Schwab: From Unpacked, this is Jewish History Nerds, the podcast where we nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner.

Schwab: And I’m Jonathan Schwab. And this week, Yael, you’re teaching me something. I usually know at least what the topic or title is. I literally have no clue. I forgot to even look at what the name of the episode was that we’re recording. So I know nothing.

I actually think it’s something you’re gonna find really intriguing because it melts together a whole host of Jewish cultural ideas in a form that we don’t often associate with rabbinic Judaism, and that is the form of magic. So we’re going to be talking a little bit about Jewish magic, about Jewish approaches to demons, and particularly we’re going to center this discussion around the Babylonian incantation bowls. Are those objects that you have ever heard of?

Schwab: I like it already.

Ooh.

You know, you had me at magic and demons and then lost me at Babylonian incantation bowls.

Yael: So I often saw them referred to in more amateur sources as devil magic bowls, even though they’re really demon magic bowls. But I did see some references to devil magic bowls. And the only reason I bring it up is that when you Google devil magic bowls

Schwab: Mm-hmm. This is a crucial distinction, yeah.

Yael: The results that you get refer to the Kansas City Chiefs and how they have employed devil magic to win most of their games in the past season.

Schwab:I know. Yes, I am familiar with like devil magic.

Yes, as a as like a sports term, right? When a team just inexplicably does really well.

Yael: Yes. So there were a lot of references to the Super Bowl being a devil magic bowl. That was not something I was expecting. But what we’re going to.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. nice. because of the ball. So like the Super Bowl, does this also not have anything to do with the thing I eat cereal out of?

Yael: It has almost nothing to do with the bowl you eat cereal out of except that the vast, vast majority of the bowls that we are going to talk about are the size of cereal bowls. And most scholars refer to them as being the size of cereal bowls with the exception of a very few in number which are described as being the size of salad bowls.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.I’m getting that feeling. I don’t know if you’ve ever had it, but the more you say something, the more I realize how strange of a word bowl is.

Yael: Yeah, it’s a little weird, but you know, I agree with you. think every word is weird when you repeat it multiple times. So what’s that from? That’s a made up word. All words are made up.

Schwab: Yeah. All words are made up. That is from an Avengers movie.

Yael: That’s like a Drac. That’s what Drac says. could call. very, very nice. Deep, deep, deep cut. Deep cut. OK, so I’m going to step back and give you a little bit of history about these bowls. Just so you know, there are approximately 3,000 of them that have been found. The ones that have been found in archaeological digs were found in what is modern day Iraq, which was then Babylonia, hence Babylonian incantation bowls. But many of the bowls were not actually found in situ which is found, you know, where they actually were.

Schwab: Sure.

Mm-hmm.

Yael: A lot of them that we know about have been found in the collections of individuals because they may have been found over the course of time and people took them home or brought them to museums. And because of that, we don’t actually know the provenance of those bowls. We can only assume that they’re related to the ones that have been found in Iraq.

Schwab: Hmm.So that already tells us, I’m guessing, that they were considered important or valuable enough that, like, we’re getting them from collections that were already established.

Yael: Yes, and they’re unique and we ascribe a lot of importance to them because, they are the oldest epigraphic material that we have about Babylonian or Rabbinic Judaism other than the Dead Sea Scrolls.

And we don’t know if that’s because they’re important and that’s why there were so many of them, or if just the fact that they were done on earthenware clay.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: led to them being preserved for a long time. Whereas something much more important might have been recorded on perishable material and we just don’t know about it because we have no access to it now.

Schwab: Hmm. Epigraphic? Can you for our listeners who are studying for the SATs or the GREs honestly, what does epigraphic mean? Okay.

Yael: So it’s basically written material, but I think very specifically it’s etched or engraved or in this case, ceramic. But I think you can use it in relation to other written materials.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Okay, good to know.

Yael: Let’s talk about when these bowls were first discovered by modern man and what we know about them and the modern scholarship that’s been done about these bowls. So in 1888, a professor of Hebrew at the University of Pennsylvania got permission from the Ottoman Sultan, as the Ottomans were at that time ruling Iraq, to do an excavation in Nippur. And Nippur in Iraq is where the vast majority of these bowls have been found, and particularly the vast majority of Jewish bowls. Because not all the bowls that we know about, the approximately 3,000 that we know about, are Jewish. The ones that we consider to be Jewish are the ones that are written in Aramaic, the language of the Talmud. There are also symbols written in Mandaic, which is an Aramaic dialect spoken or written by the Mandaian people who still exist today.

Schwab:Hmm. For this episode, I need to make like a word list of all the new terms.

Yael: My God, there’s so, it’s so, there’s so much going on here.So they’re monotheistic group that actually still exists today, highly insular, living in Iraq, living in Babylonia at the time. And they also used these bowls. And there are also some bowls written in Syriac, which was the language that was used by the Christians of the area at the time. And there’s a really, really tiny number in Arabic. Arabic had not yet taken hold.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. In Iraq. In the Nippur area, yeah.

Yael: As the major language, I’m realizing now I didn’t tell you when.

Schwab: Yeah, I was gonna say, because Arabic hasn’t taken hold, but there are Christians, I feel like I should be able to tell what time this is, but when are they originally from?

Yael: So we’re talking mostly about the 5th and 6th century AD. It’s possible that they were used from the 4th century through the 8th century, but the vast majority of them that have been timed have been timed to the 5th and 6th century. Towards the end, we see some Arabic bowls, and that’s around the time of the Muslim conquests, and that makes sense.

But we also know that Muslims have a very different approach to magic than Christians and Jews, or we know now. So it’s possible that the Muslim conquest is the reason why these bowls may have gone out of fashion. So let me explain, which I don’t think I’ve done yet, what makes these bowls magical, or what ties them to magic. Because as you mentioned, We have cereal bowls, we have salad bowls, there’s nothing particularly magical about them.

Schwab: You’re not using the right ones, but go on.

Yael: These bowls were amulets. They were used by people in Babylonia, both Jews and non-Jews, to ward off demons from their homes, as well as, in certain cases, to ask for things, though what one scholar calls prophylactic use of these bowls.

Mm-hmm.

Yael: If you thought that you had a demon in your home or you thought that you had some problem or you were having trouble conceiving, certain things were often addressed by these bowls. You would go to what we assume was a scribe because the text that was written on these earthenware bowls, particularly the Aramaic bowls, is highly similar to the text of the Talmud, for example. And we haven’t yet in the fifth or sixth century discovered copies of the Talmud written down. That will come later. So a…

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yeah. Meaning it’s a similar, like grammar, okay. Yeah. Yeah. Mm-hmm.

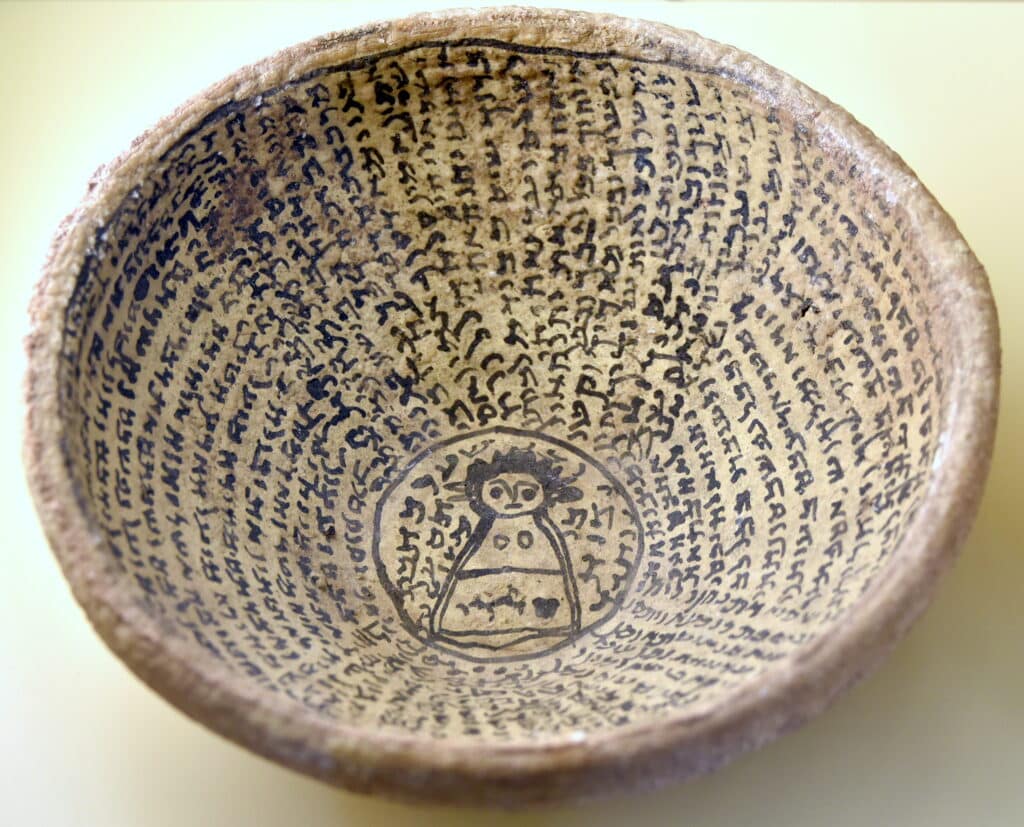

Yael: Font, font, and also grammar and vocabulary. And we’ll get to some of the traditional texts that were integrated into the bowls. But we assume that scribes wrote them because of the way in which certain Hebrew letters or Aramaic block letters were used on these particular bowls. And I should note, this is a highly visual idea. We will have photos of the bowls on our website and in the show notes that you can access. I actually had the opportunity to see some of these bowls in person a few months ago at the National Library of Israel where a few of them are housed. I didn’t at the time realize what their importance would be to me and hopefully to all of you after this, but it is interesting to see them up close. And I also was able to watch a few videos of lectures where scholars interacted with the material directly. And I even watched one video of a professor at Kenyon College making brand new incantation bowls out of clay with his students.

Schwab: Cool, that actually leads me to the question I had, which is that it sounds like you’re getting this custom made, right? There’s some sort of issue in your family. You’re going to somebody and yet you’re not going to a bowl shop and buying it off the shelf. Like this is.

Yael: Yes. That’s a great question. These were commissioned. And the way that the scholars discuss them is as having been commissioned by clients. There is a distinction between amulets that were written on these clay bowls and other metal amulets that we have from around that time. And one of the main differences is that the amulets on clay often invoke legal and biblical language. The metal amulets do not. And one scholar, Professor Manekin-Bamberger, posits that the reason for this is that the people who wrote the bowl amulets were scribes because they were familiar with legal language and with Jewish language and with biblical language.

Schwab: Sounds like you’re saying the bowl itself was not that hard to make. The writing, you had to really know what you were doing. Yeah. This professor at Kenyon College made a bowl. How hard could it be?

Yael: Right. Exactly. I made a bowl in ceramics in Camp Lavi in 1997, okay?

Schwab: And what incantations did you put on it?

Yael: I think it was Dalmatian print. I think we had really cool Dalmatian print glazed and I was really into it. So these bowls, the ones that were found in Nippur at least, the vast majority of them were found either inside or at the perimeter of homes. A lot of the homes had one bowl buried upside down at each corner of the house. And some had bowls under the lintel at the entrance to the house. so the lintel is like the bottom door post. Actually, I think it’s also the top door post. It’s the door post.

Schwab: Add it to the word Lintel.

Schwab: OK, it’s not a bowl you eat out of. So it’s the bowl you put your keys in that’s at the front of your house. But it’s not that either.

Yael: No, it’s not on display. They’re actually buried.

Schwab: Buried, because you don’t want people to know that you have whatever problem it is that you’re addressing with this incantation. Okay.

Yael: Well, it’s interesting that you say that. You’re right. People don’t want others to know. If others do know, they want to blame it on somebody else. Which is why a lot of the language in these bowls is to blame the demon. If trouble has befallen me, it’s because there’s a demon in my home, not because I did anything wrong.

Schwab: Like, when there is I don’t know some sort of tragedy in a family like multiple deaths or sicknesses or something that sometimes the advice you will get is to like, check your mezuzahs, you know, and then like I’ve heard a story like, and then they found that one of them had these errors in it, or was like, this was spelled wrong. like, I, it’s not my cup of tea. Um, but like, it sounds very similar to this sort of thing. We’re like, yeah.

Yael: Glad that you brought that up, because the connection to mezuzot is a clear one and mezuzot are a mainstream used amulet in most Jewish homes.

Schwab: That also, as we’re saying, connects, like, is in the doorpost, right? Like we were saying lintel before, yeah.

Yael: It’s in the doorpost

and it has text in the case of modern mezuzot, it’s biblical text, it’s the Shema. And actually one of the bowls that has been found does have language from the Shema written on it. So another connection there. But the use of mezuzot goes to show you that Judaism is not opposed to the use of amulets.

Schwab: Hmm.

Yael: But where do we draw the line between acceptable amulet and magic or witchcraft? Because the Talmud, which was being written contemporaneous to the time of the use of these bowls, decries witchcraft. But it’s okay with amulets and it acknowledges demons.

That being said, the way that we were entrapping these demons, which I’ll get to with respect to the burying of the bowls, was with words, sometimes biblical words, and sometimes magic spells. Magic spells that came from, some came from something called Hei-chalot (Hekhalot) literature, which were basically these magic handbooks that were in wide use in Judaism in late antiquity and early medieval times, some of which have been found in the Cairo Geniza.

Schwab: We’re gonna do, I think we’re gonna do a thing this season where we try to reference every previous episode, like Easter egg of like a previous episode.

Yael: My God, thank you so much for reminding me because I wanted to say one thing before when I was talking about the Mandaeans. A tenet of Mandaic belief is belief in the immortality of the soul.

Schwab: The immortality of the soul. That’s a Sarra Copia Sullam thing? Yes.

Yael: That’s Sarra Copia Sullam and Mendelssohn, who wrote essays and was in an essay contest where he beat Immanuel Kant and he wrote an essay on the immortality of the soul. I…

Schwab: Yes. Yeah. Yeah. Okay. Nice. See, all we’ve now as we’ve come into our fourth season, it all connects. And we’re talking about magic. We did a great episode on Hillel Baal Shem. And a lot of this sounds so similar to that, although it’s separated by a thousand years.

Yael: Yeah, but I did want to point that out when I saw the immortality of the soul. I was reminded of that. Cairo Geniza. We’re also gonna get to your bestie, Babatha, soon enough. So, where was I? we’re trapping the demons.

Schwab: Nice. Okay, great. We’re trapping the demons. That’s why the bowls are buried upside down, I assume.

Yael: So yes, very good. I forgot you have this like engineering physics background.

Schwab: If I was thinking about how to trap a demon, I would think about inscribing a bowl and then, you know, burying that bowl upside down because the demon is inside of it, obviously.

Yael: Right, so you have these four bowls buried at the four corners of your home. And on the inside of the bowl, you have an inscription and the inscription is spiral. It starts at the center of the bowl and it goes around in a spiral. And the word, doesn’t start from the outside rim. It starts from the center and goes outward

Schwab: Is there a significance to that? was wondering that like what starting from the outside in or inside out.

Yael: Yes, because you want to draw the demon all the way in to the center. And at the center of some of the bowls, and I’ve recently discovered that these are the more expensive bowls. If you’re looking to buy a bowl at auction anytime soon, the more expensive ones have an image of a demon at the center. The demons, to me, are you familiar with the artist Basquiat at all?they look to me like the people in Basquiat paintings. And they kind of have hair. They’re like stick figures with hair all over the place with very abstract body parts, a little Picasso-esque and importantly, with respect to these bowls, most of the demons are women, because obviously it’s all women’s faults. And they’re also naked. some of them are naked and they’re chained, because what we want is for our demon to be entrapped in these bowls. So there are three main types of inscriptions on these bowls.

Schwab: Backing up for one second, do we know this all just from like unearthing these bowls, but we don’t have like a instruction manual of how to write the bowls or anything like that?

Yael: That’s a great question. We don’t have an instruction manual on how to write the bowls.

Schwab: So we’re reverse engineering the entire process.

Yael: Correct. And that’s kind of why I thought of Babatha, because we are using these bowls to create a cultural history, to learn about how people lived at the time that they were written and employed. And it’s all conjecture. We are learning about the culture from these material artifacts. And what we’ve come out with makes a lot of sense and is very interesting, but the Talmud itself never mentions the bowls, mentions amulets, and it mentions demons, but not the bowls themselves.

Schwab: But this gives us like this, yeah, like a totally different insight into like, here’s how some people were living. Here’s something that people were practicing, even though it’s not mentioned in any way.

Yael: Okay, let’s take a quick break.

Yael: So when these bowls were initially discovered, it was generally thought that these were used by non-Rabbinic Jews, that this seemed to be something separate and apart from what we would call, let’s say, Halachic Judaism. As the scholarship has advanced, we no longer believe this to be true. There are enough bowls out there with inscriptions from the Bible, we have one with a verse from Isaiah. We have several with text from the Mishnayot, which is the base text for the Talmud. We have one that includes what we currently believe to be liturgical language, very similar to the Asher Yatzar blessing that people say for their continued health.

Schwab: So this whole practice isn’t mentioned in any rabbinic sources, but an awful lot of rabbinic material is like found its way onto these bowls.

Yael: And not only that, the clients who were commissioning these bowls have their names written on the bowls themselves. there are people with the title Rav or rabbi who are named as clients. Some of the bowls invoke Rav Joshua ben Perachiah. Some of them invoke Rav Hanina ben Dosa, who is a very well-known rabbi from that time. So we no longer believe that the use of these bowls was exclusive to non-Rabbinic Jews or more mystical Jews or the crunchy granola people on the outskirts of the town.

So there are a few different templates, let’s say, for particularly the Jewish bowls. Some of them begin with what is called his.

Schwab: I love how much you have really gotten into it. Like you said, we don’t have an instruction manual, but it seems like you have, I don’t know, really gotten all the information or most of the information that we know about what these bowls looked like and how they were made. Thank you for painting a very vivid picture of just the direction of the text, I feel like I am getting a real sense, you know, from picturing a cereal bowl at the beginning to like now imagining exactly what we’re talking about. With the very funny little demon, you know, caricature in the middle, yeah.

Yael: Yeah, I don’t know if you did this as a kid, but sometimes I would send away for prizes from the cereal box and I like I had a really cool cereal bowl from Kellogg’s that had all the different mascots of all the different cereals on it. Like that to me was my important bowl. That was the one that was keeping me safe in some way. don’t know what it was keeping me safe from, but you know I did ascribe magical powers to this Kellogg’s melamine bowl.

Schwab: Mm-hmm, to your favorite bowl, yeah, that makes sense. In which we’re trapped all of the Kellogg’s demons, I’m hearing.

Yael: Yeah, Tony the Tiger and, you know, Toucan Sam were never getting out of there. good point.

Schwab: And snap, crackle, and pop. There is something a little demonic as we think about them. They’re all, I don’t know, somewhat uncanny. Yeah.

Yael: It’s a little weird. It’s a little weird. I did want to mention, There have been 600 bowls, quote unquote, published. And so when we say a bowl has been published, we mean that a scholar has undertaken to study it, to study the words, to study the images, to study the provenance, and give us a sense of what this bowl may have been or who it was directed at.

Schwab: And you said though, if I’m remembering correctly from before, that we have 3000, we found 3000. Are they intact, these balls?

Yael: Close to 3,000, yes. Some of them are. I never having held one in my hands–

Schwab: Well, obviously you shouldn’t hold one in your hands because that’s how the demon gets out. But apologies to all of our listeners who take demons very seriously, but I am very cynical on the topic of demons.

Yael: Right, sorry. It is funny, there was someone in my Talmud class in 12th grade, a very, very nice guy who’s actually now a rabbi, who used to talk about demons in the Talmud all the time. And I thought about him a lot while preparing this episode because I remember being so weirded out by it at the time, not by him, he’s a great person, but I didn’t realize how significant demons were to Jewish life in late antiquity. And what’s interesting is we think that they’re significant because we have found these bowls and they were in many of the houses that were uncovered in these archaeological digs. And we’re surmising that they were important based on the fact that they survived and they still exist. And that’s because they are on earthenware clay. We have no idea if, you know, so let’s say there were four bowls in a home. There could have been 44 of something else that has completely disintegrated, and we don’t know. Exactly. I tried to think about it in a modern context where this is very niche.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yeah. Like paper writings that people hung up on their, know, yeah. Interesting.

A more general example I got from our producer, Rivky, which was helpful, was Beanie Babies. That, you know, Beanie Babies as religious icons, if scholars in the future were to find them and find that in my home I had six different Beanie Babies.

Schwab: Yeah.Hmm.

Yael: And in your home, you had 12 different beanie babies, and maybe some of them overlapped and some of them didn’t. Maybe one was an amulet for fertility and one was an amulet for success and one was an amulet for finding a spouse. You know, we obviously know that that’s not why we have ridiculous beanie baby boom in the mid 90s, but a future scholar might not know that.

Schwab: Yeah. Yeah.

Yael: Going back now with respect to some of the texts, just to give you a sense of how much text there was on these bowls, some of them would begin with an appeal to God, say, you know, like, let the gates of healing open for Jonathan Schwab, the son of Mr. Schwab in Queens, and then employ either a biblical excerpt or a known spell that we now have seen in later books of spells.

Some of the spells that are used on the bowls are identical to spells that were found in writing in the Cairo Geniza from a later date. So we see that the spells endured in some way. Correct. Like abracadabra continued to be used or what is it?

Schwab: Hmm. So the spells are like in continuous usage in some way, yeah.

Mm-hmm.

We’ve mentioned that before, right? That like Abra Kadabra also has some sort of Jewish origin to it. Yeah.

Yael: Yes, Abra, kids Abra, something is created. Abra is creation and Kadabra is as it is spoken. And I thought about that a lot with these bowls that, you know, the bowls mean something to us because they are a combination of material and words. And it is the words, presumably, that do the work of entrapping the demons. But we still need the material of the upside down bowl itself, to actually do the trapping.

Schwab: Yeah, we haven’t done an episode on, on the golem, right? Like the, legend of the golem. But it reminds me of that a little bit also of like, in that legend, ou have to make this giant man like out of a material, but what animates it is the word. Like there have to be specific Hebrew words of power that like, you know, can, can bring life or magic into the world. And that’s like a similar thing here. Like you can’t, you need the words and the bowl to trap the demon.

Yael: I don’t know so much about the Golem, but there was mention in at least one of the lectures that I listened to about how future iterations of Jewish magic, the Golem, the Dybbuk, things in medieval or early modern times, tended to use magic to sort of do errands for humans. And this, the incantation bowls were very much the opposite. They were, you need to get out of here. And I don’t want you doing anything for me. I want to divorce myself from you. And the reason I say divorce myself from you is because many of the bowls contain language near identical to the deed of Jewish divorce, the get.

Schwab: Yeah. That is so interesting. Yeah.

Yael: Basically what is asked is that the demon Lilith. Lilith is a common trope in these bowls. I don’t know if you know about Lilith. Schwab: Lilith’s like the original, the original demon, right? Like from…

Yael: The original woman demon, Lilith, according to various sources, was Adam’s first wife prior to Eve. And basically what had happened was Lilith, the first wife, had refused to be subservient to Adam in specific ways. Some relate to more adult activities and her unwillingness to do what he wanted in that realm. And then she gets banished from Eden and according to some sources becomes a vampire, a bloodsucker, a child murderer, among other things. And so now she is very much used as an icon of the disobedient or rebellious woman.

And then Eve comes along and she is a much more, you know, I don’t want to necessarily say obedient, but she is a much more mutually beneficial person in Eden.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah. But you were saying the text is similar to a divorce document?

Yael: Yeah, so basically a lot of them say like divorce me from Lilith. There is, I don’t know if it’s a paper or a book written by one of the scholars I mentioned, Professor Bohak. He’s of Tel Aviv University. And it is called Divorcing Lilith. And it speaks about some of these published bowls, many of which contain depictions of Lilith and ask that, you know, Mr. and Mrs. Schwab of 123 Cherry Lane hereby separate themselves by divorce from Lilith. And there are other bowls that refer to Lilith in other contexts. Some of them even say, I want to rid my home of male and female Liliths such that Lilith is now like a Kleenex. Like a Kleenex is all tissues. Lilith is all demons. That’s how ubiquitous she is as a demon.

Schwab: Mm hmm. All demons. There is something very Jewish about like, how everything can be boiled down to some sort of legal contract, you know, like, we like banish this demon, executed through this legal agreement where I want to be very clear on like the terms and conditions, you know, of the banishment of the demon. And there’s just something, I don’t know, like very identifiably Jewish about our like thought out legal approach to banishing demons.

Yael: So it’s interesting that you say that because as I was reading more and more about this, I thought it’s so weird that these demons get treated as logical beings. One of the tropes in the bowls is something that they start with something called historiola, which is basically a narrative proof text.

Schwab: Yeah. Mm-hmm. That’s definitely going on the word list. Mm-hmm.

Yael: Just as Count Dracula was banished from Transylvania in the case of the Schwab’s, so too may the demon be banished from my home. And it’s posited that the reason those historical anecdotes are put at the beginning of the text is because they themselves instill fear in the demons. The demons are like, yeah, I remember that situation and that was bad. Yeah, so I was very confused. said that we’re treating these demons like, you know, not average, like thinking beings.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. How do you as a lawyer feel that we’re making demons out to seem like lawyers?

Yael: I mean, it’s not unheard of, but something that I…

Schwab: We’re not saying that lawyers are demonic, we’re saying demons are legal.

Yael: I don’t have you ever seen the devil in Daniel Webster.

Schwab: No, you have seen so many more things than I have. yeah.

Yael: I think they’re just different. But I was thinking about this and in Professor Manekin-Bamberger’s lecture, she gets to a an excerpt of the Talmud where it talks about how demons are like angels and how demons are like humans. Demons are like angels. in that they can fly and maybe in some other ways, but demons are like humans in that they eat and drink and procreate. And it indicates to us that we treat demons in many ways like we treat humans because we have a lot of overlapping traits. And the demons can react to legal language and they can react to logic.

There is a story somewhere else, I believe, in the Mishnah about a demon who damages someone else’s property and has to pay damages and speaks to one of the people about the damages that are paid and there’s restitution. And someone asked a question at the end of the lecture, like, these demons are law abiding? They’re working out their restitution for certain legal wrongs while still haunting your home or bringing disease to your home. There are some bowls that list disease after disease after disease after disease where the demons names are equated with these diseases.

Another thing with respect to the divorce decree is that the demons are often referred to by more than one name. And as many names as we know of them are listed there, which is a common practice in the get, in the divorce deed. you, when the get is written, the person’s name, I’m not sure if it’s true of the wife’s name, but definitely of the husband’s name. If he is known by any nickname or alias, those names are all written on the divorce document itself. So as not to create any opportunity for someone to go by an alias and ignore what has occurred here.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Right. Which demons would definitely do. If there’s any ambiguity, they’re going to take advantage of that.

Yael: So exactly because they’re demons. One more thing about the demons, probably not the last thing.

Some of the images of the demons have chicken feet. A lot of the images of the demons have chicken feet, actually.

Schwab: I know this from, not from my many years of studying Talmud or Jewish texts, I know this from sleepaway camp where like our counselor would tell us demons, demons, I believe they’re called Shadim in the, like in the Talmud, right? And would be like, oh yeah, it was chicken feet. And then one time as a prank, our counselors like poured, it must’ve been like flour or dirt or sand on the floor and then made chicken feet imprints in it. And they were like, yeah, definitely shadim him came into our bunk at night. And you can tell for sure because it’s chicken feet marks.

Yael: Your counselors were very learned

Schwab: And cruel, but yeah.

Yael: because that was the practice. The practice, if you wanted to know if your house had demons, was to pour dirt on the floor near your bed. And if you woke up in the morning with chicken feet imprinted in the dirt, it wasn’t a sign that maybe chickens lived near your house, that you had chickens. It was a sign that you had demons. So kudos.

Schwab: That you had chickens was a sign of demons. Or that you had like an older brother who was pranking you. Yeah.

Yael: Kudos to your counselor for being very knowledgeable. To get to some of the bowls that were not about banishing demons, there is one that I actually really love that I read about in a 1910 article from the Penn Museum Journal. A lot of the bowls that we have are in the Penn Museum. Penn is a definite center of knowledge for this.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And a professor named James Montgomery, who in 1913 published what I believe is still considered the definitive text on this subject. Before he wrote, he published his book in 1910. He wrote a small article in the Penn Museum journal about a love charm on an incantation bowl where he himself says that the inscriptions are tiresome and that this entire subject is boring.

And it would not be interesting to anyone but a philologist who’s someone who studies languages because he, you know, made a lot of connections between the Syriac and the Mandaic and the Aramaic or a student of religion. So, already interesting to two different groups of people, but he says they’re monotonous and boring. But he says, the museum collection contains two exceptions to this gray monotony and they are unique among all the bowl inscriptions. They spring from the passion which, quote, ”makes the world go round. As love charms, they will arrest the attention of many who have no interest in archaeology.”

Schwab: When academics write interesting things, they go all out. They write really interesting things.

Yael: He is speaking about a bowl that is a charm affected by a woman to gain the love of her husband.

Schwab: Her husband that they’re already married, like not find a husband like they’re already. Okay. Yeah.

Yael: They’re already married, it opens in the name of the Lord of heaven and earth, and then she names her husband and asks that he be inflamed and kindled and burn after her. And her name is then mentioned, and then there is…language about spices, which is interesting because we don’t usually have language about anything going in the bowls. But this seems to be a bowl that accompanies a love potion of some kind. And.

Schwab: So it wasn’t just about the writing on the bowl, but there was like something else also. Yeah. But that also, think like, that this story that you were saying like really emphasizes how this is commissioned by a client. This is not something like a generic one you can just buy.

Yael: In this case, which, exactly. But what Professor Montgomery says is that it’s actually the imagery of fire and burning with respect to passion that indicates that the people who either commissioned or wrote this bowl were influenced by the West. That there was Greco-Latin.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm. Right, so yeah, I see why this would be interesting to like philologists, like what are the metaphors we use for love or for emotions?

Yael: Apparently, at least according to Montgomery, fire is not an image or metaphor that the Jews use for love, but it is something that is very strongly represented in the Greek or the Roman. And so he takes this to be an indication that these, use of these bowls was beyond just the rabbinic Jews or non rabbinic Jews or Syriac Greeks or Mandaeans, but that there was some sort of cultural exchange going on between the East and the West. And he says, I just want to say, he says, the magic herbs are all pungent in character and so symbolize the heat of passion.

So this is the only one of the bowls that he says he finds interesting, even though he goes on to write, you know, the definitive piece of academic work on it, but clearly was a romantic in some way. That is a good example of a non-demonic bowl. There were some bowls that asked for help in business.

There were some bowls that asked for help in making better quality wine. Always a valid endeavor.

Schwab: Important, yeah. You get a good sense of how it is that people are spending their time or what it is that they are worried about or anxious about.

Yael: I think that’s, so I think these are all normal things to be anxious about, business, love, fertility, marriage.

Schwab: Making good wine.

Yael: And I’m glad you mentioned that because I don’t know if I’ve mentioned yet that there were symbols that were discovered without a text that is recognizable to us, that the writing on these bowls is very much believed to be symbol, shapes or symbols. I’ve been envisioning it as like wingdings on Microsoft Word. And the original academic thought was that these were bowls written by con artists or charlatans and sold kind of as knockoffs to unsuspecting people because there were so many illiterate people.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Hmm. interesting. To write to like an illiterate person who can’t read, they don’t know that they’re.

Yael: Yeah, so right, I’m just going to do some doodles on this bowl and unsuspecting Joe Schmo over there is going to pay me money for it. And maybe I’m a believer, maybe I’m not a believer. Maybe if I’m not a believer, I say it doesn’t really matter one way or the other. It’s a harmless con. But as the research has continued over the past century and a half on these bowls, iIt is no longer believed that these were done by charlatans or exclusively done by charlatans. It’s that these shapes may have had meanings that we don’t understand. And the reason why we now think that is because there is significant overlap in the imagery, shapes and drawings between certain of the non-aramaic, non-syriac, non-Mandaic bowls, which I believe have a title themselves, but I can’t remember now what it is. And so those shapes and doodles, those overlapping doodles probably held similar weight to the repeating spells on the legible bowls.

Schwab: Hmm. Like, if it was a con, why would it be the same exact thing every time or similar things? Hmm. Mm-hmm.

Yael: Exactly, exactly, because they don’t seem to have all been written by the same person.

And there’s also an indication that the reason why we thought they were cons at the beginning was this sort of literacy bias that if it’s not in a text that we understand or if it wasn’t used by literate educated people, it probably wasn’t significant or hefty or real.

Schwab: Then it’s nonsense.

Yael: But I think what this is indicating to us, as you mentioned before, is that everyday people were using this, and it meant something to them. And it’s not only the academics and the rabbis whose lives we should be studying and wondering about. So there were people, presumably people who could not read, who were still using these amulets and using them in a meaningful way. And just because we don’t necessarily understand the way in which they’re communicating does not mean that it’s not important.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yeah. Yeah. Which is like, like when we get into those things on the, on this podcast, like there, there is a strong bias towards how we see history, but we can look at other things and consider other ways of looking at history to get a fuller picture. You know, like in your example, if somebody was looking back on the present, they would have their, their picture would not be complete of how people live their lives every single day.

So like how do we pay more attention to things like this that give us a fuller picture of how people were living?

Yael: Especially now when conversations like ours happen in the ether, you know, in the radio waves and on Bluetooth and on the internet and won’t necessarily be preserved in a material way that is discoverable in the future. Maybe it will be because even as we speak, Sesame and ChatGPT and AI and all of these things are really creeping me out and it’s totally possible that someone in the future can just blink and they will be able to see and hear everything I’ve ever said or done. But it is also possible that this is now gone.

Schwab: Right. And only like one object from your entire home will be preserved, and it’s your Demon Incantation Bowl.

Yael: Exactly. Everything will quote unquote be in the cloud. And so because the incantation bowl survived, it must be the most important, even though, you know, really consequential conversations were happening on Zoom or, you know, in blogs and, you know, nothing is going to be printed anymore in the future because we’ve run out of trees and, you know, a variety of things can happen to the materials that we use in everyday life, such that in the future no one will have access to them and therefore they will take what they do have access to and ascribe a tremendous amount of power to it.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. So think about that as you go about your weeks. Think about your own fleeting mortal lives and how almost all evidence of them will barely be present in the future.

Yael: The dust that was removed from the ground when we uncovered these incantation bowls, that’s where you’re headed. You started as dust and you’ll end up as dust and no one will remember anything about you except that you were scared of demons. So there’s a there’s so much here and there’s so much I didn’t get to and I know we’ve run out of time. But hopefully you were able to get a sense of how interesting these bowls are.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

It is incredibly interesting. I kept trying to figure out what is the visual image of the bowl in my head. I think maybe how this episode went of just like this, you know, mix of different texts and we’re circling around and like, as we keep going, we’re led more and more toward the center of what this story is.

Yael:

I hooked you and then I intrapped you and now you’re stuck.

CREDITS

Yael: Jewish History Nerds is a production of Unpacked, an OpenDor Media brand. Subscribe wherever you’re listening to this pod, and follow Unpacked on all the regular social media channels – just search for @UnpackedMedia.

Schwab: And if you’re enjoying nerding out with us, please share this and other episodes with your friends and family! And most of all, please be in touch by writing to us at nerds@unpacked.media. That’s nerds@unpacked.media

Yael: Jewish History Nerds is produced by Jenny Falcon and Rivky Stern. Dr. Henry Abramson is our education lead. It’s edited by Rob Pera.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab.

Yael: And I’m Yael Steiner.

Yael and Schwab: Thanks for listening