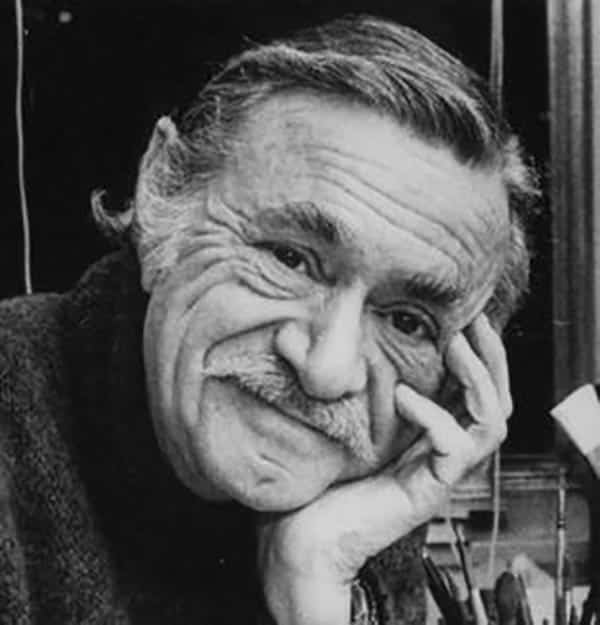

Like so many journeys, this one began with a photograph.

When I was growing up, a framed photograph of Shirley Temple sat on my family’s

Knabe piano. Shirley looks about 10. Her hair is curled into perfect ringlets, her eyes are bright and wide, and her lips are puckered in the adorable faux-surprised look she made famous. She’s perched on the lap of an older man with thinning hair and a full mustache, dressed in a suit and glasses. He looks serious, a bit sad, but in a kindly grandfatherly way.

The photograph is autographed by someone named Morris, clearly the man in the photo, as if he were also famous. “To Barbara,” it read. “Love from Shirley Temple and Uncle Morris.”

Who was this Uncle Morris? And what was he doing with America’s most beloved child actor sitting on his knee, like she wandered into a family portrait?

It turns out that my great-great-uncle was famous. He had invented the Shirley Temple doll and went on to found the Ideal Toy Corporation, one of the most influential toy companies of the 20th century. But his most important invention, the one that started it all, came earlier and from a much humbler place: the teddy bear.

In 1902, he and his wife, Rose, created their first version in the back room of their Brooklyn candy store, stitching together something soft and irresistible that would soon become a staple of childhood.

The story of how Morris Michtom invented a soft little bear made from clothing scraps, stuffed with sawdust, and given button eyes and an expression of sad longing — a certain head-tilted yearning that only the love of a child could assuage — began my doorway into the history of Eastern European Jewish immigrants in the early 20th century and the history of the American toy industry.

As I followed that thread, the story widened. It became not only a tale of one inventive couple, but of a generation: first-generation Jewish immigrants who remade America — and in particular, American childhood — not in their own image but in the image of what they wanted them to be.

Morris and Rose weren’t the only poor immigrants to find their way, make their mark, and ultimately succeed in the U.S. Morris wasn’t even the only Jewish toymaker to follow such a path. It’s astonishing, and not coincidental, how many of the most influential names in American toys belong to Jewish immigrant families: the Hassenfeld brothers, Henry, Hillel, and Herman in Providence; Ruth Mosko and her husband, Elliot Handler, in Los Angeles; and Louis Marx and Joshua Lionel Cowan, in New York City. You may know them better by the toy companies they built: Hasbro, Mattel, Marx, Lionel Trains.

In fact, for much of the 20th century, the American toy industry was largely Jewish, from the company founders and executives to the designers and factory workers, from the wholesale distributors, the army of salesmen, to the retail outlets and the large department stores that sold them.

I began this research thinking I was writing a family memoir, a story of my distant relatives who played an important role in the lives of children for more than a century. But every time I thought I’d found the century of the story, I stumbled across another story to be told, another thread of this rich tapestry to be uncovered. Not just the Michtoms and the Ideal Toy Company, but the Hassenfelds and Hasbro, the Handlers and Mattel, Lionel Cowan, Louis Marx, all the way down to Eddy Goldfarb and his chattering Yakity Yak Talking Teeth, and Lewis Glaser and the plastic model airplanes that dominated my childhood.

Around yet another corner I found the inspirations for many modern toys and, later, action figures: newspaper-strip and comic book characters like Li’l Abner, Popeye, and Joe Palooka created by Jewish immigrants; Jewish-created comic book heroes like Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, and the entire Marvel Universe; even Archie and his Riverdale pals, along with those Classics Illustrated editions that gave kids like me our first taste of CliffNotes.

Open another door, and so many of the best-known children’s authors appeared, from Ezra Jack Keats, Kay Thompson, and Ruth Krauss to Maurice Sendak and the Reys. Yes, Curious George, Peter, Eloise, and Max — all were created by first-generation Jews.

Another turn, and I was suddenly knee-deep in parenting magazines and advice books, and the legions of parenting experts and child psychologists who taught Americans how to raise their children.

For a while, it felt like everywhere I looked, I saw first-generation American Jews — they created an astonishing amount of the toys, games, books, TV shows, and comic books that composed my own childhood. Spanning the entire 20th century, nearly all these men and women had stories similar to Morris’s. For the most part, they were first-generation Americans or, if not, immigrants who came through Ellis Island as young children. Virtually that entire first wave experienced the depravity and deprivation of the slums of the East Coast cities, went to work at an early age, and learned quickly that America could be both a place of unbelievable possibility and a place of familiar prejudice.

And yet, in spite of, and sometimes because of, those struggles, they shared a clear vision for what childhood might be. You can see that vision in the toys they made, the stores they ran, the comics they drew, and the books they wrote. It was a vision that ultimately shaped the future of not just their own children but all children in 20th-century America and beyond.

So I decided not only to tell the bigger story, about all those creators and entrepreneurs and the world they built, but also to ask why: Why them? Why then? Why here?

“Playmakers” is the story of an idealized childhood imagined into existence by people who never got to live it themselves, poor, often Yiddish-speaking, tenement-dwelling children of immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe. They pictured a world in which other children could have the experiences they lacked, and by trying to give that gift to others, they ended up transforming America. They didn’t just change the way we understand childhood. In many ways, they created it.

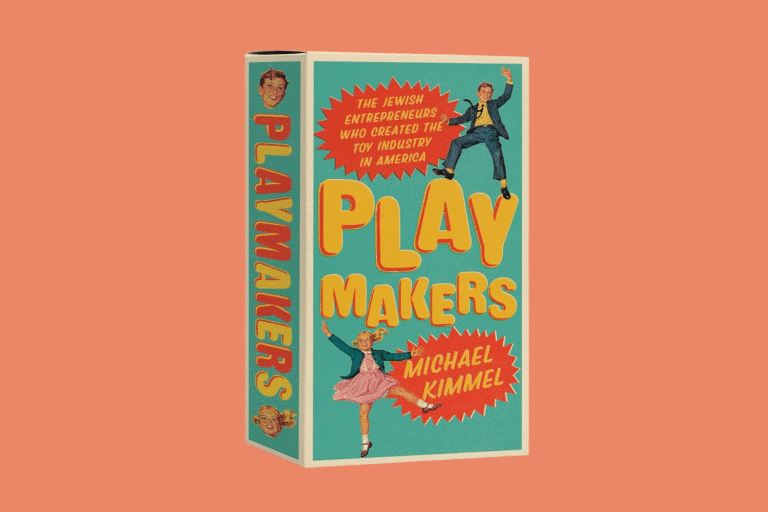

“Playmakers: The Jewish Entrepreneurs Who Created the Toy Industry in America” by Michael Kimmel will be released on February 17, 2026.