Each year, many of us sit at the Passover table with a mix of curiosity and uncertainty — not fully knowing the traditions, unsure of what exactly comes next. But the Seder is more than just an ancient script; it’s an invitation into a living experience, helping us find personal meaning in stories from the past. The Seder goes beyond memory, drawing us into a dynamic narrative where past and present seamlessly intertwine.

What if the most profound insight of Passover isn’t the triumph of liberation itself, but rather the recognition that freedom isn’t a destination reached once and for all? Our ancestors didn’t simply cross the Red Sea to live happily ever after. They wandered, complained, yearned for the familiar discomforts of Egypt, celebrated moments of transcendence, and descended again into fear and doubt — often within the span of a single day.

Sound familiar?

The Seder openly acknowledges this emotional complexity and invites us to explore it deeply. Through each symbolic food, we’re encouraged not just to remember history, but to discover personal connections and reflections in our own experiences. Every item on the Seder plate becomes a chance to see ourselves more clearly.

Let’s begin with the first: a small, green sprig that carries the weight of contradiction.

Karpas: Renewal swimming in reflection

We begin with fresh greens dipped in saltwater — spring’s promise immediately submerged in tears. This juxtaposition profoundly mirrors our lived experience.

Remember the promotion you celebrated, only to awaken the next day anxious about new responsibilities? Or that relationship milestone shadowed by echoes of past heartbreak? Karpas whispers a truth we often deny: renewal and reflection aren’t sequential stages, but rather simultaneous experiences.

“The world breaks everyone,” Ernest Hemingway wrote, “and afterward, some are strong at the broken places.”

This idea resonates deeply with why we break the middle matzah during the Seder — it symbolizes that acknowledging our brokenness is an essential step toward becoming stronger and freer. Liberation begins when we lean into our pain, not away from it.

As communities, we know this intimately. Even amid progress, we carry historical wounds — civil rights gained alongside persistent injustices, medical breakthroughs tempered by ongoing suffering. Karpas teaches us that this coexistence isn’t a contradiction — it’s completeness.

Maror: Returning unexpectedly to bitterness

Just when we think we’ve moved beyond bitterness, the Seder directs us back to maror — the bitter herbs, typically horseradish or romaine lettuce, traditionally symbolizing the harshness of slavery. Its sharp taste vividly reminds us of pain endured long ago. How inconvenient — and how honest.

“Why must we taste the bitter herbs twice?” a student once asked.

“Because,” I replied, “have you ever known suffering to politely excuse itself after one appearance?”

Think of a personal struggle — an insecurity, a harmful pattern, a lingering fear — you believed you’d overcome, only to have it return months or years later, cleverly disguised until you’re already ensnared. Maror reminds us: liberation isn’t a singular event but an ongoing practice.

Collectively, we revisit bitterness repeatedly. Societies confront the same challenges generation after generation, often convinced “this time, we’ve solved it.” Maror smiles gently at our optimism, not to discourage, but to prepare us for freedom’s continuous labor.

Charoset: Sweetness amid struggle

One of the Seder’s most profound paradoxes is charoset — a sweet, textured mixture often made from apples, nuts, cinnamon, and wine. Despite its sweetness, charoset represents the mortar our ancestors used in Egyptian slavery. The architects of the Seder understood that even our hardest moments hold sweetness — friendships forged through adversity, self-discovery through hardship, and community bonds strengthened by shared struggle.

A Hasidic tale tells of a man who complained to his rabbi about his difficult life. The rabbi replied, “If you placed your troubles in a sack and then saw everyone else’s, you’d swiftly reclaim your own.” Charoset invites us to discover sweetness hidden within our unique struggles.

Communities know this intimately. Adversity becomes the mortar that binds: Neighborhoods finding their voice through shared challenges, unexpected alliances emerging against common threats, innovations arising from necessity.

Zeroa: The unfinished sacrifice of identity

The shank bone (zeroa), typically a roasted lamb shank or chicken bone, symbolizes the Passover sacrifice. More deeply, it represents the ongoing sacrifices we make in our lives — not just historical rituals, but the continual letting go and transformation that growth demands.

Freedom demands sacrifice. Comfortable identities, familiar narratives, cherished certainties, all must be relinquished on the altar of becoming. Zeroa acknowledges this ongoing offering each time we choose liberation over confinement.

“And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom,” wrote French essayist Anaïs Nin. Passover invites similar reflection — not just on leaving Egypt, but on whether we are willing to leave behind what constrains us now.

In Hebrew, the word for Egypt, Mitzrayim, shares a root with meitzar, meaning “narrow” or “constricted.” It’s a poetic reminder that Egypt is not only a place on a map — it’s any state of being that confines us. The question the Seder poses is not only, “Did we leave Egypt?” but, “Are we still living in a narrow place?” And more importantly, “Are we ready to step out of it?”

Communities also make continual sacrifices. Traditions evolve, leadership shifts, spaces transform — yet core identities endure. Zeroa prompts us to ask: What must we continually relinquish for collective becoming?

Beitzah: Cycles and the cosmic comedy

If the Seder had a punchline, it would be the beitzah — a roasted egg symbolizing both mourning and fertility, endings and beginnings. Its perfect oval hints at the cycle of life, the cosmic irony of returning from where we started, albeit with better questions.

Remember when you believed, “Once I achieve this, I’ll have arrived,” only to face a new horizon? Or declared, “I’ve finally outgrown this pattern,” right before repeating it? The egg nods sympathetically, offering a wry smile at our human predicament.

My grandmother, witness to countless historical cycles, used to say, “Just when you think you’ve seen the final act, they change the costumes and begin again.” Yet each year, she meticulously set her Seder table — quietly testifying to the meaning found within cycles, not beyond them.

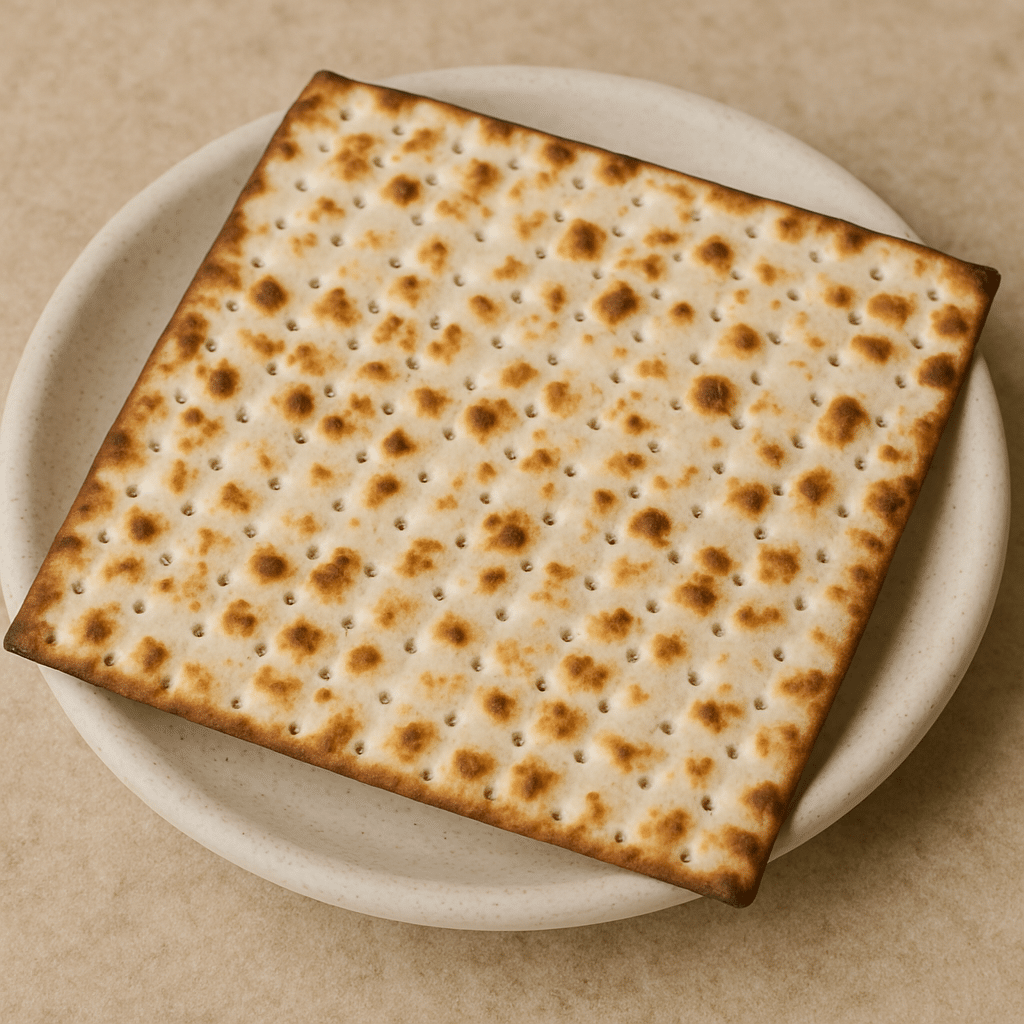

Matzah: Humility’s authentic freedom

Behold matzah: flour, water, and humility, that’s been hastily prepared without pretense. Paradoxically, our most rushed, unfinished moments often reveal our truest selves.

When life accelerates and there’s no time to present perfected versions of ourselves, authenticity comes through. Matzah celebrates the unadorned self, unenhanced and unconcealed.

“Leavened bread rises as if showing off,” noted 16th century Rabbi Yehuda Lowe of Prague. But we know that the flat bread of authenticity is so much more fulfilling.

Communities, too, find liberation in simplicity. In times of turmoil, we return to fundamental values, essential questions, and core relationships — matzah moments, when pretense fades and genuine purpose emerges.

Four cups of wine and Elijah’s Cup: Freedom’s punctuated equilibrium

We drink four cups to mark stages of liberation. Elijah’s untouched cup symbolizes our hope for future redemption — a cup symbolically waiting for the prophet Elijah, said to herald a time of universal peace.

This choreography mirrors life’s rhythm: partial victories and persistent anticipation.

Consider celebrating achievements while glancing anxiously at other unmet goals, or focusing so deeply on what’s lacking that current triumphs go unnoticed. The Seder visually reminds us of this perpetual tension, encouraging us to honor both.

Our cups have often overflowed, yet there are also moments when they’ve run dry — and that’s perfectly normal. Passover invites us to hold space for these moments, wisely celebrating victories even as we acknowledge ongoing dreams and unmet hopes.

Personalizing your non-linear journey

As you approach your Seder this year, consider these prompts for reflection:

- Where are renewal (karpas) and bitterness (maror) simultaneously present in your life?

- What sweetness (charoset) has emerged from your struggles?

- Which parts of your identity (zeroa) are transforming through ongoing sacrifices?

- What recurring cycles (beitzah) do you notice in your personal or communal life?

- How has simplicity or urgency (matzah) revealed authenticity?

- Which cups of liberation have you filled, and which remain to be poured?

These questions invite us to embrace the complexity of human experience. The Haggadah reminds us: “In every generation, each person must see themselves as personally leaving Egypt.”

Not “having left,” but continuously leaving — a perpetual journey of becoming.

The Beautiful Complexity of Freedom

Perhaps Passover’s most radical teaching is this: liberation isn’t achieved, but practiced. We don’t cross the Red Sea once; we learn to navigate its rhythmic tides. Sometimes we stand on dry land, amazed at our open path before us. Other times, waters threaten to close in. Both experiences are integral to the journey.

“Freedom,” philosopher Albert Camus wrote, “is nothing but a chance to be better.” The Seder adds: “and that chance recurs, as reliably as spring itself.”

Let us gather at our tables — traditional or reimagined — and honor freedom’s complexity. Embracing liberation’s non-linearity is, paradoxically, what sets us free.

There’s an old joke that the real miracle of Passover isn’t the parting of the Red Sea, but that families can survive four hours around the dinner table. May your Seder remind you that the journey, with all its twists and lengthy family discussions, is the destination we’ve been seeking all along.