Long dismissed as their grandparents’ vacation lore — shuffleboard, supper clubs, and all — the Catskills’ legendary Jewish resort scene is getting a second life. But this time, it’s through TikToks, road trips, retro merch, and museum exhibits. For younger generations hungry for connection, culture, and a dash of camp, the Borscht Belt offers more than nostalgia. It’s a rediscovery of joy, community, and the wildly specific magic of Jewish summer in the mountains.

Decades after the last check-outs at Grossinger’s and the Concord, that world is being revisited by their grandkids. Gen Z and millennial Jews are diving into the Borscht Belt’s legacy — not out of nostalgia, but curiosity, pride, and a craving for something that feels both deeply Jewish and totally their own.

What was the Borscht Belt, and why did it die out?

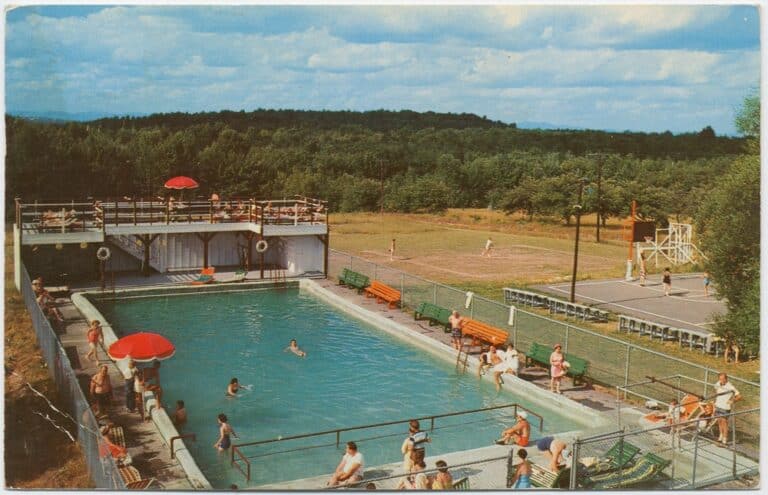

The Borscht Belt, a string of Jewish resorts scattered across New York’s Catskill Mountains, began as a response to exclusion. In the early 20th century, as Jewish travelers were routinely turned away from gentile-owned hotels, they built their own summer havens — modest bungalow colonies and sprawling all-inclusive resorts where Jewish families could relax, celebrate, and connect. But what started as a workaround became a cornerstone of American entertainment. Hotel stages in the Catskills launched the careers of some of the biggest names in entertainment, with featured performances by RuPaul, Barbra Streisand, Woody Allen, Sid Caesar, and Sammy Davis Jr.

According to Marisa Scheinfeld, the founder of the Borscht Belt Historical Markers Project, the Catskills weren’t just a Jewish story, but an American one.

“The Borscht Belt was created because Jews were excluded from vacationing elsewhere,” Scheinfeld said. “It was born out of antisemitism. But what happened there — the culture, the comedy, the community — was extraordinary.”

“This was where the all-inclusive hotel model started,” she continued. “There were wellness retreats in the 1920s. A vegetarian hotel with a solarium and yoga. Mel Brooks got his start there. So did Joan Rivers, Jerry Seinfeld, Rodney Dangerfield. It became a launchpad for popular culture.”

“The Borscht Belt was more than just a slice of Americana tucked away in the Catskills. When people talk about the golden age of American vacationing — the 1950s and ’60s — this region wasn’t just part of it. It set the model,” Isaac Jeffreys, a photographer and collaborator on the Borscht Belt Historical Marker Project, added.

For decades, the region thrived not just as a vacation spot but as a proving ground for Jewish performers and a vibrant center of communal life. The laughter, food, and cultural pride that filled those hotel dining rooms became a lasting part of American pop culture, all born from a place where Jews, once shut out, created a world entirely their own.

The Borscht Belt’s decline began in the late 1960s and accelerated through the 1970s and 1980s, as air travel became more accessible and younger generations opted for new kinds of vacations. Jewish families who once returned year after year moved to the suburbs, assimilated, and stopped seeing the Catskills as their only option.

Many of the once-thriving resorts were abandoned, demolished, or repurposed. But in recent years, there’s been a renewed fascination with the region — fueled by nostalgia, a growing appreciation for mid-century design, and a broader cultural reckoning with stories of immigration, exclusion, and resilience. Younger audiences are rediscovering the Catskills through Instagrammable boutique hotels, “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” retro aesthetics, and a deeper interest in the Jewish roots of American comedy and culture.

Bringing the Borscht Belt to Brooklyn

This renewed interest isn’t just about kitsch or curiosity, but about finding new ways to engage with heritage. For many young Jews, the Borscht Belt has become a lens through which to explore identity, memory, and belonging in a modern world.

“We recently participated in Seltzer Fest, which we see as part of the story of Jewish New York,” said Rebecca Guber, director of The Neighborhood. “It got us thinking about how to explore our own history and bring it into a contemporary context.”

Movies, Guber’s team determined, were a great way to connect with Jewish history. After the success of their “Yentl” event, the team began discussing other iconic Jewish films. “We realized that we all loved ‘Dirty Dancing,’” she said. Set in the Catskills, the film resonated not just for its cultural impact, but its love for New York summers and New York Jews. “So many of the people going up to the Catskills were living in Brooklyn and other parts of New York City,” she explained.

For Guber, the Borscht Belt is also personal: “I still go to a Jewish bungalow colony, one of the last remaining old school bungalow colonies.”

She said the whole staff visited last summer and felt like they had “flashed to a different era.” Once they landed on the “Dirty Dancing idea, “everyone we talked to was like, ‘Yes,’” and they began brainstorming how to give the event a modern twist — something that wasn’t just about nostalgia, but about celebrating both history and the contemporary Jewish experience.

That spirit of blending history with the present is at the heart of Catskills, BK: Dirtier Dancing, The Neighborhood’s upcoming rooftop event in Williamsburg. Taking place June 17 at the Moxy hotel, the evening channels the energy of the Catskills’ Borscht Belt — once a summer escape for Jewish New Yorkers — through a Brooklyn lens. There’ll be klezmer music from Michael Winograd and the Honorable Mentshn, DJ sets, drag, themed snacks from Israeli chef Eli Buliskeria, and nods to “Dirty Dancing” from the soundtrack to a photobooth.

But it’s more than just a retro party. The event reflects on the Catskills as a site of cultural memory — a place where Jewish families gathered, celebrated, and created community — while asking what that legacy might look like today, on a rooftop, in a very different New York.

Why young people are gravitating back to the Borscht Belt

The Neighborhood is far from the only group celebrating the Borscht Belt and its legacy. In recent years, the Catskills and other parts of 20th-century Jewish culture have been making a comeback. From a spike in interest in Yiddish and klezmer music to renewed interest in the Jewish deli, millennial and Gen Z Jews have returned to different elements of Ashkenazi culture that many of their parents and grandparents rejected.

“For me, it’s about community,” Guber said. “The Catskills really started as a way for Jews to leave the city and take a vacation at a time when they weren’t welcome anywhere else. It was a respite — not just from urban life, but also a place where Jews could feel comfortable together.”

She pointed out that it wasn’t about private retreats or peaceful isolation, but about returning to a communal Jewish space. Guber noted that the original bungalow colonies were modeled after dachas — the modest country houses common in the former Soviet Union and Ukraine. “The Catskills culture wasn’t going to your own big country house. It was about being together. It was about being kind of loudly Jewish.”

Guber herself still spends summers at Rosemarins, a rare surviving bungalow colony that hasn’t changed much since the 1960s.

“It was shrinking,” she said, “but during the pandemic, it came back — 100% full.” Families who didn’t want to be isolated upstate flocked there for a sense of closeness, even if that meant “living in a little shack 20 meters from another little shack.”

That return to the community wasn’t just temporary. “Now it’s not just older folks — it’s young families, people in their 20s and 30s,” she said. “It’s become this real intergenerational thing again, and I think that’s part of what made the Catskills so special in the first place.”

Guber sees the renewed interest in the Catskills — and Jewish cultural history more broadly — as part of a generational shift.

“Our parents’ generation had more of an assimilationist mindset,” she said. “But younger folks don’t really feel that. Their Jewish identity, history, and heritage are things they want to explore and investigate. It’s not the only piece of who they are, so it feels okay to dig into it.”

Andrew Jacobs, founder of the Borscht Belt Museum, sees the renewed interest in the Catskills as part of a broader cultural yearning.

“It’s not an easy time to be a young American,” he said. “I grew up in the ’70s and ’80s, and my worldview is very different from younger generations today. These are hard times, and I think there’s a natural tendency to look back, to search for a version of America that felt more connected, more hopeful.”

For Jacobs, one of the most powerful elements of the Catskills story is the deep sense of community. “There was this real togetherness,” he said. “People spent whole summers side by side — sharing kitchens, sharing bungalows, seeing each other every day. The social fabric was just richer.

“Maybe people are yearning for that — a time when life was a little slower, and being together meant more.”

Honoring the history of the Borscht Belt

Scheinfeld, the photographer and author behind “The Borscht Belt: Revisiting the Remains of America’s Jewish Vacationland,” grew up steeped in the history of the region, even as it was unraveling.

“In many ways, my book was an elegy to the Borscht Belt,” she said. “I grew up there. My parents brought me up from Brooklyn when I was five. My grandparents had vacationed there. My great-grandparents too. There was always this sense of something bigger that had once existed — an amazing network of hotels and culture.”

As a teenager in the 1990s, Scheinfeld worked as a lifeguard at the iconic Concord Hotel, once one of the largest resorts in the region. “By then, you could really see the decline,” she said. “There had been over 500 hotels, 1,000 rooming and boarding houses, 50,000 bungalows. And suddenly, it was just ruins. What was left behind became a symbol of failure and economic collapse.”

When her book was published in 2016, Scheinfeld said it helped reopen a long-closed chapter. “The Borscht Belt mostly lived in memory by then. People didn’t want to confront the ruins,” she said. “But I felt it was important to look, not just at what was lost, but at what was built, what it meant.”

As she began giving talks around the country — more than 300 in total — her personal story and the visual record she’d created helped bring new attention to a fading chapter of Jewish American life.

This led her to Jerry Klinger, the founder of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. Klinger, who previously commissioned historical marker projects in places of Jewish significance like Cochin, India, proposed the idea of bringing markers to the Borscht Belt.

Scheinfeld’s pregnancy and COVID-19 put a pause on the project, but a few years later, once the world reopened, the urgency of the project resurfaced.

“Half the sites in my book were already gone. The other half were burning,” she said. “Hotels have caught fire. Others have been repurposed into meditation centers, Orthodox vacation spots, rehab facilities, even a prison. These places were disappearing — and there wasn’t a single marker saying, ‘This happened here.’”

The Borscht Belt Historical Markers Project is slated for 20 markers spanning Sullivan and Ulster counties. So far, 11 have been installed. Four more will be dedicated this summer.

“We didn’t just want to put them on the side of the road,” Scheinfeld said. “We wanted people to actually see them: in libraries, town centers, courthouses. Places where people are already going.”

These aren’t your average plaques. Each marker is double-sided, full-color, and features photos and QR codes that bring the history to life. “The idea is that people can stumble on them and suddenly learn something about this place — that a hotel used to be there, or that Joan Rivers once performed in that town.”

At a recent dedication in Ellenville, for example, the marker highlighted the area’s contributions to Jewish comedy. “We mentioned hotels like the Nevele and the Fallsview,” Scheinfeld said, “but we also honored the comedians and had Gilbert Gottfried’s wife speak, and Buddy Hackett’s daughter. That’s what we’re trying to do: celebrate and educate.”

And as the historical markers project blooms, the Catskills continue to evolve, with new Airbnbs, breweries, and boutique hotels popping up. Scheinfeld hopes the markers provide some grounding. “There’s all this cool, new stuff happening,” she said. “And then there’s the marker trail, sitting beside it. It’s a reminder of what came before.”

Jeffreys traces his Catskills interest back to teenage explorations of abandoned buildings. “I’ve been a photographer since I was about 14,” he said. “Even early on, I was really fascinated by these spaces that felt like worlds left behind.”

He sees his role as helping to visually recapture the spirit of the Borscht Belt at its peak: “I’m trying to characterize the Borscht Belt in a way that feels true to how it actually was: lively, colorful, bold,” he said. “A picture really does speak a thousand words. You pass by a little black-and-white photo on a tiny plaque and maybe don’t think much of it. But these markers, they’re big, they’re colorful, and they’re designed to stop people in their tracks.”

For Jeffreys, that layered legacy — the mix of sound, architecture, and community — deserves far more recognition than it’s gotten. “There were 538 hotels,” he said. “That’s not a footnote. That’s a movement. And yet, we’ve seen so little preserved. Most of it was demolished without much thought to the history. There’s been no real, concrete effort to save it.”

As the physical landscape of the Catskills transforms, so too does the emotional connection people have to it. While historical markers offer a literal way to trace the past, for many, the real journey is personal. Podcasts, social media accounts, and grassroots projects are helping a new generation reconnect with the region, not just as a vacation spot, but as a site of memory, identity, and inherited joy. That was the case for Jennifer Stewart, whose deep dive into Borscht Belt history began while bored during the pandemic.

“It started as a passion project during the pandemic,” Stewart, host of “The Borscht Belt Tattler” podcast, said. Stewart had visited the Catskills with her parents growing up, but it wasn’t until she began working on the podcast that she uncovered just how deeply her family was connected to the region, tracing ties back to her grandmother. Like many Borscht Belt stories, she found that it all came back to family.

“During that isolated time, reminiscing about those memories really lifted my dad’s spirits, and I found myself wanting to learn more, why this place made people so happy. I just fell down the rabbit hole,” she said.

“I hadn’t seen anyone really documenting these stories,” she continued. “My father passed away recently, and it made me realize how quickly we’re losing this generation. I know it sounds a little morbid, but if we don’t capture these memories now, they’re gone forever. That gave me a real sense of urgency.”

With over 40,000 podcast downloads, Stewart is proud of what she’s built. “People love hearing these stories. I know I do — I could listen for hours. I just had to find out if others felt the same. And they did.”

Innovating for the next generation

Jacobs first got to know the region as a child and now owns a home there, but his deeper connection began when he directed “Four Seasons Lodge,” a documentary about a group of Holocaust survivors who spent summers together at a small bungalow colony in Ellenville. Not long after, he was invited to join the nonprofit behind the Catskills Borscht Belt Museum, formalizing his involvement in preserving the area’s history.

Jacobs said his interest in the Borscht Belt deepened while reporting a story for The New York Times about summer life in the Catskills in 2006 and 2007.

“I realized there was this whole world up there that wasn’t really getting attention,” he said. At the time, many bungalow colonies were still active, and a growing number of Hasidic families had moved in, giving the area a sense of continued, if transformed, vibrancy.

As he explored further, Jacobs discovered layers of history he had only been vaguely aware of — a cultural and historical richness that surprised him. “It felt underappreciated and underrecognized,” he said. “But I also started to see that the stories from this place — of community, resilience, exclusion, and creativity — really resonate today. There’s a lot we could learn from them.”

Jacobs explained that before the Catskills Borscht Belt Museum found its current momentum, the project had been in the works for nearly two decades with little visible progress. When he joined the board in 2022, the team made a strategic pivot to scale back and buy an existing building instead of building something new.

“It was faster, way less expensive, and we wanted a space that already had a historical connection to the Borscht Belt era,” he said.

The appeal isn’t just to people who lived through the Borscht Belt era, though Scheinfeld says those visitors are always welcome at their dedications. “No shade to the Boomers,” she said with a laugh. “But this project isn’t just for them. It’s for my generation, my son’s generation. For millennials and Gen Z and whoever’s coming next, people who didn’t grow up knowing this history.”

For her, the markers are a way of preserving the past while speaking to the future. “They’ll be here long after I’m gone,” she said. “That’s the point — to create something lasting, something that will help people remember, and maybe even discover it for the first time.”

That sense of legacy—honoring the past while inviting new eyes to see it—runs through many of the Borscht Belt revival efforts. While the markers offer a permanent reminder, others are finding more playful ways to spark curiosity. To bridge the generational gap, the museum has leaned into one of the region’s most iconic exports: comedy.

“That’s really how we reach new audiences,” Jacobs said. “We host comedy shows with contemporary talent — younger, up-and-coming comics — and that’s where we’re seeing real engagement from younger folks.”

For Jacobs, humor is the throughline that makes the museum’s work feel both rooted and expansive. “Comedy is universal,” he said. “It gives us a way to celebrate the past while keeping it alive and relevant in the present.”

The comedy shows are just one of the many initiatives the Borscht Belt Museum has tackled, including Borscht Belt Fest and the Borscht Belt Film Festival. Jacobs admitted that launching so many programs simultaneously may not have been the most rational plan, but he has no regrets.

@marcymccreary Growing up, I spent my summers at a Catskills resort hotel in an area affectionately referred to as the “Borscht Belt.” This museum in Ellenville, NY captures the nostalgia of the area and the era #borschtbelt #catskills #nostalgia

♬ Dirty Dancing: (I’ve Had) The Time Of My Life – Dynamite

Jacobs admitted that launching a museum, a film series, a comedy program, and a festival all at once may not have been the most rational plan, but it felt like the right moment. “We never intended to do all of this,” he said. “The festival and the comedy shows just sort of popped onto our radar, and we thought, this is a no-brainer. Even though no sane person would try to start a museum and a festival and a comedy series at the same time, we just went for it.”

This year’s Borscht Belt Fest in July boasts dozens of food vendors, 25 comedians, live music, panels, a rugelach bake-off, and an oral history initiative.

That oral history project, in collaboration with Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, will be one of the centerpiece efforts. Funded by a federal grant tied to the 250th anniversary of the United States, the team plans to record personal stories throughout the weekend at three different sites. “We’re doing a whole blitz of oral histories,” Jacobs said. “It’s going to be amazing.”

Embracing the diversity of the Borscht Belt

While the Borscht Belt is most closely associated with Jewish life, its legacy of creating space for the excluded inspired parallel movements. In the mid-20th century, Black vacationers established their own Catskills havens, like the historic Peg Leg Bates Country Club, founded by the famed tap dancer and one of the few resorts in the region to cater specifically to Black guests during segregation. Similarly, LGBTQ visitors carved out their own spaces in the area — including Casa Susanna, a bungalow colony for transgender women and cross-dressing men in the 1960s — with certain resorts and bungalow colonies quietly becoming queer-friendly long before it was mainstream.

These parallel communities echoed the original spirit of the Borscht Belt: creating joyful, affirming spaces where people who were shut out elsewhere could finally feel at home. For those working to honor the Catskills’ legacy, highlighting the region’s diversity is key.

At The Neighborhood’s Catskills, BK, the event intentionally reflects a broader, more inclusive vision of Jewish life — one that stretches beyond nostalgia. “We brought in DJ Joco, who’s Mizrahi, because we want to include different Jewish stories and musical traditions,” Guber said. “And both of our DJs come from the queer community. For us, being explicit about inclusion — especially in Brooklyn in 2025 — is key.”

That sense of collective belonging extended beyond the Jewish community. As the Neighborhood team dug into the history, they found that other marginalized groups had also made space for themselves there. “It became a place for outsiders,” Guber said. “And I think that still resonates — the idea of having somewhere to just be Jewish, or just be yourself.”

By foregrounding different identities and perspectives, Guber hopes to recreate the welcoming spirit that defined those spaces.

“When people who’ve felt like outsiders feel seen, it makes everyone feel more welcome,” she said. “It’s like — you might be Ashkenazi and your grandparents went to the bungalows, and you already feel like you belong. But you’ll feel even more at home if everyone else does too. That’s a win for everybody.”

Scheinfeld sees the region as a place of layered histories and communities — not just Jewish, but many others, too. It became a refuge for artists, Black people, Hispanic people, queer people — those outcasted from society — who created their open space.

Her next book, in fact, is exploring those lesser-known histories. “A lot of these other communities followed the Jewish model — if you don’t want us in your club, we’ll make our own,” she said. “The Green Book, which helped Black travelers find safe places to stay, was directly inspired by the Jewish Guide, which in 1917 literally said on the cover: ‘Places Where Jews Are Welcome.’”

That spirit of resilience and reinvention isn’t just a story of the past — it’s a framework for understanding the present. The Catskills may have been built by and for Jews, but the ethos behind the Borscht Belt — creating community in the face of exclusion — resonates far beyond. It’s a thread that Scheinfeld and others are now pulling on to uncover parallel histories, spark dialogue, and make the legacy of the Borscht Belt feel inclusive and alive for a new generation.

One of the Borscht Belt Museum’s central challenges, Jacobs said, is finding ways to make the history of the Borscht Belt feel relevant to younger audiences, not just those who remember it firsthand: “We do have a built-in audience of what we call the ‘resort nostalgics’ — people in their 50s and up who lived it. But we can’t take for granted that younger people will automatically connect to it.”

For Jacobs and the museum team, nostalgia is a powerful entry point — especially in a cultural moment when people look back for inspiration and meaning. “There’s always a nostalgic angle,” he said. “Even when you’re telling tough stories about exclusion, antisemitism, and why the Borscht Belt had to exist in the first place, you can still tap into a warm, emotional thread.”

Jacobs also emphasized the importance of highlighting the role immigrants played in shaping American culture, especially in the Catskills. “When we talk about comedy and entertainment, we’re really talking about something that was built by immigrants,” he said. “Mainstream American culture — especially stand-up comedy — is deeply Jewish. And a lot of people don’t know that.” He sees drawing those connections as not just educational, but essential. “It’s a powerful way to counter this impulse to ‘other’ people — to marginalize them. When we show how foundational these contributions are, it changes the narrative. It brings people in.”

But while the museum focuses on illuminating the past and reshaping mainstream narratives, others are quick to note that much of the Catskills’ present-day story remains hidden in plain sight. The legacy of immigrant-built culture may run deep, but so do the thriving, if often overlooked, communities that still return to the region every summer.

Jeffreys pointed out that a huge part of Catskills life still flies under the radar. “You’ve got these Instagrammable hotels side-by-side with hundreds of bungalow colonies and summer camps — many of them now Hasidic-owned. It’s estimated that over 100,000 people come up here each summer just for that,” he said. “So you have these completely alive, vibrant summer communities — but because they’re not part of the ‘mainstream’ narrative, they get overlooked.”

That, to him, is the frustrating disconnect. “People say the Borscht Belt is dead. But it’s not dead — it’s just different. The cultural moment of the 1940s and ’50s might be gone, sure, but the core idea — escaping the city, building a summer community — is still here. It’s just happening in different ways.”

Originally Published Jun 15, 2025 12:13PM EDT