This year, the Oscars for both Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor were awarded for performances in movies about the Holocaust. While the films were incredibly different — “The Brutalist” focused on a Holocaust survivor and Brutalist architect who immigrates to the United States after the Shoah, while “A Real Pain” told a story of two cousins taking a tour of Poland, where their Holocaust survivor grandmother grew up — their success during awards season was undeniable. This is not a new phenomenon. Films about the Holocaust, such as “Schindler’s List” or “The Zone of Interest,” are often awarded by Hollywood elite.

Holocaust movies are films of Jewish pain

Like many of my Jewish peers, I know about the Holocaust. I do not have any direct survivors in my family, but around 1 in 10 American Jews do. I have been to the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. and to Yad Vashem in Israel. During my senior year of high school, I participated in The March of the Living and spent time in Poland visiting places like the Warsaw ghetto, Auschwitz, and Majdanek. So why am I so tired of Holocaust movies?

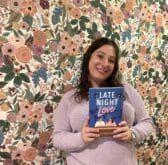

The simple answer is that I tend to prefer stories of Jewish Joy. Since publishing my own Jewish romance novel February 2024, I have been more enmeshed in the world of Jewish stories than ever. While some of them involve antisemitism, most don’t. My novel, “Late Night Love,” is full of Jewish humor that often involves mocking modern Jew hatred. When I go to read a book, watch a movie, or binge a TV show, I’m usually searching for content that celebrates the joy of being Jewish instead of focusing on our past oppression.

The more complicated answer is tied to one crucial part of that sentence: the past. When most of the serious Jewish representation is about the Holocaust, it can unintentionally perpetuate a narrative that antisemitism is confined to the past, not the present.

Creating media that reflects today’s Jews

The events of the Shoah happened less than a century ago, but the world has changed quite a bit since then. Setting a majority of stories about the Jewish people against the backdrop of a time without smartphones or the internet can make it easy to imagine that such vile, barbaric Jew hatred has no place in our modern society.

Unfortunately, that couldn’t be further from the truth. The violently antisemitic terrorist groups that attacked Israel on Oct. 7 committed the largest mass murder of Jews since the Holocaust. They slaughtered joyfully and indiscriminately. A particularly haunting phone call that I heard in the Nova Exhibition, named for the Nova musical festival where one of the largest attacks was carried out, involved a Hamas terrorist bragging to his father about how many Jews he had killed.

The nightmare has not ended in the days since. Hamas still holds innocent Jews and Israelis hostage. Across the diaspora, Oct. 7 was celebrated by communities that claim to advocate for justice under the guise of legitimate resistance. Antisemitism has soared, and yet Jews are being told that it hasn’t, because it now wears a clever new disguise: anti-Zionism. The vast majority of Jews are Zionists, with any differentiation between the two identities belonging to a small but very vocal portion of anti-Zionist Jews who have been used to legitimize this modern evolution of the same hate that caused the Holocaust.

In an article for The Atlantic, novelist Dara Horn argued that when Holocaust education failed to discuss contemporary Jews, it could be making antisemitism worse.

“If we teach that the Holocaust happened because people weren’t nice enough — that they failed to appreciate that humans are all the same, for instance, or to build a just society — we create the self-congratulatory space where anti-Semitism grows,” Horn writes.

Holocaust education is not the solution to antisemitism

This attempt to use the Holocaust to teach morality or tolerance often fails because, while focusing on the reality that Jews are indeed human, it ignores how the actual practice of being a Jewish person makes a Jew fundamentally different from most of the world.

When modern Holocaust education focuses only on the dead Jews of the past, it does not do enough to combat modern antisemitism because it doesn’t help students understand the Jewish people. One docent Horn interviewed said many students ask her if there are any Jews still alive today. Horn writes that she is not surprised by the question, when so many of these museums and pieces of curriculum end by segueing to other genocides or the suffering of other minorities. That is not to say that such topics are not important, but they reinforce a false narrative that antisemitism is no longer something of concern. “It is dehumanizing to be treated as a symbol. It is even more dehumanizing to be treated as a warning.” A 2014 Anti Defamation League survey of people from 100 countries revealed that 74% of respondents had never met a Jewish person. If all these people who have never met a living, breathing Jew know are the images and lessons of the Holocaust, can they ever truly understand why it happened?

I would like to make it clear that I am not arguing against narratives about the Shoah (unless those narratives involve non-Jews exploiting our generational trauma, in which case I am very much against them). But I do think it is dangerous and unhelpful when these are the only, or at least the most prevalent, Jewish stories.

To paraphrase something the incomparable Jean Meltzer has said, why is it that when people think of a Jewish book, the first thing that comes to mind is a book about the Holocaust? The Jewish people are more than that. We deserve more. For the People of the Book, as Jews are often known, the Holocaust is only one devastating chapter of our past and present. It’s an important one. But the Jewish people are more than our trauma. I think it is time that our narratives on page and screen alike start to reflect that.

Originally Published Apr 16, 2025 02:03PM EDT