The Israeli-Palestinian conflict isn’t just about borders or resources; it’s also a fight between historical narratives.

Nowhere is that clearer than in Hebron, a city packed with history, religion, and conflict.

Abraham in Hebron

The conflict surrounding Hebron can be traced back to one man: Abraham.

Both Israelis and Palestinians trace their origins to Abraham. The Jews call him Avraham Avinu (Abraham, our forefather), while Muslims call him Ibrahim and Khalilullah (the friend of God).

Hebron’s sacred history starts with Abraham. While the city is referenced over 87 times in the Hebrew Bible, its seventh appearance is where our story starts.

In that story, Abraham pays 400 silver shekels to a local named Ephron for a plot of land where he could bury his wife, Sarah. This piece of land – known as the Cave of the Patriarchs in English, Maarat Hamachpela in Hebrew, and al-Haram al-Ibrahimi (the Sanctuary of Abraham) in Arabic – is where he and the rest of his family, the other forefathers and foremothers of Judaism, would be buried.

For centuries, the tomb was essentially just a cave, but about 2,000 years ago, the Jewish King Herod built a massive structure around it, with its roof open to the sky.

As the two other Abrahamic religions, Christianity and Islam, emerged, they claimed Abraham and his final resting place as their own.

When Christianity became the dominant religion of the Byzantine Empire, which ruled the region, part of the tomb was converted into a church, although Jews were still allowed to worship there. After the Arab conquest of the region, the site was converted into a mosque.

“This region thinks historically; this region thinks religiously,” explained Yishai Fleisher, the international spokesperson of the Jewish community in Hebron. “It’s important to people: Who was Abraham? It’s important to them that they’re related to Abraham. It’s important to them that they administer the tomb of Abraham. In Jerusalem, the question is, who does God favor? Whose God reigns supreme in Jerusalem? The Muslim God or the Jewish God? And here [in Hebron] it’s, who is the chosen son of Abraham?”

For years, while the site changed hands between Christians and Muslims, Jews were still allowed to worship there. But in 1267, the Mamluks, a new Muslim empire, took over and banned entry to Jews, allowing them only to approach the seventh step leading to one of the entrances.

For the next 700 years, the Jewish community in Hebron remained small, poor, and pious, living as second-class citizens among their Muslim neighbors.

Everything changed, though, after World War I.

How a political conflict turned religious

The Ottoman Empire, which had ruled the region for centuries, was gone. The British and French began divvying up the area for themselves.

The British made vague and ambiguous promises to both the Arabs and the Jews of the region. They promised the Arabs a self-governing state, while simultaneously promising the Jews a “national home in Palestine.” In the meantime, Jewish immigrants poured into the region, buying up land and building new towns and cities, alarming Arab residents.

Despite rising tensions, Hebron remained relatively quiet through the 1920s, although the situation was far from great.

“There’s this myth that the relationship between Jews and Arabs was so good. When you zoom in closer, things look different. There were a lot of challenges,” explained Tzippi Shlissel, an Israeli resident of Hebron with deep roots in the city.

For centuries, Jews had been a minority in their own homeland, subject to the whims of their neighbors and local leaders. That meant they had little protection from persecution.

Political Zionism changed that reality, encouraging Jews around the world to take their fate into their own hands by establishing a Jewish state with an army to defend itself. In the 1920s, though, Hebron’s Jews weren’t political Zionists. For them, protection came from God, not a government or army.

In 1929, disaster struck. The entire Jewish population of Hebron was either killed or forced to flee.

The massacre was pushed by Hajj Amin al-Husayni. Descending from a long line of religious and civil leaders in Jerusalem,Husayni was the first major figure in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to braid religion and nationalist violence together. His family was influential, so the British understood that if they wanted to keep the peace, they’d need to stay on their good side.

To achieve that goal, the British decided to give Husayni more power, even after trying to arrest him for inciting violence against Jews. Husayni was given the title of Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, and he was given control of a new Supreme Muslim Council.

Husayni used his new power to incite a religious war. In 1928, he started a rumor that still shapes the conflict to this day: that the Jews were plotting to destroy the Al-Aqsa Mosque to rebuild the ancient Jewish Temple on the Temple Mount.

The Temple Mount and Al-Aqsa Mosque are in Jerusalem, not Hebron. Israel’s capital city is another city filled with both sacred sites and conflicts. Two Jewish Temples once sat on the Temple Mount in the city, but all that remains are the retaining walls holding up the plaza they once sat atop.

That same site is holy to Muslims too. In the Islamic tradition, Muhammad made a miraculous journey from Mecca to Jerusalem on the back of a winged horse-like creature. From the Temple Mount complex, Muhammad ascended to heaven in a prophetic vision.

When Muslim armies conquered Jerusalem, the caliph built a domed shrine directly on top of the site, marking it as a Muslim site.

For the 2,000 years following the destruction of the Second Temple, Jewish access to the Temple Mount and even the walls surrounding it was subject to the whims of whoever was in charge.

Fast forward to 1928, and tensions between Jews and Arabs were sky-high. Until Husayni took power, tensions were mostly political, focused primarily on land, resources, and immigration. Husayni changed all that, bringing the Temple Mount complex to the front lines.

Under Husayni, the status and history of the holy sites became symbols of both sides’ nationalist aspirations. Whoever had the rightful claim to those temples had the rightful claim to the land.

Husayni launched a series of renovations directly on top of the Western Wall, where many Jews gathered to pray as it was the closest they could get to the most sacred part of the Temple Mount. This forced Jews to duck falling bricks while praying below. The Adhan, the Muslim call to prayer five times a day was also made louder. Young Arab men also threw stones at Jewish worshippers.

While some Jews were calling for Jewish control of the Wall, most were wary about upsetting the centuries-old status quo. Everyone felt strongly tied to their holy sites, but not everyone wanted to fight for them.

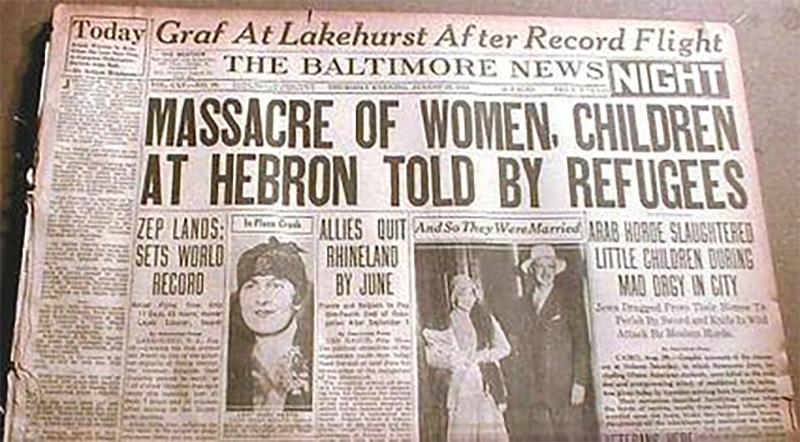

The Hebron Massacre

Within a year, Husayni’s moves had pushed tensions over the edge. In 1929, as Jews were preparing for the fast of Tisha B’av — commemorating the day the First and Second Temples were destroyed — many Jews held a procession in Tel Aviv and a rally in Jerusalem, shouting “The Wall is ours!”

Husayni had been preparing for this moment. He already had pamphlets ready, claiming the Jews were not only planning to take over the Wall, but had already “violated the honor of Islam.” He even added in false claims about “the enemy’s” rape and murder of innocent Muslims.

Other leaders helped spread his claims in mosques around the area, and a mob of angry young Muslims quickly rampaged through the Western Wall plaza. Young Jews formed volunteer security squads to protect the worshippers, but the violence quickly spread. Arab rioters vandalized shops, beat up pedestrians, and looted homes in Jerusalem and beyond.

Despite the violence, the Jews of Hebron weren’t concerned.

The Haganah, the defensive force set up by Jews to protect their communities from Arab attacks in the 1920s, tried to offer protection to Hebron’s Jews, but they declined the offer. There had already been smaller riots in other areas in 1920 and 1921, but they had never reached Hebron.

“The Jewish leaders in Hebron in 1929 were absolutely sure that other Jews would be hurt, but not us, because we live in peace with our Arab neighbors,” Yardena Schwartz, author of Ghosts of of a Holy War, explained.

That trust ended up being misplaced. The riots came to Hebron, turning into a full-fledged massacre.

“Women, teenage girls were raped in front of their families before they were killed. Parents were butchered by their neighbors in front of the eyes of their children,” Schwartz said. “Babies were slaughtered in their mother’s arms. Rabbis and yeshiva students were castrated. Some people were burned to death. Synagogues and homes were looted and destroyed. The Jewish community of Hebron, one of the world’s most ancient Jewish communities that had existed there for thousands of years, was decimated and evacuated by the British authorities who ruled Palestine at the time, and they were told never to return.”

The massacre didn’t just decimate the ancient Jewish community of Hebron; it destroyed any semblance of trust or hope of coexistence. Many of the Jews of Hebron changed their minds about Zionism, but as pious people, they shaped their Zionism within their religious views.

Less than 20 years after the Hebron massacre, Israel declared independence. The next day, five Arab armies invaded. After a year of war, the Jewish state emerged alive, but the Temple Mount and Hebron were both in the hands of Jordan. Jews were barred from their holy places, with Jordan even demanding baptism certificates from tourists who wanted to see the holy sites to ensure there were no Jews among them.

For nearly two decades, Hebron, like the rest of the West Bank, was empty of Jews and full of Arab refugees of the war. Then everything changed again with the Six-Day War.

Jews return to Hebron

In under a week, Israel wrested control of East Jerusalem and the West Bank from Jordan, as well as the Sinai and Gaza from Egypt and the Golan Heights from Syria. After 40 years, Hebron’s Jews began to return home.

“It was only natural that after we liberated the city that we would come back here first. There was just a tremendous pull back to our properties and also back to being close to the forefathers and mothers,” Fleisher said.

That proximity to history and sacred spaces attracts a certain kind of person. One who cares deeply about the past, one who puts themselves on the front lines to ensure antisemitic violence doesn’t repeat. Some might call them extremists, and some wear that badge proudly.

“Who makes it to the top units, the elite units in the army? People who are extreme,” Fleisher noted.

“And the people who live in Hebron are just like that. They are a certain kind of elite. They are extremely dedicated to Jewish history, to the Bible, to Jewish rights. And they recognize, they have a sense of the fight that has always existed, and they now have the hand, the ability to push back against our abusers. They have been schooled in Jewish history and in Jewish thought and have a keen sense of our rights. And yes, there are some tough folks around here. That’s what you gotta be in the Middle East.”

At first, the Israeli government didn’t intend to allow Jews back to Hebron. Initially placed restrictions on Jewish worshippers at the Tomb of the Patriarchs, wary of upsetting the local Arab population. Eventually, though, enough Jews had moved to Hebron that the government relaxed its restrictions.

No one was sure what would happen to the West Bank after the war. Some people favored returning it unilaterally, while others urged the government to hang on to strategic portions essential for security and national identity.

Even David Ben Gurion, an avowed secularist who had called for a return of most of the conquered lands, believed that Hebron should remain under Israeli control. That goes to show how important the city is – not just to the religious, but to the Israeli character and Jewish story as a whole.

That sacred character of the city made it a major flashpoint. Through the 1980s and 90s, life in Hebron was tense.

In 1993, Israeli and Palestinian leaders signed the Oslo Accords, meant to bring peace after decades of conflict. But that peace never materialized. Terrorism got even worse and settlements spread further throughout the West Bank. Many Israelis and Palestinians became disillusioned with the prospect of peace, but the deal was still signed on paper.

Tens of thousands of Israelis living in the West Bank were especially concerned: Would their government uproot them from their homes to make way for a Palestinian state? If it did, would they get peace and quiet – or more attacks?

In 1994, tensions boiled over once again with one of the most shocking attacks to hit Hebron. This time, it came from a Jew.

The Ibrahimi Mosque massacre

A small Jewish terrorist underground had targeted Arabs in the West Bank since the summer of 1980. The terrorists were outraged that the Israeli government had signed a peace deal with Egypt and had uprooted Jewish settlements in the Sinai Peninsula to make the agreement happen.

Baruch Goldstein, a Jewish resident of the Kiryat Arba settlement near Hebron, didn’t start out as part of this group. He did, however, have an apocalyptic vision of Jews as holy warriors, liberating themselves by the sword.

In his day-to-day life, Goldstein was a physician serving the Jews of Kiryat Arba. According to some reports, he refused medical care to non-Jews – an early warning of the radicalism poisoning his mind.

On February 25, 1994, that radicalism reached a bloody conclusion. Goldstein rose early that morning, immersed himself in a ritual bath, and then headed to the Tomb of the Patriarchs. That year, the Jewish holiday of Purim coincided with the Muslim holiday of Ramadan, and the mosque above the tomb was crowded with worshippers for the dawn prayer.

Goldstein carried an automatic rifle with him, shooting into the crowd of 800 Muslims praying at the mosque. Twenty-nine Palestinians were murdered, with the massacre only ending after Goldstein was beaten to death by the crowd.

Violence erupted throughout the West Bank as Palestinians expressed outrage at the massacre.

Despite the violence, the peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) continued. Three years later, the two signed an agreement that still shapes Hebron to this day.

The split of Hebron

Under the agreement, the PLO controls 80% of Hebron, an area now known as H1. The IDF controls the other 20% of the city, H2, which includes Jewish settlements, the Tomb of the Patriarchs, and houses tens of thousands of Palestinians.

Palestinians living in H2 have harsh restrictions on their basic freedoms, partially because of the violence that erupted after the 1994 massacre. The Israeli government and the Jewish community of Hebron say the restrictions are in response to the constant threat of terrorism, a threat that many residents of Hebron have experienced firsthand.

“My dad was killed in our home, in front of my mom,” Shlissel explained. “She said, ‘How can I stay here, in my house, after what I saw with my own eyes? What will I do now?’ Then she said, ‘On the other hand, if I leave Hebron, that will only motivate more terrorists to kill Jews.'”

Many Palestinians say that these security restrictions are merely an excuse for a land grab, a way to make the Arab community so miserable that they’ll just pack up and leave.

Abu Hassan, the director of Alternative Tours, insisted that it’s the Palestinians who need protection, not Jews.

“They [settlers] have arms, they have soldiers to protect them. Our people need protection. Not from the soldier, from the settlers, right?” said Abu Hassan. “I have a car. I have yellow (Israeli) plates. I cannot drive here because if they found out I’m a Palestinian, there would be a problem. I have an Israeli residence. I can’t come here with my car because I’m an Arab.”

Abu Hassan added that the 35,000 Arab residents in H2 can’t drive to the other side to shop or do errands. Instead, they have to carry everything by hand and go through the checkpoint between the two sides by 8 p.m. every night.

Hebron’s Palestinians paint a dire picture of harassment by Jews, of a strangled economy, of a constant choking sensation from all the restrictions on movement.

Oddly enough, the Jews of Hebron report a similar feeling.

Even though the army is there to protect them, they know that their presence in Hebron relies on a well-funded, heavily armed military force that cordons off certain areas for their almost exclusive use while keeping them out of the majority of Hebron. They’re well aware that without this military protection and without these restrictions on their neighbors, there would be no Jewish community in Hebron at all.

“The army understood that there’s a great tension here, and they basically made a sterile zone where the Jewish ghetto existed, which is now once again a kind of sterile Jewish ghetto, but that allows our community to live here unmolested and unharmed,” Fleisher said.

Clashing narratives

In Hebron, history saturates every step, every building, every interaction. There is no “past” here, no “was.” It feels as though Abraham has just handed over his 400 shekels. It’s as though the axes of 1929 are still cleaving bodies apart, the bullets of 1994 still firing into the crowd. It’s like stepping into the most concentrated form of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: fervent, bitter, and inescapable. Most Jews and Arabs seem unable to accept the other’s narrative.

Abu Hassan insisted that the Jews murdered in the Hebron massacre were Jews who arrived with “another ideology,” not the Jewish families who had been living there for centuries.

While he may believe that, the fact is that native-born, Arabic-speaking Jews were the first to be killed, and Hebron’s community wasn’t Zionist, at least not until the massacre.

The mob didn’t ask if someone was a Zionist before they cut them down, but that’s an inconvenient narrative for some. It’s much easier to believe that the massacre of 1929 happened for a reason beyond blind religious extremism.

On the other side, some Jews genuinely believed that Baruch Goldstein had prior knowledge of an upcoming massacre.

They claim that he was protecting the Jews of Hebron, even if he chose to do it in a way most Jews condemn. However, there is absolutely zero evidence for this belief. It’s a convenient story, not a true one. Some extremists treat Goldstein as a hero, even visiting his grave on pilgrimage.

People believe the stories that fit their narratives, that confirm that they are right, but the narratives that dominate this city are both riddled with inconsistencies and inconvenient half-truths.

Is there a way out of this cycle of violence that allows both people to live in dignity without fear, without anger, in the land of their ancestors?

Abu Hassan insists that both sides need to understand that Hebron is their joint home. “Either we live together, or we can die together.”

“Abraham had two sons, Isaac and Ishmael, which means Jews and Muslims are cousins. We are from the same place,” said Abu Hassan.

Fleisher agrees. “One of the ways that I get over the tensions between Arabs and Jews is I say, look, we have a joint father here. We have a shared father. We have something that we can actually agree on and share and love.”

The people of Hebron have grown up haunted, not just by the Biblical figures that make this place holy, but by the wails of their murdered families and friends. When you live in the shadow of your martyrs, you become pretty uncompromising – both in your vision of the past and your hopes for the future.

But maybe there’s another way, one that honors history while looking to the future.

It’s not a coincidence that the groundbreaking deal that normalized Israel’s relationship with some Gulf states is known as the “Abraham Accords.” The man who set the region on this collision course could also be the man to set it free.

We are all Abraham’s children. We are all equally valid, important, and beloved. And as long as we recognize that in one another, there is hope for Hebron — and for the entire region.

Originally Published Apr 15, 2025 05:08AM EDT