opportunities to participate in one of the few American cultures not closed off to them.”

Playing “scientific basketball”

By the 1910s and 1920s, Jewish kids weren’t just playing pickup ball anymore; they were forming their own teams, leagues, and weekend tournaments in cities across the Northeast. Soon, they were playing on teams like the New York Whirlwinds, the Trenton Tigers, and the Philadelphia Warriors.

Because many Jewish players were shorter and less physically imposing than their opponents, they adapted the game to their strengths. They emphasized:

- Speed and cutting over brute force

- Crisp passing and spacing instead of one-on-one isolation

- Set plays and “brainwork” — reading defenses, anticipating rotations, and out-thinking the other team

Sportswriters at the time dubbed this style “scientific basketball.” It was seen as cerebral, strategic, and distinctly Jewish. Opponents might have had the size, but Jewish teams prided themselves on outsmarting them.

For Jewish fans, watching these teams win wasn’t just entertainment. It was a quiet rebuttal to antisemitism, proof that Jews could be tough, competitive, and as American as anyone else.

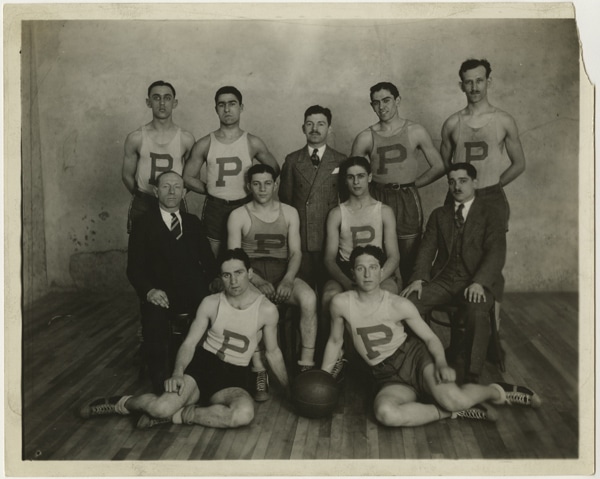

No team captured this era better than the SPHAS, named for the South Philadelphia Hebrew Association. Formed around 1917 by three Jewish teenagers, Eddie Gottlieb, Hughie Black, and Harry Passon, the SPHAS started as an all-Jewish semi-pro team sponsored by the local YMHA, which even helped buy their first uniforms.

They played home games in the ballroom of Philadelphia’s Broadwood Hotel, in front of rowdy, largely Jewish crowds. Their uniforms proudly featured Hebrew lettering across the chest.

Over the next few decades, the SPHAS became one of the dominant teams in early professional basketball, winning multiple titles in the American Basketball League (ABL), one of the sport’s first pro circuits.

At the center of it all was Gottlieb. A Ukrainian-Jewish immigrant who fell in love with the game as a teenager, Gottlieb wasn’t just the SPHAS’ coach. He scheduled games, handled travel, sold tickets, and negotiated with arena owners. His reputation for organization and business savvy earned him the nickname “the Mogul.”

Gottlieb’s identity as a Jewish immigrant shaped his vision. He once said: “Basketball is a game anyone can play — short or tall, rich or poor. That’s why it will last.” For immigrants like Gottlieb, basketball wasn’t just a sport — it was a metaphor for Jewish opportunity in the U.S.

Gottlieb and his players saw basketball as more than a pastime. It was a way to flaunt Jewish identity, and a way into mainstream American sports culture at a time when antisemitism was still widespread.

The 1920s also brought a rise in antisemitism on campus. Harvard’s president openly argued for Jewish quotas, including for the university’s athletic culture. As Columbia, Yale, Syracuse, and other schools debated and later instituted similar restrictions, pressure mounted from another direction: Yale alumni pushed coaches to drop discriminatory policies against Jewish basketball players if they wanted a competitive team. Jewish newspaper The American Hebrew noted that Yale’s embrace of Jewish athletes showed how success on the court could open doors, helping Jews gain acceptance on campus and easing their path to integration.

Besides facing discrimination and harsh anti-Jewish quotas, New York universities that fielded large Jewish teams became the pinnacle of college basketball.

In 1935, the New York Times wrote that the annual matchup between NYU and City College of New York had “never before … aroused such widespread interest,” as both teams came into the game undefeated and New Yorkers scrambled for tickets. The demand was so intense that promoters responded by launching regular college doubleheaders at Madison Square Garden the following season, briefly turning New York into the center of the basketball world. The following year, Newsweek ran a feature on the sport’s meteoric rise and flatly declared basketball a game “at which Jews excel.” In that NYU–CCNY showdown, nine of the 10 starters were Jewish — a snapshot of the era when Jewish players dominated the college game.

Building the NBA

As the game grew, Jewish figures were central to turning scattered regional leagues into a national enterprise.

In 1946, a group of hockey arena owners created the Basketball Association of America (BAA) to fill seats on non-hockey nights. The new league that would eventually merge with the National Basketball League to form the NBA in 1949. They chose Maurice Podoloff, a Jewish lawyer from New Haven, Connecticut, as the BAA’s first president — and later the NBA’s first commissioner.

Podoloff wasn’t a former star player or coach. He was simply an administrator with a law degree and a reputation for fairness. He oversaw the merger of the BAA and NBL into the NBA in 1949, helped expand the league and stabilize struggling franchises, and introduced innovations like the college draft and later the 24-second shot clock, which sped up the game and made it more exciting for fans

With the creation of the NBA, the era of the Jewish basketball star began to wane. For many Jewish players of that era, pro ball was still essentially a side job — they worked full-time in other professions and played semi-professionally on the side. Very few could afford to stay in the league long term because basketball salaries weren’t enough to sustain a family.

At the same time, rising socioeconomic success pulled many Jews out of the urban neighborhoods where the game had first taken root. As families moved to the suburbs and found new avenues into mainstream American life, sports were no longer the primary route to acceptance. Jews still played basketball, but now it was more likely in suburban gyms and JCCs than on cramped city courts.

Still, for the Jewish players who chose to pursue professional basketball, they began making history. When Ossie Schectman scored that opening basket for the Knicks against the Huskies in 1946, he wasn’t just putting up the first points in league history. He was symbolically carrying the game from the immigrant gyms of the Northeast into a new, national spotlight.

Schectman had honed his game with the SPHAS and at NYU before making the Knicks roster. His moment on that November night connected the Jewish “Y” leagues and the brand-new professional league in a single layup.

Historian John Thorn noted that seven of the ten original Knicks were Jews, a reminder that the league’s very first New York team looked a lot like the Jewish playgrounds and YMHAs it drew from.

Gottlieb, meanwhile, moved from the SPHAS into NBA ownership, becoming the first owner of the Philadelphia Warriors and bringing some of his Jewish stars with him.

Red Auerbach, Jewish coaching culture, and the decline of Jewish athletes

If Podoloff helped shape the league from the front office, another Jewish figure helped define what winning basketball would look like on the court: Red Auerbach.

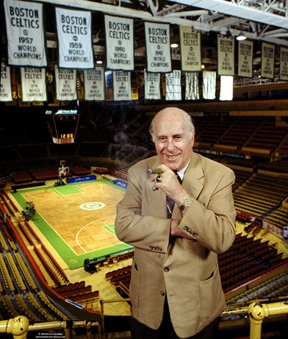

Born Arnold Jacob Auerbach in Brooklyn to Russian-Jewish immigrants, Red became the legendary coach and general manager of the Boston Celtics. From 1950 to 1966, he led the team to nine NBA championships — eight of them in a row — creating the first NBA dynasty.

But Auerbach’s impact wasn’t just about rings. He was years ahead of the rest of the league when it came to racial integration and opportunity. Auerbach’s approach was shaped in part by his own background. Growing up as the son of Jewish immigrants in a working-class Brooklyn neighborhood, he knew what it meant to be an outsider and to hear slurs thrown his way.

He drafted and traded for Black stars when other teams hesitated. On Dec. 26, 1964, he sent out the first all-Black starting lineup in NBA history — Bill Russell, K.C. Jones, Sam Jones, Tom “Satch” Sanders, and Willie Naulls — ignoring the unwritten rule that there always had to be at least one white player on the floor. When Auerbach stepped down as coach in 1966, he named Bill Russell his successor, making Russell the first Black head coach in major American professional sports.

Auerbach was famously tough, competitive, and blunt, but he saw his Jewishness and his belief in fairness as intertwined. In a league still grappling with racism and prejudice, his choices — who he trusted, who he put on the floor, who he handed the team to — helped change the culture.

A handful of standout Jewish players, like Lennie Rosenbluth and Art Heyman in the 1950s and 1960s, still reached the top levels of the game. But from the early 1970s on, Jews have been far more visible in basketball’s front offices and on the sidelines than on the floor itself — as coaches, executives, and owners. Hall of Famer Larry Brown, longtime NBA commissioner David Stern, Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, and former player–turned–general manager Ernie Grunfeld are just a few of the Jewish figures who have helped shape modern basketball from behind the scenes.

Jews and the NBA today

As the NBA grew and the Jewish population moved to the suburbs, the game stopped being seen as a “Jewish sport” in the same way. Jewish players became less common in the league, even as Jews remained visible as owners, executives, agents, and superfans.

Still, the legacy never completely disappeared. Omri Casspi’s 2009 debut with the Sacramento Kings made him the first Israeli to play in the NBA, inspiring a generation of Israeli kids to dream about following him.

In the 2010s and 2020s, more Israelis joined him, including Deni Avdija, who became a key forward and one of the most visible Israeli faces in the league.

Then, in June 2025, the Brooklyn Nets made history when they drafted two Jewish players back-to-back in the first round: Israeli guard Ben Saraf at No. 26 and American-Israeli big man Danny Wolf at No. 27. For the first time, two Israeli players joined the same NBA team. Together with Avdija, they gave the league three active Israelis at once, a milestone unthinkable back when Jewish kids were sneaking in games between shifts in the garment factories.

Off the court, Amar’e Stoudemire — the former NBA All-Star who later became an Israeli citizen and played for Hapoel Jerusalem and Maccabi Tel Aviv — was selected for induction into the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame’s 2025 class, symbolizing this new, global chapter of Jewish basketball.

While men’s professional basketball stopped being seen as a distinctly “Jewish game” after the mid-century, Jewish presence has remained more visible on the women’s side. In the WNBA, Jewish and Israeli players like Sue Bird, a 12-time All-Star and four-time champion, have become some of the most decorated athletes in league history. Bird, who has spoken openly about her Jewish identity, helped turn the Seattle Storm into a dynasty and became a global face of the women’s game. Other Jewish and Israeli players have followed her into the WNBA and European leagues, extending the story of Jewish basketball into women’s sports and showing that the legacy of “Jewish hoops” isn’t confined to the NBA.

Basketball looks very different today than it did in the days of the SPHAS or Red Auerbach’s Celtics. The league is global, the players are taller and stronger, and the money is astronomical.

But the core of what once made it “the Jewish game” is still there. It remains a sport where intelligence and teamwork can trump raw power. For outsiders — immigrants, minorities, and kids from the margins — basketball still is a pathway to rewrite how the world sees them.

From Schectman’s first basket to Podoloff’s boardroom, from Gottlieb’s Hebrew-lettered uniforms to Saraf and Wolf in Brooklyn, Jews have helped shape basketball — and basketball, in turn, has helped shape what it means to be Jewish and American.

The old YMHAs and hotel ballrooms may be gone, but every time a Jewish or Israeli player checks into an NBA game, they’re adding another chapter to a story that began in those crowded immigrant neighborhoods more than a century ago.