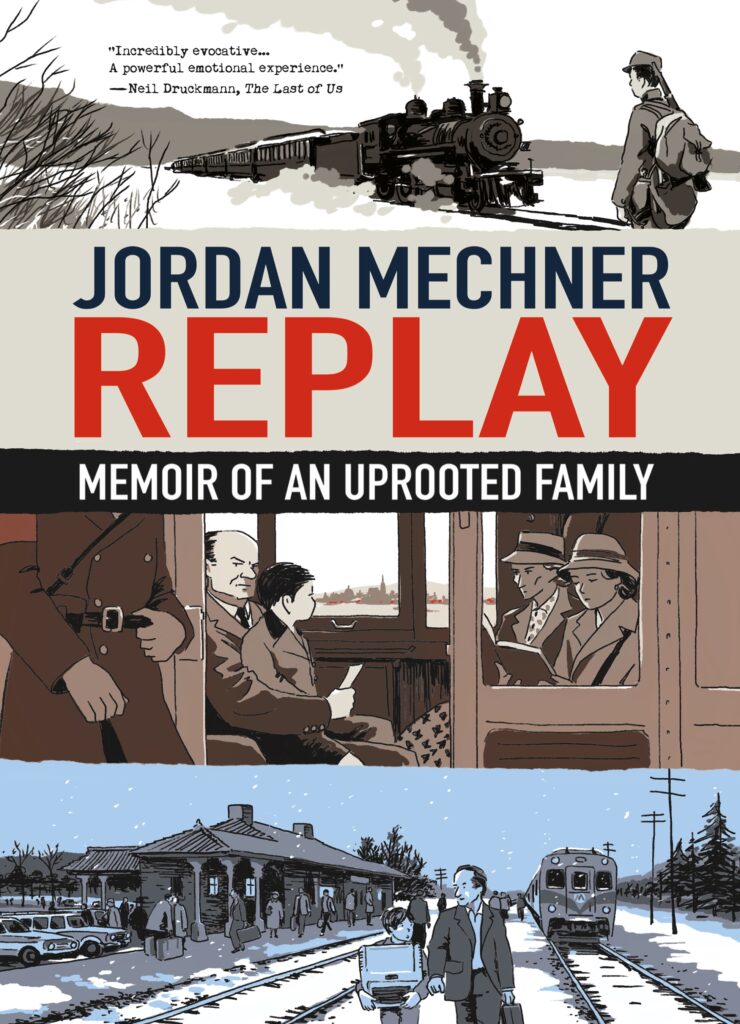

Before Jordan Mechner became known as the visionary creator of “Prince of Persia,” he was a kid growing up in New York — safe, free, and unknowingly shaped by the incredible, harrowing story of how his Jewish family escaped Nazi-occupied Europe. In his graphic memoir “Replay: Memoir of an Uprooted Family,” Mechner trades fictional adventures for something much closer to home: the true story of his father and grandparents’ flight from Vienna during World War II, and the generational echoes that shaped his own life decades later.

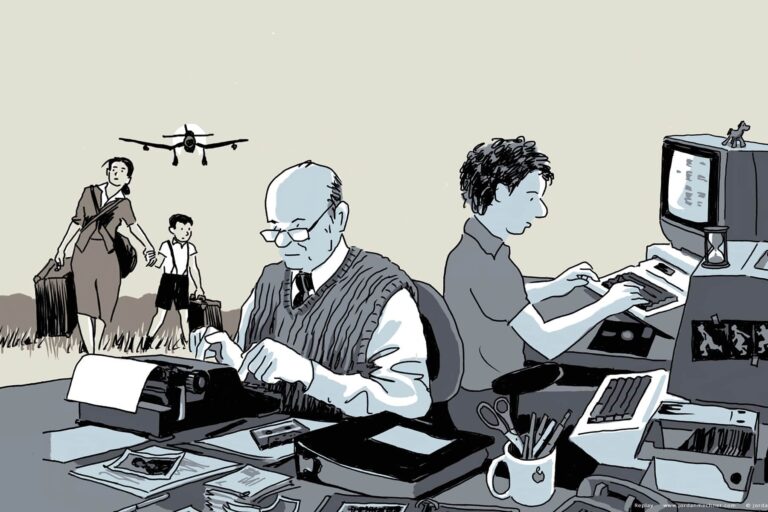

Told through hand-drawn panels that Mechner illustrated himself, “Replay” braids three timelines — his grandfather’s experience in World War I, his father’s childhood in occupied France, and his own career in video games — into one deeply personal narrative about memory, inheritance, and identity.

Unpacked chatted with Jordan Mechner about the decades-long journey to bring “Replay” to life, the research work behind tracking down long-lost family details, and how telling his family’s story helped him better understand his own.

Read more: Unpacked’s top 18 Jewish book picks for 2025

What initially made you interested in telling your family’s story?

Like a lot of second-generation immigrants, children of Holocaust survivors, I grew up hearing these incredible stories of the previous generation’s escape from Europe during World War II, and I wanted to put that story into form.

I’m a storyteller, through video games like “Prince of Persia,” film screenwriting, and graphic novels. I had written fictional stories, but this was the first time that I told a story that was so personal and that was true. I had the great gift that my father and grandparents were very willing to share their story. My grandfather, even when he retired as a doctor in Brooklyn in the 1970s, spent three years compiling a family memoir. He wrote down his memories of being a soldier on the Russian front in World War I, and the details of the family’s flight from Vienna in 1938 as Jewish refugees, and how my dad got stuck in occupied France with his young Aunt for three years from ages seven to 10 during the German occupation.

So I had all their stories to draw from. And so delving into the research to write and draw “Replay,” a graphic memoir, was a way for me to engage with the heritage that they had passed down to me and, in drawing from them to, come closer to them, to understand better what they had experienced, and also to relate it to my own very different life as an American kid growing up safe and secure in New York and having a chance to devote my time to comics and video games thanks to the risks they had taken and their survival.

And why were those parallels an important part of telling the story? Why did you think it was the most effective way of storytelling, instead of just talking about your grandfather and father’s experiences?

At first, I thought that “Replay” was going to have to be three books, that I would do a book about my grandfather’s experience growing up in Czernowitz and being drafted into the army in World War I, and then a second book about my father’s experience as a child refugee in France in World War II, and then a third book about me making video games in the 1980s and 90s.

I just couldn’t find a way to make those three things fit together. What made the structure of “Replay” click into place was when my French editor, Louis Trondheim, remarked that by moving to France with my two teenage kids in 2016, I had basically done the inverse of what my grandfather had done, fleeing from Austria in 1938. Like him, I had separated my two kids from each other for a period to bring the family back together on the other side of the Atlantic. Of course, the similarity ended there, because they were fleeing to save their lives, and I was moving for a professional opportunity to lead a wonderful video game project in Montpellier — vastly better circumstances.

But that theme of a mirror image and of a younger generation kind of repeating a pattern of the past unconsciously gave me the structure of the book and the title of “Replay,” which is, of course, what you do in a video game, replaying the same level as many times as you need to until you get it right and succeed. So, “Replay” was the theme of the book, both through video games and through this sense of repetition, that sometimes the uncanny way the past is present, even when we don’t consciously realize that it is.

What was the research process like for “Replay”? You had the memoir, and your father was open to talking, but did you have to delve deeper into your family’s history?

My dad has an amazing memory, but he experienced these events through the point of view of a child. So, a lot of times there were in order to depict and draw these events, I needed a fuller perspective. So I did research by reading as much as I could, by watching documentaries, looking at newsreel footage and photographs, and other people’s memoirs from the time. I made a road trip down the Atlantic coast of France to visit the towns where my dad and his aunt had stayed during their flights from the Gestapo in 1940 and 41.

I visited Le Touquet, which was a seaside town in northern France, where my dad’s parents left him, thinking he would be safe. But of course, the German invasion in May 1943, already changed everything, and my dad and his aunt found themselves in a war zone. So I visited both to see the place and also to research the very specific history of that town, so and so in Montreuil-sur-Mer, and then finally, in Nice.

I needed to spend time there to get a sense for the feeling of the town, and also to to understand the context of what life there had been like during the particular phases of the war and the occupation when my dad had been there. I was lucky in every town to find historians and local archivists who had preserved the memory of that period, and in many cases, were able to come up with incredible details that I never would have imagined could still be found so many years later.

To take just one example, my dad and his aunt fled from Le Touquet in 1940 and took refuge in a small fishing village on the Atlantic coast of France. He had told me about the house that they stayed in and the French family that took them in for the three months. He spent three months basically playing on a strip of beach because it was too dangerous for him to go to school or to go out to town. I didn’t imagine that there would be any trace of this house in such a remote location, but unbelievably, I was able to find the actual house that my dad had stayed in and even found a photograph of the house in the 1900s as it had looked then. So I was able to visit and look at the house and look down on the exact strip of beach where my dad had spent two months in 1940.

Were there more times throughout the process that you just uncovered more of the family story as you delved deeper?

In many cases in the course of my research, I uncovered details that my family hadn’t known. One family legend that I had heard as a kid was that my dad and his parents were able to escape from Vienna in 1938 at a time when it was so difficult for Jews to get visas, thanks to an uncle. My dad’s uncle, Joseph, had found in his basement two watercolors that he had bought before the war, and noticed that they were signed Adolf Hitler, and he had and that he had been able to trade these watercolors to a Nazi official for visas to get his family out of France and and then to get tickets for my dad and my grandfather to follow him. So I researched this to make sure that it was true.

I was able to find in a book about Hitler’s youth that before World War One, Hitler had been an artist in Vienna and painted watercolors of Vienna’s buildings and tourist attractions, and sold them to a local frame shop. The frame shop owner had told his story, and my dad’s uncle, Joseph, was actually listed in a footnote in the book as one of the clients. He had told his story when he was being questioned to leave the country, and the writer of this book had transcribed part of his answers. So this confirmed the story, but gave me many details that Uncle Joseph had never shared with the family.

So much of your work, whether it’s a video game or your graphic novels, has been rooted in the past. Was the research process different for looking into your own story and your family story?

In all my work before “Replay” and all of my other projects, including the video games like “Prince of Persia,” “The Last Express,” and graphic novels like “Monte Cristo” and “Templar” I’ve always enjoyed the research process. But a first step to those projects was creating a fictional narrative set in that world, the details of a time and place, whether the Orient Express in 1914, or ninth-century Persia. I’m going to create characters and an adventure story that I want to feel real, but I give myself the freedom to invent. With “Replay,” I really wanted to stick to the truth and not do a Hollywood treatment that would make the story seem more exciting, or not tug at the heartstrings.

What continues to ground your work so much in the past? What interests you about telling those stories?

I think, as a reader and as an audience member, I’ve always enjoyed stories that are set in other times and places. It’s a way to travel and a way in imagination and a way to learn about times and places that I haven’t experienced myself. As an author, the reason to tell us to set a story in the past is a way to write about things that are relevant to today. Sometimes when, when we’re in the midst of events, it’s it’s hard to see the forest for the trees, but by reading about events that happened long ago or far away, we see a reflection of things that are happening right now, and that gives us the key that we need to connect to these events differently, and perhaps even to learn from the past.

“Replay” is the first of your graphic novels that you illustrated yourself. What does it mean to you to truly take control of that aspect of the story?

In my previous graphic novels, “Templar” and “Monte Cristo,” I worked as a writer with wonderful illustrators. I used to draw when I was a kid. If personal computers and video games hadn’t been invented when they were, I think I might have continued writing and drawing comics. My childhood dream was to be an artist for Mad Magazine in the 1970s, so in a way, I came full circle to one of my first childhood passions. Working with great artists as a video game designer and as a writer over the years has really reawakened the desire to draw myself.

It was about 15 years ago when I wrote “Templar,” illustrated by LeUyen Pham and Alex Puvilland. I started sketching again as a hobby. I saw Alex’s sketchbook, and that just seemed great to me. So I started carrying a Moleskine sketchbook around with me and drawing people in cafes, at airports, in the game development studio, drawing my kids, and members of my family. I didn’t have the ambition that one day I’m going to draw my own graphic novel. But you do something every day for 15 years, and at a certain point, you realize it’s become more than just a hobby. It’s something serious. And for me, you know, the idea of “Replay” came at just about the point when I felt that my drawing had brought me to the point where I was ready to write and draw in a graphic novel. “Replay,” because it was so personal, because I would need to portray the people in places that I knew best, that I had experienced, I felt that this was the right book for me to draw as well as write.

And why do you think it’s important to continue telling stories about the Jewish experience in World War II?

I think the experience of seeing the place that you live become dangerous to the point that you have to flee for your life, the experience of being persecuted, having your town bombarded, is universal. It’s, unfortunately, something that’s still going on today in many parts of the world. The details of everyone’s experience are specific, but the feeling of being afraid for your life, of being separated from your family, of having to leave the place that you love and start over in a new place that’s inhospitable, where you don’t speak the language is something that other people can connect to, and that can help us have empathy.

What do you hope readers gain from reading “Replay?”

One of the most moving things that I hear from readers when they’ve taken after reading “Replay” is that it’s made them think about their own family. Many readers said it brought them together in a conversation or a connection, or gave them the desire to speak to their parents or grandparents to learn more about where they came from and their experiences. Our stories can be a bridge between generations. And so if reading about someone else’s story can inspire people to connect more deeply with their own family stories, that’s the greatest response that I could wish for.