The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is one of the most misunderstood clashes in modern history, in part because it’s often told as two separate stories that barely touch. Israelis and Palestinians don’t just disagree about borders or security. They disagree about what happened, what it meant, and what the land represents.

Both peoples describe themselves as indigenous to the same place, but their narratives diverge sharply after that.

For many Israelis, the modern story begins with an exiled people returning to an ancestral homeland and rebuilding sovereignty after centuries of persecution.

For many Palestinians, the modern story begins with outsiders arriving, taking power, and triggering displacement, loss, and an occupation that has shaped daily life for generations.

So what’s the actual history, beyond slogans and social media shortcuts? To answer that, you have to trace how two national movements formed, how empires and borders changed, and how key moments hardened into competing memories that still define the present.

The First Aliyah

Jews and Muslims have both lived in (and passed through) this small stretch of land for centuries. But the modern Israeli-Palestinian conflict began much later, in the late 1800s, when the area that Europeans commonly called “Palestine” was a small province of the Ottoman Empire.

Many Jewish communities had never left the region, and a steady trickle of Jewish migrants arrived over the centuries, drawn by religious attachment to the biblical Land of Israel.

In the 1880s, that trickle became a more noticeable flow as Jews in Eastern Europe fled waves of violent antisemitic attacks known as pogroms. Many left for the United States or Western Europe, but others chose Ottoman Palestine, fueled by a new political idealism: the belief that Jewish safety and dignity required Jewish self-determination.

That idealism became Zionism. One of its most influential early leaders was Theodor Herzl, a journalist who concluded that entrenched antisemitism in Europe was not a temporary fever but a permanent condition. Inspired by the era’s nationalist movements, Herzl argued that Jews needed a state of their own, and he and his supporters increasingly focused on Palestine, the site of the ancient Jewish homeland.

As Zionist immigration grew, so did anxiety and resentment among the local Arab population, who saw rapid demographic and political change in a land they already considered home. Even when Jewish immigrants purchased land legally, the broader project could still feel, to many Arabs, like a colonialist movement arriving with foreign backing and ambitions that threatened their future. Competing national aspirations began to form on the same ground.

After World War I, the conflict hardened. The Ottoman Empire collapsed, and Britain took control under a League of Nations mandate, creating “Mandatory Palestine.”

Across the region, Arab leaders debated what independence should look like, whether as a larger pan-Arab political unit that would include Ottoman Palestine or as separate states drawn along new imperial borders. In Mandatory Palestine, many Arabs increasingly rallied around a distinct Palestinian nationalism, opposing both British rule and the Zionist project.

Politics wasn’t the only fuel. Some opponents framed Jewish immigration and sovereignty in religious terms, too, arguing that a land long ruled by Muslims should not pass into non-Muslim political control.

By the early 20th century, Jews and Arabs were no longer just neighbors with competing interests. They were two emerging national movements, each convinced the land was central to its identity, headed toward a collision that would define the century.

Violence erupts

Two events in the late 1920s and 1930s proved especially pivotal, both as warning shots and as accelerants to the long and bloody conflict to come.

The first was the violence of 1929, when unrest over access and control around Jerusalem’s holy sites, especially the area of the Western Wall, spiraled into riots across Mandatory Palestine, including the massacre of Jews in Hebron. In the run-up, a propaganda campaign spread claiming Jews intended to seize or desecrate Muslim holy places and rebuild the Jewish temple, a charge that helped inflame crowds and turn political tension into lethal violence.

The second was the 1936–1939 Arab Revolt, a three-year uprising directed at British rule and the growing Zionist project. Britain ultimately crushed the revolt using mass arrests, expulsions, executions, and harsh counterinsurgency tactics It did so in part through cooperation with Jewish forces such as the Jewish Settlement Police and the British-Jewish Special Night Squads. The suppression weakened segments of Palestinian Arab political and military leadership at a crucial moment.

Yet the revolt also pushed British policy in a decisive direction. In 1939, Britain issued the White Paper, sharply limiting Jewish immigration to 75,000 over five years and restricting land purchases, with future immigration tied to Arab consent. For the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, it felt like betrayal, especially as they had helped the Brits quash the Arab rebellion. Simultaneously, the Nazi threat intensified, and European Jews were increasingly desperate for escape routes.

That fury helped shift the conflict’s target. Tensions between the Jewish community and Britain rose dramatically after 1939, and armed underground groups would later launch an insurgency against British rule, seeing the mandate as an obstacle to both sovereignty and rescue

But it wasn’t enough to save European Jewry. Six million Jews, one-third of the world’s Jewish population, were murdered in the horrors of the Holocaust by Nazi Germany and its collaborators.

In the aftermath, as survivors emerged from the ruins and the scale of the atrocities became undeniable, support for a Jewish state hardened into something more than ideology for many Jews worldwide: a perceived necessity for refuge and self-defense in a world that had stood silently and watched Europe’s Jewish community disappear.

A Jewish state probably wouldn’t have prevented the atrocities, but it might have minimized the deadly toll.

The Partition Plan

After World War II, Britain was spent, politically and financially, and increasingly unwilling to keep refereeing a conflict it could not resolve. So, London turned the question of Mandate Palestine over to the newly formed United Nations.

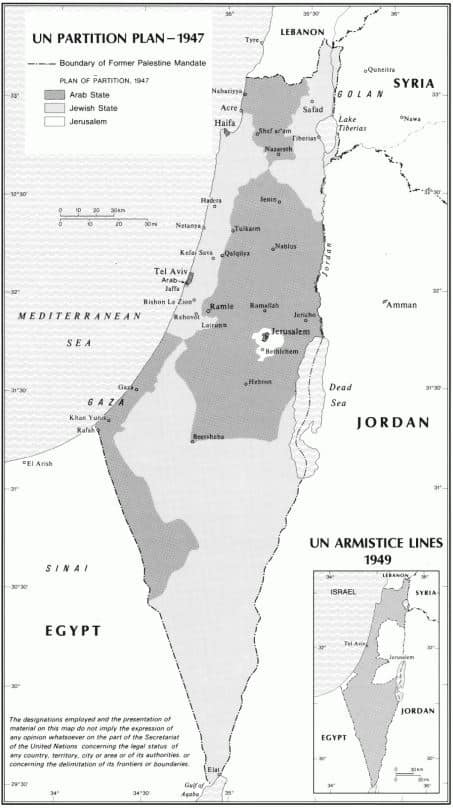

On November 29, 1947, the U.N. General Assembly approved Resolution 181, recommending that the British Mandate be partitioned into two independent states, one Jewish and one Arab, with economic links between them.

Because Jerusalem mattered to Jews, Muslims, and Christians alike, the plan proposed a special international regime for the city: demilitarized, administered by the UN, and set to remain in place for an initial 10-year period, after which residents could express their wishes in a referendum.

Jewish leaders largely accepted the plan as an imperfect but historic opening. Arab leaders rejected it, arguing that the UN had no right to partition a land they understood as theirs, and some warned it would mean war, including rhetoric about a “war of extermination.”

Violence broke out almost immediately. The U.N. vote triggered a civil war between Jewish and Arab communities in Mandatory Palestine, while the British, already on their way out, largely stood aside.

On May 14, 1948, hours before the mandate formally ended, Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion proclaimed the establishment of the State of Israel. The next day, armies from Egypt, Transjordan (Jordan), Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon invaded the former mandate territory, seeking to defeat the new state and block the partition outcome by force.

The fighting was bitter and costly. The Jews were outmanned, but they had one thing the Arabs didn’t: unity. After a year of bitter fighting, the Jewish state had repelled the Arab armies, establishing a fragile truce.

By war’s end, 6,373 Israelis had been killed, nearly 1% of the Jewish community at the time. Estimates for Palestinian Arab deaths vary widely, with some major reference works placing them in the 10,000 to 15,000 range.

Despite the toll, Israel’s War of Independence was a huge victory for the tiny Jewish state. When the guns finally quieted into armistice agreements in 1949, the map no longer matched the UN’s blueprint. Israel controlled about 78% of the former mandate territory, more than the partition plan had allotted. Jerusalem, intended to be internationalized, ended up divided in practice: East Jerusalem (and the West Bank) came under Jordanian rule, while Israel held the western part of the city. The Gaza Strip came under Egyptian control.

Independence or Catastrophe?

Here is where the narratives of the conflict truly split.

For Palestinians, the outcome of the 1947 to 1949 war is remembered as the Nakba, Arabic for “catastrophe.” Roughly 700,000 Palestinians became refugees, some fleeing combat and fear, others driven out in expulsions that historians still debate in detail. Thousands died, and hundreds of Arab towns and villages were depopulated and destroyed, a physical erasure that turned displacement into something you could point to on a map.

Those refugees scattered. Some went to neighboring Arab countries, but most ended up in the West Bank and Gaza, the areas envisioned for an Arab state in the UN plan, which, after the war, fell under Jordanian and Egyptian control. A smaller number of Palestinians remained inside Israel’s borders. They received Israeli citizenship, but lived under a military administration for years, with movement and daily life heavily restricted until that system was dismantled in 1966.

The next two decades never delivered a real ending, only armistice lines and mounting pressure. Arab countries tried to squeeze Israel by cutting off its access to fuel and water. Across Israel’s borders, Palestinian guerrilla attacks, often described as fedayeen raids, and Israeli reprisals helped keep the conflict hot even when the front lines looked quiet on paper.

Then, in June 1967, the simmering crisis boiled over. After a period of escalating tensions and military mobilization, Israel launched preemptive air strikes that crippled Egypt’s air force, and the war that followed reshaped the region in less than a week.

Within six days, Israel had defeated the Arab armies and captured East Jerusalem, the West Bank, Gaza, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights.

That victory came with a seismic consequence: Israel now controlled territories home to 1.2 million Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza alone, including many refugees from 1948. The world immediately faced a new question that has never stopped echoing: were these lands bargaining chips, permanent conquests, or occupied territory that would have to be traded away for peace?

The U.N. tried to codify a way out with Security Council Resolution 242, linking Israeli withdrawal from territories captured in 1967 to the end of belligerency and recognition of every state’s right to live in peace within secure boundaries. But in September 1967, Arab leaders meeting in Khartoum issued what became known as the “Three Nos”: no peace, no recognition, and no negotiations with Israel. For the next decade, that stance would shape the region’s diplomatic horizon, keeping the conflict trapped between unresolved war and impossible peace.

Israel’s leaders also had little incentive to hand back territory they now saw as strategic depth. Before 1967, the country’s “waist” near the Mediterranean was only about 9 miles wide at its narrowest point, a geography that many Israelis viewed as militarily precarious.

The Settlement Movement

In the years after the Six-Day War, Israel began establishing Jewish civilian communities in the West Bank, later known as settlements. Early on, Israeli governments often framed them in security terms, as a way to create buffers and early-warning presence, especially in areas seen as strategically vital. For many Israelis, though, the project was not only about defense. It was also about history and religion, a return to places tied to Jewish memory and the Bible.

For Palestinians, those same settlements, along with Israel’s military rule in the West Bank, looked like a continuing seizure of land and the entrenchment of occupation, making a future Palestinian state feel more distant, not closer.

That sense of injustice helped intensify a new phase of Palestinian politics. Disparate guerrilla factions increasingly rallied around the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), founded in 1964, and then around Yasser Arafat, who became its leader in 1969. In its 1968 National Charter, the PLO defined armed struggle as central to its strategy for liberating Palestine, a posture many Israelis understood as existential, because it did not accept Israel as a legitimate, permanent neighbor, and vowed to work until the Jewish state did not exist.

Meanwhile, anger over 1967 simmered in neighboring Arab states, especially Egypt and Syria. Israel did not believe they would risk another major war so soon after their defeat. But on October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a coordinated surprise attack on Israel during Yom Kippur, catching the country off guard and inflicting heavy losses. Israel ultimately survived and pushed back, but this victory ultimately felt more like a defeat.

Paradoxically, that trauma opened a diplomatic door. Within a few years, Egypt and Israel shifted from frozen hostility to negotiations, culminating in the Camp David Accords (September 1978) and then a formal peace treaty signed at the White House on March 26, 1979.

This was a turning point: the broader Arab-Israeli conflict began, slowly, to narrow into a more concentrated Israeli-Palestinian struggle. Many Palestinians felt Egypt had made peace without them, and that if regional armies were not going to “solve” their cause, Palestinians would have to force the issue themselves. The PLO and other groups escalated attacks, including attacks on civilians, intended to pressure Israel politically. But instead of loosening Israel’s defenses, the violence largely hardened them, reshaping Israeli public opinion and deepening the cycle of retaliation and control.

The First Intifada

In the late 1970s, Israel began expanding settlement-building in the West Bank much more aggressively, especially after 1977. Some of that push was framed in security terms, and some of it was driven by ideology, with plans designed to place Israeli communities along key ridgelines and around Palestinian population centers, shaping the map in ways that would make a contiguous Palestinian state harder to draw.

The pressure finally burst into the First Intifada in late 1987, a mass uprising that mixed civil resistance with violence and was met with sweeping arrests, curfews, and heavy use of force. By the time the Oslo process began in 1993, Israeli civilians and security personnel killed by Palestinians totaled about 160, while Palestinians killed by Israeli security forces and civilians totaled well over 1,100.

The Intifada also changed who was leading the Palestinian struggle. Hamas emerged during this period as an Islamist movement that explicitly rejected coexistence with Israel, with its early doctrine casting the conflict in religious terms and envisioning an Islamic political order across all of Palestine.

At the same time, the PLO, still the dominant address for Palestinian national politics, moved in a more pragmatic direction. In 1993 and 1995, Israel and the PLO signed the Oslo Accords, exchanging mutual recognition and laying out a phased process meant to culminate in permanent-status negotiations. One of Oslo’s immediate outcomes was the creation of the Palestinian Authority, which assumed governing responsibilities in parts of the West Bank and Gaza during an interim period.

And the regional picture seemed to be shifting, too. In 1994, Israel and Jordan formalized peace, ending the state of war between them.

For a moment, after decades of war and retaliation, it looked like the conflict might be moving from battlefields to bargaining tables, with real borders, real autonomy, and real normalization no longer sounding like fantasy.

The Questions Left Unanswered by Oslo

But Oslo left the hardest questions deliberately unresolved.

One of the most explosive issues was the fate of Palestinian refugees displaced in 1948 and 1967. Palestinians pressed Israel to accept the principle of a “right of return,” often rooted in U.N. General Assembly Resolution 194’s language about allowing refugees who wish to return and “live at peace” to do so, and compensating those who do not. By the mid-1990s, UNRWA’s rolls listed just over 3 million registered Palestinian refugees across the region, reflecting how refugee status had extended across generations.

Israel rejected a broad right of return into Israel proper, arguing that it would function as a demographic end-run around the idea of a Jewish-majority state. That fear wasn’t abstract: Israel’s population in the early 1990s was a little over 5.3 million, with Arabs making up about one-fifth of citizens, meaning that a large-scale influx would dramatically change the country’s internal balance.

Instead, Oslo tried to buy time. The 1993 Declaration of Principles set a five-year interim period and postponed “permanent status” issues, explicitly naming Jerusalem, refugees, settlements, borders, and security as questions to be negotiated later.

The trouble was that the process was being attacked from both ends. Hamas carried out deadly attacks aimed at convincing Israelis that “peace” meant vulnerability, not security. On the Israeli side, extremists also acted violently. The most seismic blow came on November 4, 1995, when Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish extremist opposed to Oslo. The negotiations survived on paper, but politically, they began to hemorrhage.

In a last-ditch effort to revive the process, U.S. President Bill Clinton brought the parties to Camp David in July 2000. Israel agreed to a demilitarized Palestinian state in all of Gaza and 95% of the West Bank, with land swaps, and limits tied to security arrangements. Arafat did not accept the terms or provide a counterproposal, and the summit ended without an agreement. Refugees and Jerusalem remained the core sticking points, and the collapse of Camp David helped convince many people on both sides that Oslo’s promise was slipping out of reach.

Then the ground gave way. Beginning in late September 2000, the Second Intifada brought a brutal cycle of suicide bombings, shootings, raids, and reprisals. By early 2005, about 1,000 Israelis had been killed. Israel struck back in deadly counter-terror operations, resulting in as many as four thousand Palestinian fatalities. The “peace process” didn’t just stall; It was buried under the mathematics of grief.

The Second Intifada

The Second Intifada drastically altered reality for both Israelis and Palestinians. The Israeli left had been some of the fiercest advocates for peace with the Palestinians. Now, it was disillusioned and politically weakened.

And Palestinians faced a bleak future. Israel moved to prevent attacks from the West Bank by building a security barrier and tightening the permit and checkpoint system. Israeli officials and some analysts credit the barrier, alongside other counterterror measures, with sharply reducing successful infiltrations from areas where it was completed.

But the barrier’s route and the day-to-day reality around crossings also made ordinary life far harder for many Palestinians, especially workers, students, and families whose routines depended on movement between towns, Jerusalem, and Israel. Many were sometimes forced to wait for hours to cross into Israel, where they had jobs and extended families. Sometimes they were denied entry into Israel altogether.

In that atmosphere, the two-state solution, once a plausible destination, began to feel like a slogan people repeated out of habit rather than belief.

Gaza, however, looked different to Israeli policymakers. By the mid-2000s, roughly 1.4 million Palestinians lived in the Strip, alongside about 8,000 to 9,000 Israeli settlers concentrated in a small number of settlements, protected by the Israeli army at a high cost and to much international scrutiny.

In August to September 2005, Israel carried out a unilateral disengagement, evacuating settlers and withdrawing its permanent military presence from Gaza. The move split Israeli society, and it did not create true independence for Gaza overnight. The Strip remained heavily dependent on access through border crossings, with movement of people and goods shaped by policies enforced by both Israel and Egypt.

The Palestinians also couldn’t agree among themselves on who would be in charge. Hamas won a majority in the Palestinian legislative elections in 2006, but its infighting with rival group Fatah made governing impossible. In 2007, Hamas took control of the Strip by force, leaving the Palestinian Authority dominant in parts of the West Bank.

From there, Gaza became a launchpad and a bunker at the same time. Over the years that followed, Hamas and other armed groups repeatedly fired rockets and mortars into Israel, prompting air-raid sirens and regular escalations. Hamas also invested heavily in an extensive tunnel system designed to shield fighters and weapons from surveillance and strikes. Israel’s air campaigns and periodic ground operations damaged Hamas’s capabilities, sometimes for months, sometimes for weeks, but the basic political reality held: Hamas’s grip on Gaza remained firm.

Meanwhile, the West Bank stayed combustible. The security barrier and tighter controls helped reduce successful attacks inside Israel, but they did not end violence, especially in and around the West Bank, where Israelis and Palestinians live in close proximity.

In the years that followed, Israelis continued to be killed and injured in shootings, stabbings, and other attacks linked to the West Bank, while Palestinians faced raids, arrests, and military operations that became a grim rhythm of the post-Intifada era. For the Palestinians, these terror attacks paid, literally. The Palestinian Authority provided lifetime payments to the families of militants, financially incentivizing them to target Israelis.

Israel, for its part, continued deepening its footprint in the West Bank by expanding settlements and authorizing new communities, arguing that the territory is disputed and that Jewish ties to the land are historic. Much of the international community disagrees.

Palestinians also faced another, worsening threat: violence from Israeli settlers and far-right extremists.

But while Israelis and Palestinians lived in an uneasy status quo, cycling between mini-wars and terror attacks and settlement construction, Israel’s relationship with the wider Arab world was improving. In 2020, Israel normalized relations with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain through the Abraham Accords, and related normalization steps followed with Morocco and Sudan.

For a moment, it even looked like Saudi Arabia might join. U.S.-backed talks over a possible Saudi-Israel normalization deal were widely reported in 2023.

But events were about to unfold that would shake Israel, and indeed all of the Middle East.

The October 7 attacks

That shake-up arrived at dawn on Oct. 7, 2023, when Hamas-led fighters breached Israel’s Gaza border in a coordinated assault by land, air, and sea. Israeli authorities say about 1,200 people were killed, most of them civilians, and 251 hostages were taken into Gaza in what became the bloodiest day in Jewish history since the Holocaust. More Israeli lives were lost in a few hours than in the entire five years of the Second Intifada.

Israeli communities near the border were overwhelmed; attackers moved house to house in multiple towns and kibbutzim, struck military bases, and attacked a large music festival where many people were killed while trying to flee.

In Hamas-controlled Gaza and the Palestinian Authority-controlled West Bank, the onslaught was met with cheering and celebration. The leadership of Fatah, the political organization dominating the Palestinian Authority, praised the attacks as “self-defense” and the attackers as heroes who were a “source of pride and honor” for the Palestinian people.

Israel responded with a massive air campaign and a ground war aimed at dismantling Hamas’s military and governing capabilities and securing the return of hostages. The cost has been staggering on both sides. Hundreds of Israeli soldiers went into Gaza only to return in body bags. Tens of thousands of Palestinians have reportedly been killed, though Israel claims that nearly half of the fatalities were Hamas terror operatives.

The humanitarian impact inside Gaza has been catastrophic: nearly all of Gaza’s 2.3 million residents have been displaced at least once, with large parts of the population crowded into a shrinking area of the Strip amid shortages of food, water, shelter, and medical care.

This is where the conflict’s dueling narratives harden into something close to concrete. For Israelis and Jews around the world, October 7 revived deep fears shaped by centuries of persecution and the memory of the Holocaust. For some, it reinforced the pattern that ceding any territory to the Palestinians endangers Israel, and that Palestinian independence will cause further danger.

For Palestinians and their supporters, the scale of destruction in Gaza has become the defining reality, proof that life without sovereignty can collapse into mass suffering overnight. They see the war as a mass extermination attempt. And even though some Palestinians do blame Hamas for the chain reaction that followed October 7, many more blame Israel for the carnage.

That leaves Israelis and Palestinians facing the same grim question from opposite sides of the shattered glass: what does safety look like, what does freedom look like, and is there any political shape that can hold both at once? Any lasting peace will require more than maps and treaties. It will require each side to recognize not only its own trauma but the other’s as well, without turning recognition into surrender.